It had been a relatively mild summer. The odd storm offered some respite from the unbearable heat and choking pollution, and by mid-May there were signs of the imminent monsoon season. Reports from the Meteorological Department assured us that we would have a healthy amount of rain this year, and that the droughts of 2015-16 was a thing of the — temporary — past.

Many of us went to bed on the 18th of May happily surprised to be woken up by the sounds of torrential rains in the middle of the night. By 7am, however, the honeymoon with the monsoon was over for some as numerous areas in the city were up to a metre deep in water. As authorities rushed around setting up pumps and building sandbag banks, social media led the blame game, with digital fingers pointing at an assortment of targets. It was to take around 24 hours for the city to be drained of its excess water and for authorities to begin to explain how they were caught so unaware. Since then there has been fear of another flood; many of us remembering the great damage caused in 2005 when the water spilled out of the Ping River causing around 5 billion baht in damage to the local economy.

“The May 19th flood,” said Pairin Limcharoen, Head of the Branch Office of the Department of Disaster Prevention and Mitigation in the Northern Province, “was an aberration. On an average year we get around 1200-1300 mm of rainfall, though the past two years were far below average with a rainfall of only around 7-800mm. But between 1-4am of the 19th of May, we had nearly 130mm of rainfall, ten percent of a seasonal average! It was quite remarkable. Combine that with the rain that had fallen the night before and the fact that the majority of rain fell on Doi Suthep-Pui National Park to the west of the city, it meant that a massive amount of water came down the mountains straight into the university side of the city in a very short amount of time. The floods of the past have generally been caused by the Ping River overflowing; this had nothing to do with the Ping which was actually at only 1 metre deep. When it reaches 4 metres in depth, that is the critical level. So the Ping was completely irrelevant to this flood.”

Ancient Foresight

When King Mengrai first had the idea to build a city in the Chiang Mai valley in the late 13th century, he didn’t pick Chiang Mai for its location, instead building Vieng Kum Kam around three kilometres to the south east of Chiang Mai. However, repeated flooding led him to rethink his capital and ten years later, in 1296, Chiang Mai was founded as the capital city of his domain.

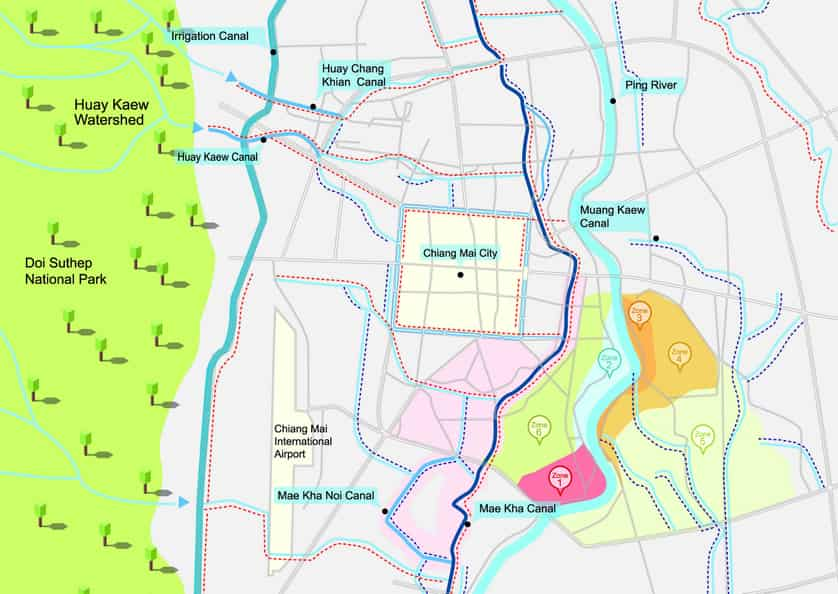

“Following his failed attempt at a city at Vieng Kum Kam, Mengrai really focused on natural waterways as a strategy when designing his new city,” said Assist. Prof. Wasan Jompakdee of the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Chiang Mai University, who has also been instrumental in spearheading the cleaning of Mae Kha as well as many other ancient city canals. “To the west of the city lies the Suthep Mountains, a natural buffer against warring parties. As rain fell on the mountains and water poured into the city, they formed the Huay Kaew, Chang Khian and other such streams which eventually joined the Mae Kha River which ran parallel to the Ping River, both flowing from north to south. Water coming down from the mountains on the north side of the city would flow straight into Mae Kha Luang and water on the south of the city would flow into the smaller Mae Kha Noi, both of which would eventually join the Ping River south of the city in Hang Dong District. The one square mile walled moat was built to absorb any other excess water flowing down from the mountains and there was also a large swamp type lake at the north east corner of the moat which was a water source for animals in the summer and another means of managing excess water during the rainy months.”

