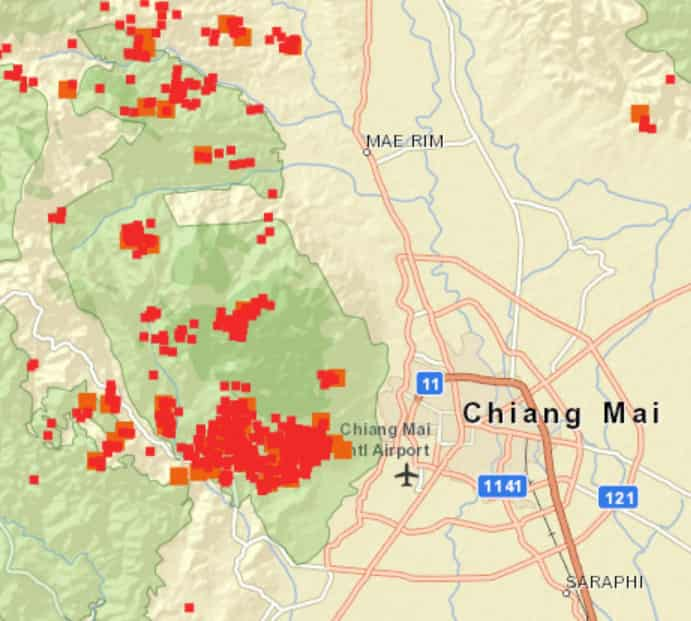

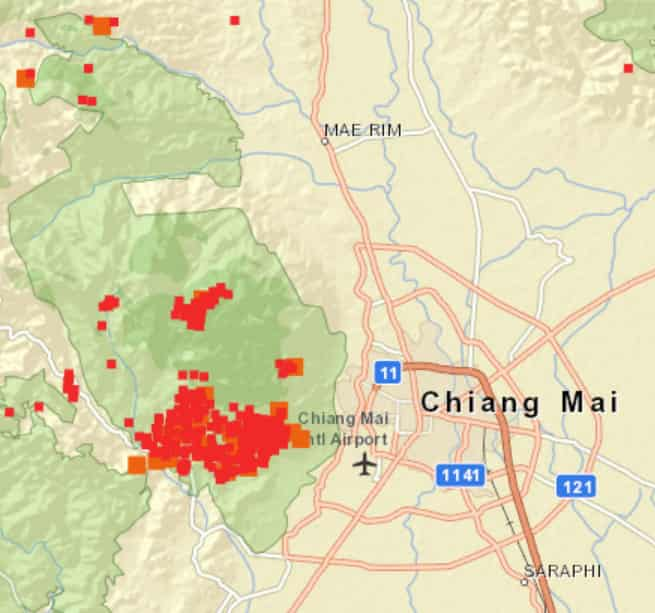

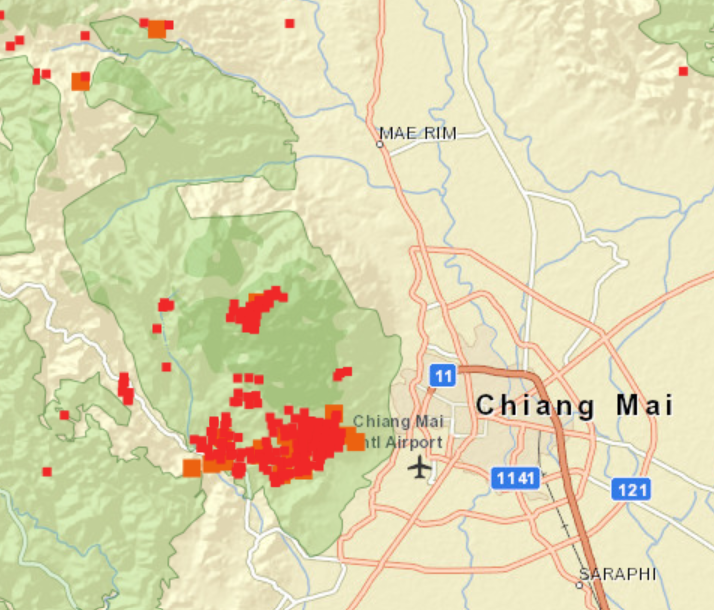

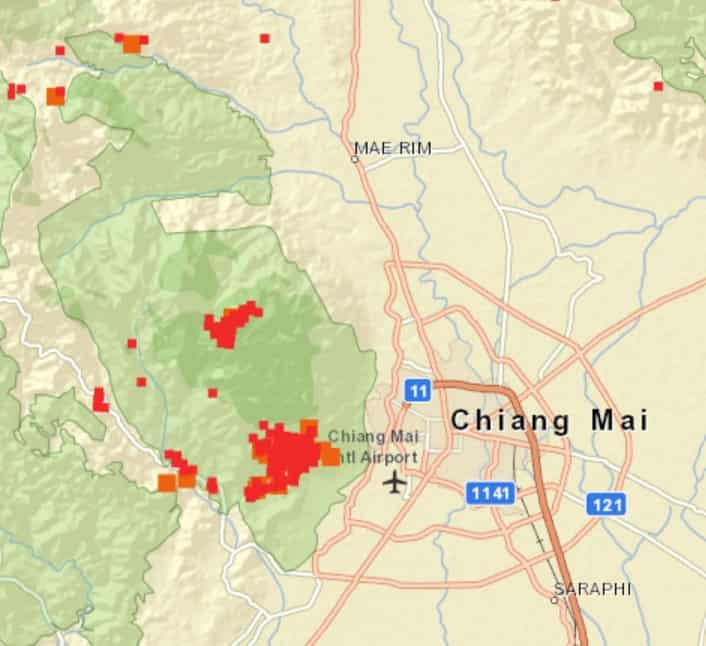

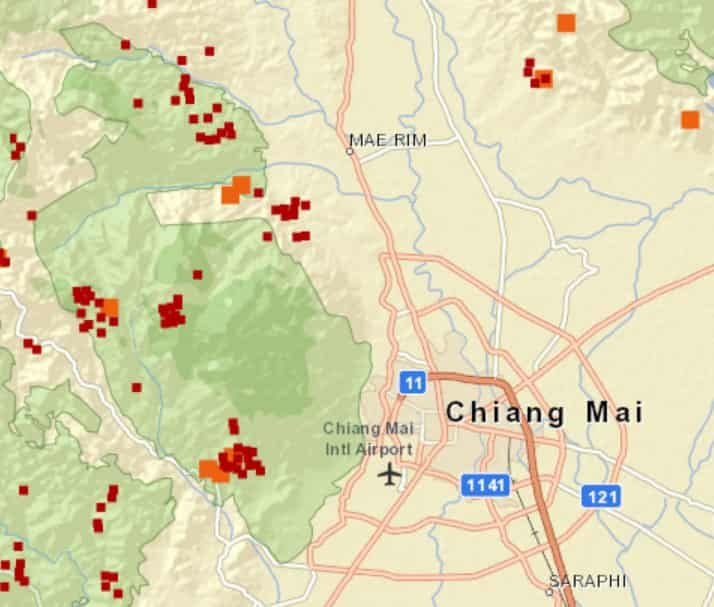

Our days are spent in seclusion; those with air-purifiers can shelter indoors from the worst of the particles and those without must worry about the future of their lungs, as the mountains next to the city burn. Massive fires are raging across the Doi Suthep-Pui mountain ranges, with one fire near Huay Tung Tao estimated to have decimated over 2000 rai of land. The largest fire at this time, however, is the cluster burning wildly to the south of the city on the Hang Dong side of the mountain range, perfectly positioned upwind to blow the smoke straight down into the city. Then there are fires creeping dangerously close to Doi Suthep Temple and Phuping Palace.

“Thirty years ago the fires were terrible,” said Dr. Stephen Elliott, Co-founder and Research Director of Chiang Mai University’s Forest Restoration Research Unit (FORRU-CMU) for a Citylife article about the health of Doi Suthep” in a 2017 article which is a must read for those wishing to understand the complexities of maintaining the health of our mountain range. “Then in the 90s-2000s there was a big push to organise the villagers in the park into fire prevention units. Each community was responsible for cutting fire breaks and patrolling their local areas. It worked quite well for many years but a few years ago that system seemed to be breaking down. Coupled with the drought this probably contributed to the severity of the fires in 2015 and 2016. Past fires mostly just burned leaf litter, without killing big trees, but the 2016 fires were so intense that they killed big trees over large areas. Just look at the dead trees behind the Montatarn Waterfall toll booth. So now there’s a massive amount of dead wood in the forest just waiting to flare up when the next dry year comes along. There’s a chance that the dead trees might rot away if we get several fire free years in succession, but that seems unlikely when climate models predict an increasing frequency of El Nino events due to global warming. Increased fire prevention is the only option; if it fails then the lower slopes of Doi Suthep will begin to look more like the Serengeti.”

It looks like that big year is here.

“It’s the same old problems we have always had really, just exponentially greater,” said Dr. Elliot today. “The underlying cause is too many people, in a nut shell. Too many people needing to be fed and the pressure on the park this year has been particularly high. Look at all the people cashing in on the tourism boom in Mon Jam.”

In Elliot’s 35 years of working to reforest the Doi Suthep-Pui mountain range, he said that this is the first year that he had actually seen old trees killed by fire. “The fire needs to be really hot and move really slowly to burn through the living tissue at the base which connects the roots to

the tree. If the fire burns that part then the top of the tree will die. A dead tree standing in the forest like that for a long time becomes tinder.”

