Some people talk a lot of green, others like to play around with green; but while some may scoff at green or reject green entirely, there are a few good people who take their green very seriously. Let’s meet some expatriates in Chiang Mai who do just that.

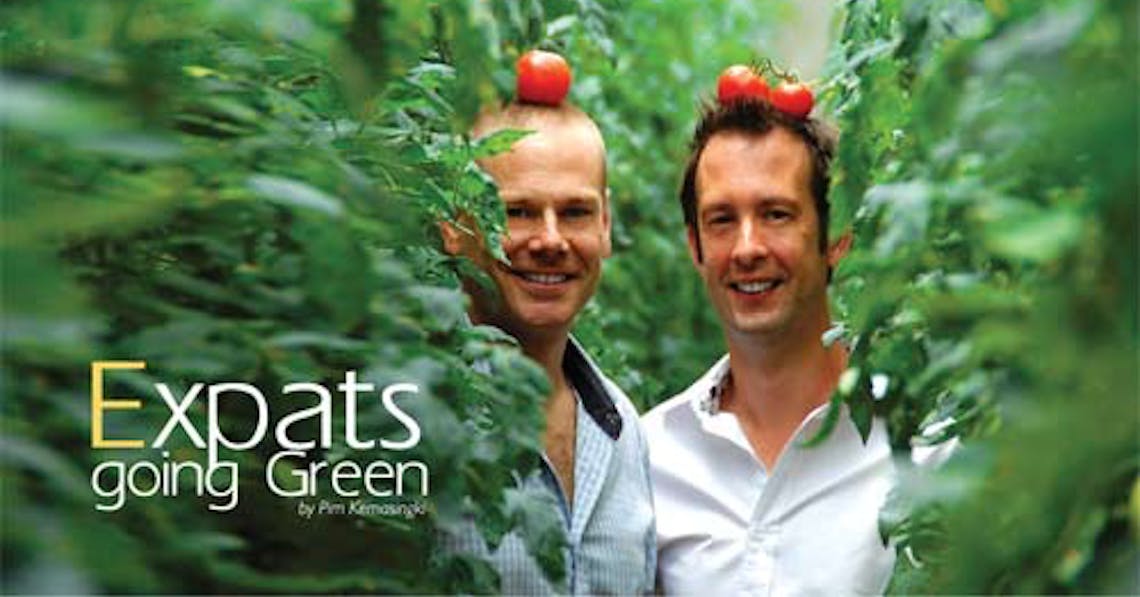

Take me Home Tomatoes

Idealistic Entrepreneurs

High up the Mae Sa Valley, two Dutch men in their early thirties are pioneering hydroponics technology, growing tomatoes safely and creating a low environmental impact. If you are a shopper of Chiang Mai’s supermarkets, you will no doubt have been tempted to heed the pleas of their brand ‘Take Me Home’ as well as tempted to bite into the perfect and juicy tomatoes on sale.

“First of all, what is organic,” asked Menno Keppel, one of the two Dutch shareholders, “and how far do you go with it? In our business model, organic is labour intensive and expensive, it is simply not feasible. We are in a sense, opposite to organic, because we are influencing nature. Hybrid tomato varieties and synthetic fertilisers are not organic.”

“But our priority here is that our food is safe and responsible,” added Thomas Ruiter. “We have studied up on this and we have high safety standards. We have knowledge of the local pests and diseases and their life cycle and this helps us to get rid of them with minimum impact to the plant, environment and food safety.

We do use chemical crop protection methods, but by the time our tomatoes are on the shelves, there is no trace of chemicals left. We also know when to use chemicals and when to use biological crop protection. Most (Thai) farmers don’t have this knowledge. We are responsible growers. We control what we produce and how we produce it and provide food which is absolutely safe to eat.”

“As a matter of fact,” chimes in Keppel, “in a residue test, you can’t tell the difference between a 100% organically grown tomato and ours.”

Keppel and Ruiter were university friends who ended up in the same job upon graduation. Though their background was not in agriculture, their company sent them to Chiang Mai, in fact, to the exact area where their business, D.A.T.T. sits today to conduct research on hydroponics in 2003. Still in their early twenties, the two decided in 2004 to return to Chiang Mai to open their own business.

“We were middle men,” said Keppel. “We bought fertilisers, mixed them up at night, went to the Riverside for a few beers, and woke up and did it all over again. We also supplied Dutch seeds to Thai farmers. After a few years, we began to do consultancy work, helping farmers in the area, and eventually we began to do contract farming, training farmers to grow tomatoes responsibly and we would then market them.”

“At first we had the product, but didn’t have a clue how to market it,” said Ruiter with a laugh, “Our first harvest produced two tons of beautiful red tomatoes which we took to Muang Mai market to sell at 3 a.m. We sold three crates all night because everyone thought they looked too plastic, too fake. So, we decided to drink some beers and drown our sorrows, unfortunately we didn’t pack the tomatoes properly onto the truck and as we drove off we lost the entire batch turning a corner!”

