On a shady patch of well-groomed land, flanked by a gentle brook which separates it from the bucolic grounds of the Chiengmai Gymkhana Club, lies the Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery, a unique piece of real estate in Thailand, where foreigners may own small plots of land for perpetuity, a privilege only accorded at death.

The land is shaped like a pyramid, crowned at its northern tip by a bronze statue of Queen Victoria, her gaze fixed on the small chapel in front of her and the headstones spread out below.

This cemetery is the manifestation of the history of the past hundred or so years of the Chiang Mai expat community. The first American Presbyterian Mission was established by the intrepid Reverend Daniel McGilvary in 1867 and the British Consulate was opened in 1884, to support the administrative outposts in northern Thailand and eastern areas of Burma as well as the growing teak trade. By 1898 there were twelve Brits based in Chiang Mai with many more scattered in far flung stations and it was then that the British Consul, W.R.D. Beckett was asked to petition the Thai government for a grant of land to be used as a cemetery. King Rama V, signed, and in parts hand wrote, the Royal Deed of Gift of 24 rai of land to the Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery that year, incidentally the same year he also gave 90 rai of land to the foreigners of Chiang Mai to form the Chiengmai Gymkhana Club next door. The conditions of the gift were that the land may never be sold, that it may be used only ‘for the burial of the bodies only of foreigners’, and that the ‘British Consul be the custodian of the land in perpetuity’.

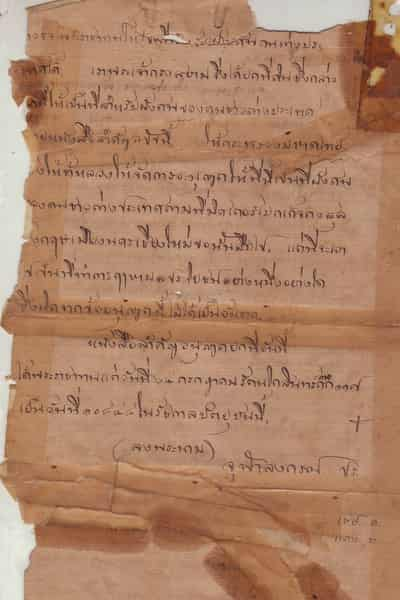

Royal Gift

“Mind you, we never had a title deed,” said Ben Svasti, Honorary British Consul who went on to explain that all land in Thailand at that time belonged to the crown. “In fact, any use of land in Thailand was by permission of the king. The land, similar to that of the club’s next door, was never to be sold nor used for commerce. The problem began to arise when even following the Land Act [in 1901], no title deed was issued.”

“We started burying people at the northern tip, near where Queen Vic stands today, and spread out south,” said Lt. Col. Ron Rae, a Scotsman who has sat on the cemetery committee since 1997. “At the turn of the 20th century, encroachment began at the southern border, and the custodian decided to be magnanimous and allow Thai villagers grazing rights for cattle and sticlac farming. Then in 1930 Dr. McKean, of McKean Leper Asylum, requested some land on behalf of the Christian cemetery, four rai of which has now been carved out and deeded through church connections for Ban Den Christian Cemetery.”

“Eventually we were going to crash,” added Svasti, “by 2012, we were down to just over one and a half rai of land. Something needed to be done. Because we had no title deeds, we had no teeth to negotiate with squatters…but we are getting ahead of ourselves.”

Losing the Plot

During the war, when foreigners were interred in camps and the Brits fled to Burma, the Thai military was billeted at the Chiengmai Gymkhana Club. For some reason, they believed that there was gold buried amongst the foreigners, and after the war it was discovered that the cemetery was, ahem, gravely damaged, with tombstones kicked over and smashed. Thailand, as reparation for the war, was instructed by the British government to repair the cemetery and once done, the custodian allowed local farmers grazing rights again, asking for a small donation towards the grounds’ upkeep. Soon families of consulate staff began to settle on the grounds.

“In 1967 a local newspaper called Pim Thai published a rabble-rousing report that foreigners were charging Thais money to use royal land and a very ugly mob rose up against the British Consul, Donald Gibson,” explained Svasti.

“The Thai authorities took the side of the locals and the consul reached out to the American consulate for help,” added Rae, “but they wanted nothing to do with it.”

“It was quite fierce, with riots and swords, and poor Donald was put right in the front line. He had to end all agreement for donations, and without title deeds, he was unable to evict. This was when the encroachment really took hold.”