“When many of the trees burned in 2016 they were left standing. It is these tall vertical dead trees which are spreading the sparks, whereas the traditional slow crawling fires would burn leaves and creepers low on the ground which wouldn’t send sparks flying in the wind. In three or four years, even with good wet years, we could have even worse fires as we are now seeing large trees burning.”

While Elliot has seen decades of work go up in flames over the past weeks, he is not giving up, saying that while he wants to weep, he must continue to find solutions.

According to FORRU, there are two main causes of fires in this area, those started by villagers at the edge of the forest who lose control of agricultural purpose fires, and mushroom hunters. Ben Svasti, of the Blue Sky for Chiang Mai group, who is currently overseeing eight firefighting units, each with around a dozen firefighters as well as volunteer villagers and community fighters, says that there is one more reason fires are being lit: villagers who are discontent with the government.

“Villagers feeling resentful towards the government, for reasons such as eviction from forestry land, are lighting fires”, explained Svasti. “It is tradition, it is ingrained, it is stubborn, and it’s unlikely to change. That is why the governor has been focusing efforts on the younger generations in hopes that they could affect change.”

“The forest will come back,” said Elliot with some hope. “The proportion of dead trees are still not too big but if the numbers increase, and the fires continue to come, then we will get savannisation. This could happen in thirty to fifty years. You will begin to see more treeless patches and soon there will be no trees left at all as there are simply not enough young trees growing old. It is the young trees which burn the most, the old trees are more resilient.”

“As far as I can see, we have one helicopter with an orange bucket,” said Elliot. “They have to fly so high that by the time they empty the bucket and water falls out the particles are so small they are ineffective. I was surprised, however, that authorities asked for help from people with drones. The images have been great in raising awareness about the fire and the technology is helping firefighters to pinpoint exact locations of fires.”

“We really wish that the military would help more,” said Svasti, whose eight units work closely with the various departments under the Minister of Environment and National Resources. “It’s very frustrating for the fire fighters that the army isn’t stepping in to help enough. The 2000 rai of land burned near Huay Tung Tao is all military land. The people who are putting out the fire are from the forestry and national parks. Why are they not putting out their own fires?”

Svasti went on to say that his understanding is that orders have yet to come from above. He says that when the military do step in on situations such as these, they tend to be very effective, which makes this current inactivity even more frustrating. Svasti’s units are well equipped (the Citylife Garden Fair, thanks to our readers’ generosity, donated over 60,000 baht

towards their efforts earlier this year), and there are plenty of blowers and rakes, which are helping.

“The problem is that the governor can’t tell the military what to do,” continued Svasti. “The governor has been very hands on and he knows what is going on, but unfortunately this COVID-19 crisis has diverted all attention from the fire issue, even though it is exacerbating health issues here. Chiang Mai was in fact very well prepared this year with the formation of the Breathe Council and the strengthening of civil society on the whole. But now on the community level there is not much support for the governor because of the virus crisis. And then there is the attitude of disgruntled villagers thinking, ‘if the government wants our forest back then they can jolly well care for it’, or something like that”. The main reason is that it is a traditional way of life.

Both Elliot and Svasti think that the annual Songkran rains will bring an end to this year’s fires, Svasti adding, “there won’t be much left to burn by then anyway.”

“At the end of the day, I don’t believe any leader, however strong, can stop villagers from burning, these are entrenched, stubborn traditions and ways of life.”

That it is why it is heartening that Elliot has a ray of hope for us.

While he is not yet comfortable sharing numbers with us, as the paper has yet to be published, he says that there is research out there that shows us a way out of this cycle: the business of carbon credits.

“The Thai government, specifically the Forestry Department, has been writing the REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) protocol for Thailand, slated to be published this July,” explained Elliot. “What this means is that if we can create a carbon market in Thailand, then it would be far more profitable for villagers to protect forests than to grow corn. More and more governments around the world are insisting that companies pay for their emissions over and above what they consider reasonable amounts. For instance, in the European market, it is 25 Euros per tonne of Co2 emmitted. Basic calculations show that by growing forests, you can make, in theory, double the amount per rai than by cultivating on it. If farmers have a choice to double their income, how would they react? I suspect there will be no more burning, so no pollution problems. Villagers will fiercely protect their patches of forest, because there are stringent international guidelines set by United Nations as to what forestry land is eligible for carbon credit exchanges. People can then make extra money from the forest by foraging for honey, mushrooms, even ecotourism such as bird watching activities. Let’s turn corn farmers into carbon farmers.”

The problem is that Thailand doesn’t have a carbon market and would need the government to create one. Until Thailand finalises its REDD+ strategy to qualify for carbon credits, this is just a dream.

“And don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of other obstacles,” explained Elliot, “such as middle men who take on roles as investigators and evaluators and such, they can take quite a cut of the profits, but once you reach the point that people can make money from the forest without hurting it, they will be its fiercest protectors.”