“It was superb city planning,” explained Wasan. “You have the Ping River to the east, a major artery for transport, trade and agriculture. Should the Ping flood, as it often did, then the city was protected by the smaller Mae Kha River which was flanked by an outer wall, remains of which can still be seen today near the Night Bazaar along Kampaengdin Road. The Mae Kha was therefore a natural outer moat, if you will, and there were also other natural waterways which circled the moat, offering layers and layers of protection against floods. The flood plains between the two rivers was terrific for agriculture and its relatively short distance from the city centre made this an important food basket for the entire city. The city’s craftspeople and traders lived outside the old moat — the silversmith community of Wualai, and rattan weavers of Chang Moi, for instance — but inside the outer wall, while the royalty and gentry inside the moat had the best protection of all with the moated wall. So you can see how brilliantly thought out the city plan was. All we have to do is leave it to gravity and nature, they provide their own solutions. So it is so frustrating to see that we are having these city floods when we shouldn’t.”

“In the old days when there was flash floods, it was readily absorbed into the earth,” continued Wasan. “Apart from the historical flooding of the Ping River, which new dredging and water management systems is doing a good job at mitigating, the real problems began about half a century ago as Chiang Mai began to develop. City planners completely ignored old waterways. Mahidol Road was built bang smack across the Mae Kha Luang and Mae Kha Noi Canals, blocking any release of water from the south of the city, which also happens to be the lowest area of the city as well. This is why the Haiya and Wualai communities are always the first and worst to flood. Instead of building roadways in parallel to waterways, or at least building channels for absorption, waterways were completely blocked off. With over development and concreting of the ground, natural absorption has also been affected. Unlike Bangkok where ground water is only a few metres deep, Chiang Mai has the ability to absorb a lot of water — look at how deep we have to dig for well water. The problem isn’t just the cementing of urbanisation, but also the fact that we don’t filter our water, so instead of just plain water being absorbed, it gets blocked by fat and oils and as we have seen this year, waste.”

“The area of the Mae Kha basin is around 100 squared kilometres, three times the size of the municipality,” continued Wasan. “If we can manage this sub watershed, it would be a huge win for the city. The problem doesn’t just lie with bad city planning and rampant urbanisation, it is also with how we citizens of Chiang Mai have been mistreating our historical waterways.”

Waste Deep

We have all been aghast over the past month with reports and images from efforts being made to clean up the city’s water ways. Entire refrigerators, piles of mattresses, hundreds of beer bottles, even sofas and televisions have been dredged out of the Mae Kha in recent weeks. Pictures show even the municipal authorities looking rather startled as they toured efforts to clean the canals, watching as tonnes of water hyacinth were removed from areas downstream from sluices and vile amounts of grease and fat scooped out of drains.

“Over the past two years of drought we have had a very active working committee, led by the governor, pooling resources and setting up communication channels between all the related organisations,” explained Apiwat Poomthaisong, Director of Operations and Maintenance Division at the Regional Irrigation Department. “Our office manages regional water resources, but because of our 800 personnel and superior resources to other organisations, we are always on hand to assist with any problems in the city. Interestingly enough on the 16th of May the governor had called our working group together and told us to start cleaning out waterways in anticipation of flooding. He also warned us to all be alert. In spite of the 24 hours of flooding three days later, I think that our new One Map plan and strategy formed last year in anticipation of this year’s flooding, which divides the most vulnerable areas of the city into six tightly managed zones, really worked.”

The One Map plan is touted by all involved to be an excellent master plan for dealing with all future flood problems, with each person tasked with clear points of responsibility, a good communication system for shared resources, weekly, daily and hourly reports and updates from dams, sluices and rivers on water levels, the Meteorological Department and other sources of data as well as providing a clear strategy that allows all parties to work off the same master plan.

As rain began to fall in the early hours of the 19th May, the Line group which has around 60 active members, including the governor’s and mayor’s offices, the Irrigation Department, the Provincial Administrative Organisation, the Marine Department, various district and sub-district groups, community leaders, activists, army Circle 33, the 5th Region Police, researchers and emergency crew were all alerted to the coming flood. By 4am dozens of pumps were in place, pushing water out of the city centre and by 7am the governor was holding an emergency meeting. It took twelve hours for the water to be reduced by 95% and another twelve to drain the remaining shallow areas, or ‘woks’, in the city. By the evening of the 20th of May the fire department had cleaned up all the detritus from the roads and there were few signs of the flood that left many houses and businesses in some communities debilitated. A job well done, said all authorities interviewed by Citylife, patting themselves on the back.