The Plot Thickens

While the British consulate, the first of what is now 17 consulates and honorary consulates in Chiang Mai, opened its doors in the late 19th century, it has also closed them on numerous occasions, sometimes leaving residents bereft of a government representative, others appointing a local honorary consul such as Ben Svasti. Because the king’s proclamation was that the custodian had to be the British consul, it was therefore decided in 1970 to form a committee under the custodian, one which continues to care for our dead to today. Recently, noticing that there were more American ‘residents’ than from any other nation, it had been mentioned that the committee include an American representative. But, still smarting from the lack of US support during the Pim Thai riots, it was decided to maintain the current makeup of the committee, which is run by Brits, a Frenchman, a New Zealander and half Thai half British Svasti.

In 2012, the committee hired a lawyer who formally filed warning letters to squatters and petitioned the government for control. As of 2014, the land now has a title deed held by the district office and the municipality. They have power to administer and get rid of squatters and so far three extra rai have been reclaimed, “which should keep us steady for another 50 years or so,” beamed Svasti.

“Of course, clearing people out is not something an elected body like the municipality wants to do, so we are all being very conciliatory,” added Svasti. “For instance there is a 90 year old man who lives on about a rai and a half, we have talked to him and his family and assured him that he can live there until he is gone. The agreement with the authorities is that anyone who has built a house is allowed to stay on, but businesses who have built dormitories or commercial apartments must go.”

Guardians of Expats Past

The full committee meets once a year, though Svasti and Rae have frequent discussions about the day to day running of the cemetery, which costs around 130,000 baht a year, a cost mainly covered by plot fees of 20,000 baht per plot, or 10,000 baht for cremated remains as well as the odd donation from family members. The committee fondly refers to the ‘residents’ under their care, Rae taking great pride in, “personally having buried 118 residents”, easily quoting the dates and circumstances of every residents’ death from the cemetery’s inception to today. A caretaker also lives on premises, a far more sensible man than his father, from whom he took over, a man who used to fill his small house to the rafters with relatives in fear of farang ghosts.

The Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery committee publishes their finances once a year and keeps impeccable records of their dead. This is in great contrast to the Bangkok foreign cemetery which has been plagued with corruption and mismanagement, now barely accepting any new residents due to lack of land.

“We have to watch out for Bangkok undertakers who are always trying to get us to bury their dead,” said Rae who explained that ten years ago he was nearly hoodwinked into burying a Belgian aristocrat, before thankfully discovering that she had never ever been to Chiang Mai and had only spent a short amount of time in Thailand before passing away.

“Many Bangkok residents have requested to be buried here,” explained Svasti, “but we have to be judicious and that is why it has been decided that you have to have been a resident of Chiang Mai for three to four years to book a plot. Of course if a tourist has an accident and dies, they can also be buried here, but only residents can book. And as per the Royal Gift, only those holding foreign passports, so Thai spouses can be buried only if they have dual nationality.”

With only half a century worth of plots available, the committee’s job is to work towards the expansion of the cemetery while also caring for the grounds and all its residents.

Juicy Obits

In 1980, the first edition of De Mortius was published, according to its preface by Major Roy Hudson because, “from time to time during the last few years some of us, who have made our home in Chiang Mai and are not getting any younger, have expressed the thought that a history of the Foreign Cemetery in Chiang Mai should be written by one of our members before we end up there ourselves,” and Major R. W. (Dick) Wood was tasked with the challenge. Dick Wood’s father had been a founding member of the Gymkhana Club the same year the cemetery was founded and between father and son were members for over 100 years, until Wood’s death in 2002.

While death can be sad and tragic, De Mortius is a celebration of life, not of death. And thanks to the at-times ruthless wit of Wood, De Mortius is a highly entertaining read that also offers a fascinating insight into the history of Chiang Mai’s expats. There was no one more knowledgeable about expats past, and together with his friends Roy Hudson and Donald Gibson, he wrote a book filled with charming personal anecdotes and insights which would have been lost to history otherwise. Though sales have been far from brisk, the last edition only selling 300 of its 700 printed copies, with 40 new ‘residents’ since its last edition, this year will see the publication of its 7th edition. Incidentally, Maj. Roy Hudson, wondering over his own mortality in 1980, is still alive and well, and at 96 years old has no prospects of becoming a resident anytime soon, even returning his booked plot a few years back.

