“When approaching the intersection of Chang Klan and Sri Donchai Roads, a sense of loss pervades. Here on the Southeast corner of this busy intersection rests the colossal of Chiang Mai cinemas, rotting mercilessly. Bound like a sedated hostage in the cheapness of billboards and advertisements, the sole surviving relic of Chiang Mai’s movie-going glory days awaits an undetermined, likely grim fate,” writes Phil Jablon in a post on his blog, The Southeast Asia Movie Theater Project, about the now decrepit Sang Tawan Theatre in Chiang Mai.

The language Jablon uses to write about the Sang Tawan Theatre can only be described as intense and despairing. He feels a special connection to movie theatres, especially those (like the Sang Tawan), that were once centres of community and culture, but are now nothing more than abandoned mammoths of a time long forgotten. Each post features a different Southeast Asian stand-alone movie theatre, complete with the theatre’s history, photos and musings about its future. Unfortunately, for many of the theatres, Jablon can only imagine futures of destruction and dust, of strip malls and duplexes.

But his project is not merely about documenting sadness. Rather, Jablon hopes that his work might help to inspire change and preservation. In a presentation he gave recently at the Alliance Francaise in Chiang Mai, he shared photographs from some of his favourite movie theatres throughout Southeast Asia and spoke profusely about the need to find sustainable solutions to ensure that these relics of architectural ingenuity and creativity don’t fall to rubble under the weight of apathy and misunderstanding.

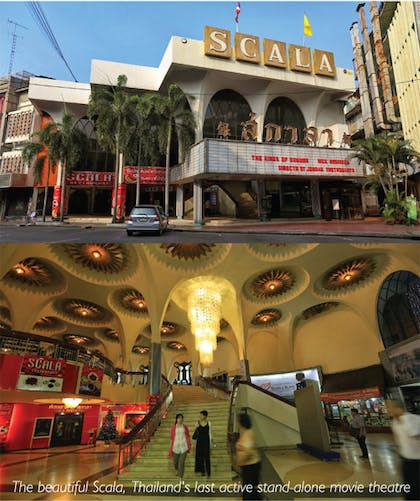

“Thailand is regularly losing good architecture,” wrote Jablon in his most recent blog post. “In particular, it is regularly losing good mid-20th century modern architecture, the same time period corresponding with a boom in movie theatre construction.” He attributes much of this loss to major corporations gobbling up land occupied by historic movie theatres so that they might build chain restaurants and strip malls, a fact that he, most understandably, thinks is tragic. Even Bangkok’s famously gorgeous Scala Theatre, the last active stand-alone theatre in all of Thailand – which recently won an award for architectural significance from the Association of Siamese Architects – has had its land bought up by ThaiBev Co., the company that produces Beer Chang and Mekong Whiskey.

Though Jablon has since returned home to the United States for the summer, he agreed to answer some questions about the importance of stand-alone movie theatres in Thailand and the history of movie-going in Chiang Mai, as well as to give some advice to our community about how to protect the Sang Tawan Theatre, the last of the great Chiang Mai stand-alone theatres, which we could lose at any moment.

Citylife: What led you to start The Southeast Asia Movie Theater Project?

Phil Jablon: The discovery of a rustic old stand-alone movie theatre in Chiang Mai. Prior to finding that theatre – the Tippanet Theatre – my only knowledge of movie theatres in Chiang Mai were the multiplexes in the two existing shopping malls.

By the time I got around to going to see a movie at the Tippanet, however, it had been demolished. It was then that it occurred to me that this was the likely fate of stand-alone movie theatres across Thailand. So I made up my mind that I would document them for posterity’s sake.

Citylife: What is it about movie theatres in particular that captivates you?

Phil Jablon: There are numerous aspects about these old movie theatres that are remarkable. First of all, the geography of the stand-alone movie theatres of yesteryear is much more human in scale than the multiplex theatres that dominate today. The former were usually built in town centres, or in densely populated outlying districts. Whether facing onto a throughway or tucked away within a plaza, they enliven the street with their architecture and the way people use them.

For instance, when a large crowd attends a movie in a mall cineplex, they drive into the parking garage and then back out when they’re done. They never set foot on the street, which in turn makes the street feel lifeless. On the other hand, when a large crowd attends a movie at a stand-alone theatre, the surrounding area benefits from a flurry in foot traffic. There’s something magical about that.

Citylife: Why is it important to save these stand-alone theatres? What do they offer that sets them apart from mall cineplexes?