Mae Kha Funk

The Mae Kha Canal, so integral to King Mengrai’s city planning is more often smelt than seen. For decades mayors have given lip service to cleaning it up and activists and the media have rallied around intermittent efforts to get the job done. “The problem lies in that the Mae Kha basin isn’t just made up of one or two major arteries, but a complex, interconnected, and often forgotten network of streams and ponds meandering through the eastern and southern parts of the city,” explained Wasan, pointing to a giant map of Chiang Mai featuring a surprising number of waterways.

“While waterways’ shoulders are by law public,” continued Wasan, “and the common Lanna law dictates that an oxcart’s width be left alongside all banks of rivers and streams for public use, much of the Mae Kha’s banks are crowded with houses and shacks where the poorest people in our city live. It is hard to evict them when they have nowhere to go.” In the past 30 years, claims Wasan, around 90% of squatters have been evicted from the banks of the Mae Kha, thanks to the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security which recently offered compensation to 2,000 families. Unfortunately many simply moved to flank other waterways in the city, and there is no universal plan for compensation, so congestion remains.

“We actually invited some of the old residents of the city to take us around recently to show us forgotten waterways,” said Secretary to the Mayor Assanee Buranupakorn. “It was fascinating to see some streams simply disappearing into people’s houses. There are 100 communities within the municipality area and we have very good communication with all of them, but we are not heartless, we can’t just go in and start kicking people out of their homes,” especially, one presumes, since these are the communities voting in mayoral elections.

“I am banging the gong to announce that it is time,” declared Wasan about the formation of the Committee to Develop and Solve Problems of The Mae Kha Canal, which he formed in 2014. “I believe that if we work together we can solve this problem in ten years. We will need to plant more trees in the mountains and protect our water sources, we need to dredge and maintain the flow of the canals, relocate squatters, educate people as to how to manage their waste, launch a campaign against littering, and make sure that there is always a budget and people responsible of maintaining the waterways.”

Earlier this year Mayor Tassanai Buranupakorn announced that the municipality would set a 50 million baht budget to clean out the Mae Kha with the aim of featuring it in the upcoming proposal to propel Chiang Mai towards UNESCO World Heritage status. But according to his secretary Assanee, he knew of no such budget and said that the priority was to solve current problems.

Swirling Rumours and Misconceptions

Within hours of the 19th May flood, social media was abuzz with speculation that the flood was avoidable, and that the municipality allowed it to happen because of the limited flood budget over the past two years of drought. Some media outlets speculated that only a flood could increase the annual budget with implications that it was a game of corruption. “That is absolutely false,” countered Assanee. “We don’t receive any budget from the central government for flooding, so I want to say that that is categorically untrue. We use our own budget for these issues and we manage it tightly.” He went on to say that the municipality has 100 full time staff allocated to flooding related issues, their salaries comprising the majority of the annual budget, and that this year alone they have distributed 145,000 sandbags to city communities.

Apiwat from the Irrigation Department also complained about rumours that his department was releasing water from the Mae Ngad and Mae Guang dams, causing flooding downstream. “That is completely false. We have not released any water at all from the dams, why would we? Right now Mae Ngad is at 33% capacity and Mae Guang at 16%, our medium sized reservoirs are at between 30-90%, even if we collect all the projected rainfall this year neither dams will overflow – Mae Ngad will likely reach 95% and Mae Guang 60% by the end of the rains. We even have live CCTV at both dams which is available for public viewing as evidence. So we have no reason at all to release any water from the dams; they are being tightly managed and we don’t expect any flooding from the Ping River this year.”

“We are going to be working very hard cleaning out all the waterways and increasing flow,” added Assanee. “But I plead the public to please stop throwing waste down the drains and in rivers. If you need to get rid of large items, call our office, we will come and remove it for you for free. Also there is always a complaint that there are not enough waste bins in Chiang Mai. But the problem is no one seems to want one outside their homes. Often we will put a bin somewhere and find it has simply been thrown or moved away…then they complain about garbage.”

Flowing and Fragrant Future

“I am beginning to see the awakening and activity by management levels in the municipality,” ended Wasan, with some hope. “In the past, we haven’t given focus and importance to systems of water. We would just build dams and fix hot spots, ignoring the natural and entire ecosystem and waterways. Lakes, ponds and streams were covered by cement. These are our natural drainage system! So with our new Mae Kha group, we hope to bring back a sense of history, community and pride as well as to solve many of our city’s problems.”