“On the 23rd of January 1900,” De Mortius’s Story of the Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery begins, “there rode into Chiang Mai from Kentung Major Edward Lainson Guilding of the Essex Regiment, in the last stages of dysentery. What he was doing here no man knew,” but Wood speculated that he was part of the Great Game whereby the British watched the moves of Russia. He soon died on Valentine’s Day at the age of 43 and his grave is numbered, A1, being the first in the cemetery.

A2, likely due to early insiders’ booking, lies Donald Gibson MBE (1920-1998) whom, as consul and custodian, also insisted on writing his own obituary, noting that he was hailed for his bravery behind Greek enemy lines during the war and while he spent his life as an officer, diplomat and businessman, excelled most as a linguist, speaking reading and writing at least thirteen languages perfectly, including Thai and kham muang.

Others were not so quick to escape Dick Wood’s pen, which he conceded in the forword to the 4th edition of De Mortius, was not mightier than the reaper. Though Rae says that Wood took certain liberties with facts in face of telling a good story, it is these stories that make for such an entertaining read.

Though Wood never met Reverend Daniel McGilvary, who died in 1911, his father did, and the inimical relationship between the godly American missionaries and the rather rambunctious British teak wallahs can be felt in Wood’s cheeky obituary of the legendary missionary.

“So this was the call! A new country! A land ripe for picking, a pagoda tree to shake, not for loot but for souls!” he wrote of McGilvary’s calling, going on to talk of his arrival in Chiang Mai in 1867, “into his Promised Land he strode, like Moses, to whom according to old photographs (and Michelangelo) he bore a striking resemblance.”

On mentioning the mission’s early successes, Wood wrote that that year, “included the elimination of white ants from the hand organ and the library (apparently undeterred by the dryness of Dr. Alexander’s commentary on Isaiah).”

Old friends were not spared Wood’s pen as he wrote about a member of the esteemed McFee Family, Angus, who died in 1989, telling of how he returned to Thailand, after the war, not having seen his mother for thirty years. “Her first action was to give him a bath, aged 36.” Angus continued to live in Chiang Mai until his death and while he was, “usually presented by his relations with eligible girls (whom he thoroughly enjoyed) he always seemed to escape, quite honourably, from matrimony.”

Robert Elder, a fellow Brit, was also eviscerated by Wood, who while wrote that “he adored his mother,” went on to say that he lived in ‘Ammonia Villa’ owing to his incontinent cats, going on to mention that, “he neither smoked, drugged nor drank. Nor, one was almost persuaded, ate and possessed one tooth in his front upper jaw.”

A highly distinguished resident, Henry Garrett, who was a recipient of the Order of the White Elephant, was, according to Wood, nicknamed ‘Granny’, “from his habit…of ‘scratching around like an old hen.”

Sadly Dick Wood’s own obituary lacks the colour and flavour of those he wrote for others, though still tells of a life worthy of the epitaph on his gravestone which simply states, “Asian Legend.”

Grave Expectations

The cemetery currently makes room for around five new residents a year and while plots are comfortably laid out, it is with great relief that the committee finally managed to reclaim so much land.

“When we showed Thai authorities, from the governor to cabinet members, the Royal Deed of Gift written in King Chulalongkorn’s hand,” Svasti says, handing the plastic-coated document with great care, “they all wai it with great respect. This document has been passed around from department to department for years, and we are thankful that we now have the official title deed, even though it’s not in our name, but one which gives us our rights back. The cemetery has weathered many storms, but we are in good shape now.”

The Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery, if you haven’t been yet, is well worth a visit. Old headstones offer captivating insights into the past, telling stories and inspiring the imagination. Make sure you stop by the old caretakers’ house on the grounds to grab a 200 baht copy of De Mortius.

The Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery Committee is also actively seeking donations towards the cost of printing the 7th edition of De Mortius as well as to clear the reclaimed grounds of rubble. Donate here:

Jonathan Charles Wood (committee treasurer) or Lt. Col. Ron Rae

UOB

717-165-923-3

Under the Royal Gaze

During the war, according to an article in the New York Times in 1990, she was boxed for protection, though, “two holes had to be drilled near her eyes so she could continue to gaze down on her devotees.” Upon hearing that she had birthed nine children, she rapidly became revered as a fertility goddess by locals, evidenced by her shiny foot, rubbed to great lustre over the years by barren locals. When the consulate was closed in 1978 she was moved to her current location at the cemetery, and in spite of occasional requests by the new owners of the consulate for her return, it has been decided that she is best left overseeing the dead.