Since those early fumbles, Ruiter and Keppel have gone on to great success, with Ruiter focusing more on the farming side and Keppel the marketing, “our pioneering days are over,” added Keppel with a grin. Their first customer was Rimping Supermarket in Chiang Mai, and today they sell in the Villa in Bangkok as well as to numerous chains in South East Asia and beyond.

“Because we pick our tomatoes when ripe on the vine, and fly them out, our products cost an extra 30 baht per kilo on arrival in Singapore just from freight cost. But this means that our tomatoes are much tastier than those which are normally picked green and allowed to ripen on a long voyage.”

The Dutch duo currently oversee 50 rai of hydroponics tomato farms, producing 500 tons per year, which they expect to double next year. “Of course we want to be as green as possible,” insists Keppel, “but it needs to be feasible. In fact we are studying many ways to become more organic. But the fact is there is not enough food to feed the world and hydroponics technology allows for bigger kilo per square metre. It also doesn’t harm the soil, since we grow in bags filled with coconut husks, so our fertilisers don’t have any environmental impact. We believe in helping farmers in the region to grow responsibly and sustainably, importing Dutch horticultural technology and adapting it to local standards.”

“We’re here for the long haul,” concluded Ruiter “we intend to expand to new tomato varieties, packaging, storage and other related sectors in the years to come. We are not organic in the pure sense, but we are in the sense that our products are safe – that is our interpretation.”

“Yes, we are entrepreneurs,” says Keppel, “but we do have ideals too.”

www.takemehometomatoes.com

Good Wholesome Compost

A Responsible Capitalist

Why would a wealthily retired Swiss man and his Thai wife of 35 years, move to Chiang Mai, where they had never lived, and open an organic fertiliser factory? Hardly the sexiest of enterprises and with a long projected return on investment, this manufacturing plant is also an inconvenient hour or so’s drive towards Phrao, far from Chiang Mai city.

“I’m doing this for a few reasons,” said Jacques Cavin, in a beguilingly soft voice for such a large man, “I stopped working when I was 54 as head of Human Resources for Philip Morris, and my wife and I felt that society had been kind to us, acquiring money was no longer an aim, we had enough to sustain ourselves as well as our envies. We wanted to do something for others. We didn’t want to do an NGO, but wanted to be responsible citizens and do good for the society we live in. So, we moved to Thailand five years ago, and three years ago we moved here to open Natural Agriculture.”

With a capital of 30 million baht, they began their new venture. Cavin, with his background in economics, had a friend in Switzerland who owned an organic fertiliser plant and he felt that he wished to emulate their principles here in Thailand, while utilising his management skills. “I talked to many government departments, as well as experts at Mae Jo University and received much support from some of them, combined with my own research, I am confident that we can produce high quality organic fertiliser in an environmentally and socially responsible manner,” he continues. “There are 10,000 rai of teak forest nearby and when they are logged, we receive all the wasted leaves and branches, which previously would have been burned. We can’t use corn in Thailand as there is too much GMO, but we also receive a lot of grass and brush when they are cleared to prevent fire.”

Cavin takes his fertiliser very seriously and is a firm believer in the importance of organic products. “Chemicals are dead, they do nothing for the soil, it is important to put something living in the soil,” he says. “By planting, you are forcing nature, you take out from the soil more than you put in, and more than what it is able to give. You therefore need to put back, organic adds humidity to the soil as well as micro nutrients and air. I think that every chemical fertiliser bag should have a warning like on cigarette packets _ ‘will kill soil’.”

Slickly Swiss, the operation is run smoothly and with great efficiency. With 15 full time workers and up to 30 daily workers – anyone who turns up in the morning is guaranteed 180 baht a day’s wage – the company is a sustainable development company with an ISO 2600 certification. Each truck bearing leaves, grass, or manure from nearby pig or chicken or elephant farms is weighed, logged in and all details catalogued for precise records and future analysis.

“Apart from teak leftovers, we also receive a lot of manure,” says Cavin, as we walk around his large plant, which is oddly aroma free, “a lot of pig manure in this region, like the elephant manure at the various camps, goes straight into the river. A farm near here has 100,000 chicken and they can’t cope with 2.5 tons of chicken manure a day, so they just dump them. We took 30 workers and after three months we cleaned up all their manure and brought it here. We didn’t pay for it of course, but it has value to us.”

Building-sized piles of fertiliser steaming with heat, sit waiting for packaging (Cavin uses recycled sacks, foregoing his own branding) and transport. Six plastic-lined water reserves, containing liquid fertilisers of various stages, keeps the entire operation nourished and hygienic. “I am very passionate about water management. We don’t think it is a problem here because Chiang Mai doesn’t really have water shortage or excess issues, but we should think about those downstream, instead of building dams along the way, we should simply start the practice of water storage up here at the source.”

