I arrived at the Children’s Advocacy Center Thailand (ACT Center), Chiang Mai’s new strategy to address human trafficking, formally opened in February 2016, on a sunny Thursday afternoon. Despite the serious and urgent reasons for the centre’s existence, upon entering the back yard filled with luscious green plants, a basketball court, and a trampoline, then being greeted by friendly volunteers, I found myself instantly feeling welcomed and at ease. This emotional response is exactly what ACT Center wants for at-risk children with whom they interact. The goal of ACT Center is to prevent at-risk children from becoming trafficked and to help those who have been trafficked through the judicial process and emotional recovery.

Human Trafficking in Thailand

The United Nations defines trafficking as the “recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation.” Thailand is unique in that it “is a source, destination, and transit country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking” (US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report 2015). Also, Thailand’s trafficking problem is world renown; the US Department of State Trafficking in Persons Report (TIP Report) downgraded Thailand to Tier 3 in 2014, after spending three years on the Tier 2 watch list. Tier 3 is the lowest of ratings a country can receive. This means that, “the American government ranks Thailand among the least effective of all countries in fighting trafficking, along with Iran, North Korea and Syria” (The Economist).

Trafficking is found throughout at-risk populations that commonly include migrants, sex workers, and street children. In the spring of 2015, The Economist reported, “Thailand’s fishing industry is rife with trafficking and abuse.” This trafficking, which typically attacks migrants, along with sex trafficking of children and adults makes up a large proportion of human trafficking in Thailand.

During the summer of 2015, mass graves were found at Rohingya human trafficking camps along the Thai-Malaysian border. After finding these graves, the Thai government made multiple arrests, including the arrests of high-ranking officials, but the judicial process has yet to be completed. “They’ve indicted people, but they haven’t had a successful trial and punishment of any of them,” said Ben Svasti founder of FOCUS, formerly known as TRAFCORD, an organisation focusing on human trafficking, who also holds the position of Honorary British Consul here in Chiang Mai.

This lack of completion might make it challenging for Thailand to rise from Tier 3 when the 2016 TIP Report is released in June. Recently, he said, the government has taken significant action against trafficking and the establishment of the ACT Center may help improve the status.

The centre mainly works with child victims of sex trafficking, although it is possible that this model could be expanded to work with other types of trafficking victims.

Before the ACT

In 2014, the same year that Thailand was downgraded to Tier 3 by the US Trafficking in Persons Report, the Vice Governor of Chiang Mai, Charoenrit Sanguansat, acting on behalf of the Governor in his capacity as Chairman of the Provincial Centre for Prevention & Suppression of Human Trafficking, met with Svasti and Police Colonel Apichart Hattasin, better known as Dao, in order to come up with a new strategy for addressing human trafficking. “Dao is probably the policeman with the most experience in this area and FOCUS/TRAFCORD is the NGO with the longest experience in it,” Svasti explained why the Vice Governor came to them.

“The Vice Governor said okay, looking at the review of human trafficking, we still have a problem, after 12 years we still have a problem, what are we doing right? What are we doing wrong? Dao and myself said it’s time for a new model for human trafficking. We must change the emphasis of what we’ve been doing because it doesn’t work. We must try a new model,” Svasti said.

So the Deputy Governor put his trust in Dao and Svasti and asked them to come up with this new model, a tall order indeed.

“We looked at what works and what doesn’t work. We quickly saw there was one project that worked quite well, the HUG Project, [a Chiang Mai based NGO predominantly involved in the prevention of trafficking]. They were working with street children, bonding with them, providing advice and fun activities. Having bonded, they were then getting to learn about a lot of issues — child abuse, and human trafficking, and forced prostitution. Once the community trusted the staff and volunteers at HUG, they began to get reports. So we thought this is good because at the moment none of the high risk groups are reporting to the government,” Svasti explained.

“We also looked into American models. Because both myself and Dao have taken part in the US International Visitor Leadership Program…and we were taken to see projects which you could call community policing, where the police get close to communities and are trusted by communities…We also saw these child advocacy centres (CACs). There was one in Dallas, and we said that’s a great model because that’s a centre that people can come to and it’s not like having to go to a police station. It’s not so intimidating; it’s a bit friendlier. It’s a fun place for young people to go,” Svasti added.

“We also looked into American models. Because both myself and Dao have taken part in the US International Visitor Leadership Program…and we were taken to see projects which you could call community policing, where the police get close to communities and are trusted by communities…We also saw these child advocacy centres (CACs). There was one in Dallas, and we said that’s a great model because that’s a centre that people can come to and it’s not like having to go to a police station. It’s not so intimidating; it’s a bit friendlier. It’s a fun place for young people to go,” Svasti added.

A big reason that Svasti felt the trafficking wasn’t being solved was the police approach. “We looked at what we’ve done for the past 12 years which is mainly government agencies doing suppression operations. In other words doing raids on nightclubs, doing raids on illegal immigrants. Arresting them, putting them in prison, deporting them. The police hadn’t been catching many victims of human trafficking, but they had been causing a lot of bad feelings among the high-risk groups,” Svasti said.