Phil Jablon: The stand-alones were built solely for the purpose of watching movies. Cinema, we have to remember, is the most dynamic art form. The fact that there were once grand buildings where entire communities congregated for the shared experience of watching movies speaks volumes to this fact. Ensuring that a select few old theatres are preserved is good for the legacy, economy and vitality of the societies that claim them.

Citylife: The last of these great stand-alone theatres in Chiang Mai is the Sang Tawan Theatre. What makes this theatre special and important?

Phil Jablon: Truthfully, the most important thing about the Sang Tawan is that it’s Chiang Mai’s only remaining stand-alone movie theatre, which means that it represents the last chance for the city to reach back and salvage a piece of its cultural history.

That aside, it has a beautiful terra cotta mosaic on the facade depicting northern Thai village life. Sadly, that is now completely covered up by a huge billboard bolted to the facade.

The Sang Tawan is also part of the legacy of Chiang Mai’s royal household, as the builder was Jao Chai Suriwong Na Chieng Mai. I feel that that fact adds to the sociocultural importance of the theatre.

Citylife: What is the history of movie-going like in Chiang Mai?

Phil Jablon: Chiang Mai’s first permanent movie theatre opened in 1922, the same year the train line reached the city. The theatre was called the Patthanakorn and it was located near the Night Bazaar. Sometime in the 1940s, the Patthanakorn was sold and renamed the Sri Wiang Theatre – later to become the Wiang Ping – before it was demolished in the early 1970s.

By the mid-1970s there were about 13 movie theatres throughout Chiang Mai, representing just about every densely populated area of the city. Two of those theatres – the Sri Visan and the Chintatsanee – were owned by the father of current Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra.

The largest theatre magnate in the city, however, was Jao Chai Suriwong Na Chieng Mai. He built four theatres throughout the city, including the Suriwong, Suriyong, Suriya and the Sang Tawan theatres, the last of which is still standing. at the intersection of Chang Klan and Sri Donchai Roads.

Citylife: A lot of your work focuses on finding sustainable ways to renovate these abandoned theatres. What are some feasible, sustainable solutions for the Sang Tawan Theatre in Chiang Mai?

Phil Jablon: Ideally, it will be turned into a mixed-use venue, able to accommodate both film and live events, be it concerts, speaking engagements or plays. With the right cooperation, it might also have space for a small museum on the history of film in Northern Thailand.

The location of the Sang Tawan makes all this feasible. It’s right in the centre of the densest concentration of hotels in the city, which would make it highly accessible to the tourist market. Imagine coming to Chiang Mai, staying at a gorgeous hotel like the Anantara or the Shangri-La, and being able to enjoy a classic Thai film in a restored movie palace!

If the greater Chiang Mai community has any interest in being home to a rare and prestigious structure in the form of a revived stand-alone movie theatre, then this is the last chance to do so. Once it’s common knowledge that there’s a beautiful old movie theatre slowly rotting at one of the most important commercial/cultural intersections in the city, the advocacy stage must begin, building a case for why this structure should be invested in. Given, this is going to be an expensive project. Returning old movie theatres to their original splendour always is. But the return in the form of cultural capital for Chiang Mai and greater Thailand would be incalculable. Think of it like this: If the Sang Tawan is revived, it would mark the first time in the history of Thailand that a stand-alone movie theatre was brought back from a state of near-abandonment. That would be something to be proud of!

Citylife: Thai PBS recently did an excellent video piece on The Southeast Asia Movie Theatre Project – how else are you aiming to promote your research? A gallery exhibition or a documentary, perhaps?

Phil Jablon: Yes, I am currently exploring options for making a mini-series about Thailand’s old movie theatres. If this comes to fruition, it will air on Thai TV. The other upcoming event is a photo exhibition of my work at the Khum Chao Burirat House on Ratchadamneon Road. That will be held in cooperation with the Faculty of Architecture at Chiang Mai University and take place towards the end of the year. It’s my secret hope that that exhibition will mark the beginning of a campaign to restore the Sang Tawan Theatre.

While not focused exclusively on movie theatres, the Thai Film Archive in Salaya does have some material on the subject, including a Thai film museum containing some artefacts from old movie theatres. The Film Archive is, however, a fabulous resource for learning about another extremely understudied aspect of Thai culture – Thai cinema. They regularly show old movies at their Sri Salaya Theatre, many of which they possess the lone existing print of. They also transfer some old Thai films onto DVD for sale.

For more information on The Southeast Asia Movie Theater Project, visit Phil Jablon’s website: www.seatheater.blogspot.com