Most of Cavin’s fertilisers take up to 14 months to rest, with occasional turns, to be ready for sale. His exacting standards have led his fertiliser to be dubbed the Rolex of compost. The objective is to produce 100 tons a month, an aim which is not far off. After being in business for nearly three years, he expects to break even in two more and begin the payback in seven to ten years.

Most of his clients are in Fang District and Chiang Rai, ideally he wishes to sell only to farmers within a 50 kilometre radius, to reduce transport impact on the environment.

While Natural Agriculture has a way to go to achieve its third aim of being economically viable, Cavin can be proud to be living his first two ambitions and that is to have a socially and environmentally responsible company, “after all, I like to consider myself a responsible capitalist.”

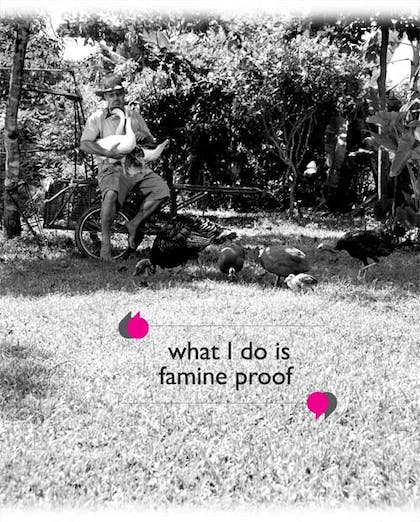

Ee-ei-ee-ei-Organic

A Radical Environmentalist

Jeff Rutherford is passionate about his small farm. In fact, Jeff Rutherford is pretty passionate, full stop.

“I am a radical environmentalist,” he announces, as we walk through his three rai farm in Mae Rim. “I grew up in Illinois, so although I was interested in nature, rows of corn didn’t really do it for me, so when I moved to California and lived on a forest commune, publishing a hippie newspaper, I began to get really keen.”

Having met his Thai/Chinese wife while studying in Taiwan, the pair moved to Chiang Mai in 2001 when Rutherford began work at the Social Research Institute, CMU.

“As I looked into problems with drugs, with deforestation and human rights, it all became clear to me that it all boils down to food,” he explains, while petting one of his two pigs. “Highlanders with bad land find it hard to grow vegetables, so they resort to drugs; deforestation is simply bad food management; and human rights gets abused when the governments try to ‘protect’ forests by taking land away from those who need food. Overall, bad food management causes so many problems in the world and if we can change the way we grow, consume and trade food, then we can solve some of them.”

Rutherford’s farm consists of a small paddy field, which supplies enough rice for his family and visitors, a stream with fish, a pig pen, as well as an astonishing variety of indigenous plants, some so rare and forgotten that regular groups of students and people interested in Lanna renaissance come to visit.

“A quarter of greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to the food system,” sighs Rutherford. “What I do is social enterprise because of my passion for the larger cause has to be translated into the way I live. I believe in green business, in gorilla capitalism, in the grassroots, fighting the powers by being successful in our integrity. We all eat three times a day, well maybe five in Thailand, and the sheer amount of money which goes into the industrial food system is destroying the world. It impacts the earth in a science-fiction like way. This can’t continue.”

As we are introduced to plants and trees, geese wander by, a guinea fowl waddles past, chicken cluck, cats prowl and even a tiny African hedgehog twitches its nose form the front of the house.

“I want to walk the talk,” says Rutherford, “so three years ago we bought this piece of land and decided to make it completely organic. This farm now allows me to communicate my thoughts better. I can walk for days around here explaining details of what I am doing and why it’s important to people who are interested. In fact, we have numerous visiting groups, locally as well as from Burma, Cambodia and beyond. We also organise what I call, ‘farm-shops’ fairly regularly for those who wish to implement or learn about this system.”

Rutherford is self taught, he spends his days learning from farmers, reading up on theories, studying from experts and most importantly making mistakes from his trials and errors. “This is a permaculture way of living,” he adds, “being in harmony with nature is totally contrary to the way of today’s society. I don’t want to dominate or control nature in form or fertility, but I want to recover degradation, reduce materials, create more nutrients and fruition. What we have here is a mini food forest; we’ve mimicked the under forest, the shrubbery layer, the canopy, the herb layers…”

The farm doesn’t look much to the amateur, but it begins to make sense as Rutherford explains each plant’s function. Some plants are there merely to be cut down and used as fertiliser, a hard sell to people who believe in generating an income from everything planted. Pigs root for cassava, acting as natural hoes, their waste going into the canals for the fish to consume – “I am a shit connoisseur” – and once a year the fish’s silt is dredged for fertiliser.

“What I do is famine proof,” says Rutherford. “Diversity is better for the economy and offers solutions when one crop fails. Our chemical neighbour’s yield is also reducing, so he has to use more chemicals, which increases his costs, while mine is increasing in value. Thai farmlands are like orphans, no one is taking care of them.

While Rutherford’s farm is in its infancy, he estimates another decade’s efforts will produce enough yield to sustain his living. For now, he sells his labour as a consultant, he holds work- or farm-shops and he continues his crusade…while walking the talk.