The HUG Project and the Dallas Children’s Advocacy Center highlighted a different path for addressing human trafficking that focused on fostering a positive relationship with at risk populations and was more “victim centred.”

After seeing these effective projects, ACT Center was formed. “The ACT Center started as a think tank of like-minded organisations. [To this day], the centre isn’t one agency, it’s a consortium, a network of agencies,” Svasti said.

ACTing it out

“The centre has three facets; prevent, protect, and restore,” Kayty, a volunteer at ACT Center through the HUG Project, explains, as we stand in front of the cosy house inside the centre itself. “This is the prevention area.” The prevention area is where at-risk kids can come after school to play sports, do arts and crafts, and learn life skills. Many of these activities are conducted in the backyard of the centre. But there is also a kitchen inside where kids can learn to bake, and areas to sit and hang out inside. The leaders for this piece of the program are the Royal Thai Police Region 5 and HUG Project.

Inside, we enter a room with a tan plush couch, fuzzy carpets and bookshelves that look more like my friend in Michigan’s living room than an intimidating room for authorities to investigate. However, this is where victims come to talk with someone who has training in child psychology, and only when they are ready. It is easy to see why a victim would feel more comfortable talking here than in a stereotypical sterile police station.

The room connects with microphones and cameras to a room next door, where police can listen in on the interview and, through an earpiece, feed more questions to the interviewer. This way the victims are not overwhelmed with multiple people interviewing them.

Since March 2015, when the ACT Center began working in this space, and before the official opening, “22 children have been interviewed at the centre: 10 boys and 12 girls. After the victim identification process, 6 boys and 3 girls were confirmed to be victims of human trafficking or child abuse” (ACT Center Opening Speech).

When children go through the legal process, they are also provided 70 hours of one on one counselling, along with group counselling. Also, they are given a place to stay and financial support for rehab programmes if needed.

After seeing the counselling room, I cut across the yard to a long room with a piano and musical instruments to speak with Dao and HUG Project Director, Boom. Dao and Boom sit on pillows around a wooden table in the centre of the room. They both have warm and welcoming demeanours that, like the centre itself, make one feel instantly comfortable. They explain a little bit more about how ACT functions day to day.

“The ACT makes it more crystal clear what we are doing,” Dao explained.

“I think it’s become a more victim-centred approach. Basically in the past victims would be referred to a police station, a government shelter…You know, they were sent everywhere. Now they come here, and instead we all come to them,” Boom said.

She went on to clarify, “In the past victims had no idea what was going on so we kind of played a coordinator role for the victims. Now, instead of them having to contact everywhere, we help coordinate it all so they don’t have to meet new people all the time. We help with schedules, who they’re going to meet, what they’re going to do — help them prepare each step throughout.” Along with helping children through the legal process, ACT also provides housing (with one of the organisations under the ACT umbrella) and counselling.

“That is the legal process, but then ACT is about having activities for the kids in the at-risk group,” Dao added, again demonstrating their breadth.

ACTion

Boom and Dao were able to discuss a closed case with me about an American man named Gary Thomas living in Chiang Mai. In this case both Thomas and the pimp working with him, Ayo, were found guilty in Thai court.

“[Gary Thomas] was an American coming back and forth between Thailand and America for more than 20 years. His behaviour was strange. He didn’t go out anywhere. He just stayed at the guesthouse. Even the guesthouse was strange. It didn’t accept other guests, only him. Several boys were going into that guesthouse,” Dao explained about the prior suspicious behaviour that led to Thomas’s arrest.

“A social worker was working with the at-risk group until they knew what happened,” Dao said.

“We started the case together with the FBI. The Americans also opened the case, and then we had the kids ready. To have the kids testify in court is difficult…because the kids are extremely poor. But finally the social workers built a relationship with the kids.” Dao explained.

“We had a predator, and a person who supplied the kids. He got well paid by this American guy. Ayo was a victim before, but his age was over 18 by the time of his arrest. He used to have a romantic relationship with this American guy, but then he turned pimp,” Dao explained. Both of these men were sentenced. Aryo recruited many of the kids from online and computer game shops, a grave concern for many involved with ACT.

“Ayo admitted to 300 boys to me,” Dao said.

Ayo was sentenced to 24 years. “But he pled guilty so it was cut down by half,” Boom amended. Thomas was sentenced to 12 years. “But because he pled guilty he was sentenced to nine years and eighteen months,” Boom again amended. Since Aryo was the trafficker rather than the abuser he received greater punishment.

The US intended to prosecute as well, but Thomas “died two days after the sentence of a heart attack I think,” Boom said. This was just one of many cases, several of which are still in process.

Key Players

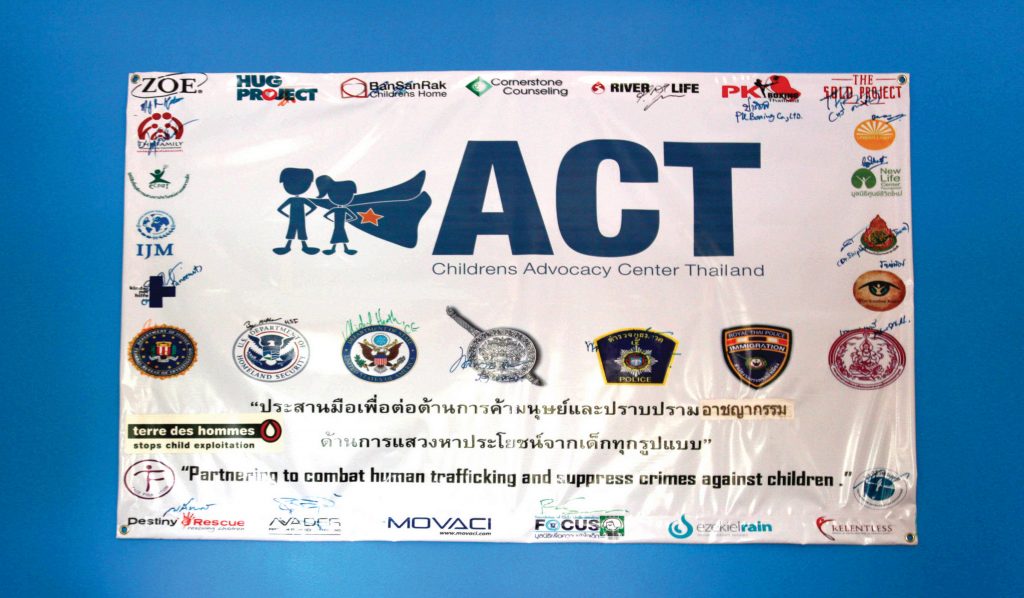

“[The ACT Center] is a pilot project in collaboration with the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation, Homeland Security Investigation, National Crime Agency of England, Italian Police, French Police, and Switzerland Police, among others. Thai organisations represented include Royal Thai Police Region 5, Anti-Trafficking Division, Technology Crimes Suppression Division, Division of Special Investigation, Office of Immigration Region 5, FACE, Zoe International, SOLD Project, FOCUS/TRAFCORD, ECPAT Foundation, Destiny Rescue Foundation, HUG Project, Ban San Rak, the River of Life, NVADER, and International Justice Mission,” the ACT opening speech explained. These organisations range in what they provide, from funding for the centre to information about potential traffickers.

I was curious about how the FBI and other foreign agencies came into play, so I asked Svasti about this.

“The US FBI and the British Police…worked with Dao before the ACT…and they were seeing that his approach worked, in which he was able to rescue kids and get prosecutions for abuses. He had good cases. So the FBI and National Crime Agency started to give him tipoffs. In other words paedophiles are quite often…on child offender databases. Sometimes the FBI might give a tip that a convicted child abuser has come to our area. Someone they’re following and they’re tracking. They would then say to Dao this guy came into Thailand. He has a case history, so keep an eye on him,” Svasti explained.

“Some of these cases they then take them back to the US to stand trial,” Svasti added, adding that the US authorities were very active in this issue. In March, US Under Secretary, Sarah Sewall, visited Thailand and, among other issues, addressed human trafficking. Sewall is the highest-ranking US government official to visit Thailand since the coup.

Boom, Dao, and Svasti continually express how much the centre depends on the coordination of all of these organisations — police, government and NGO — working together. I got the opportunity to see this collaboration later in the week when I sat in on a TIP Forum at the US Consulate. Representatives from many of these organisations, along with the US Consul General, Michael Heath, and members of his staff attended. Towards the beginning of the meeting the ACT Center was addressed. Representatives from different organisations addressed issues ranging from child sex trafficking to migrant labour. Everyone seemed eager to learn from one another in order to attack the problem of trafficking. Many saying that this ability of organisations to work together makes the Chiang Mai area unique.

Forward ACT

The organisers hope to continue to prevent trafficking through prevention activities, such as after school activities. They will also continue to provide counselling and assistance for victims of trafficking.

Also, organisers of ACT hope that it can be a model for other areas. They see ACT working potentially in Chiang Rai, since The Sold Project, based in Chiang Rai, is already one of the organisations involved in the current ACT Center.

I spoke with Tawee Donchai, the Thailand Director of The SOLD Project, and he said, “Nobody claims they own the ACT Center. It’s working together…open for anyone.” Hopefully this model of NGOs, police, and international government organisations will be applicable elsewhere.

All of those involved remain positive despite the great challenges they’re facing, and simply from talking to each member of the ACT Center team, I can sense the way they support one another, as well as the at-risk children in Chiang Mai.

“I’m not looking for someone super experienced. I’m not looking for someone super smart. I’m looking for team accountability and the trust that maybe one day we tell each other, hey, we need to rest. We can help each other and be there for each other when one of us is feeling down,” Boom said, demonstrating this support network.