“Pretty much anything that you can think of you can build here,” Nati Sang explains casually. He’s just finished giving me the grand tour of his open-planned Makerspace office near Tha Pae Gate and

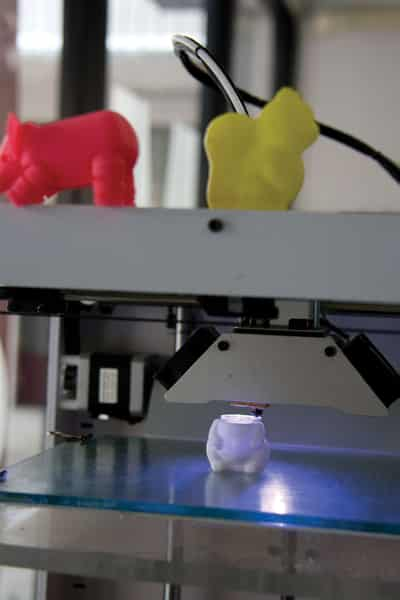

“These are our Ultimaker open source 3D printers,” Nati explains as we peruse the three mysterious boxes perched on desks that line the large plate glass windows at the front of the shop. “They’re made right here in Thailand, they print in two different types of plastic, one is the same plastic they make Legos out of, and the other, PLA plastic, is made out of corn starch.”

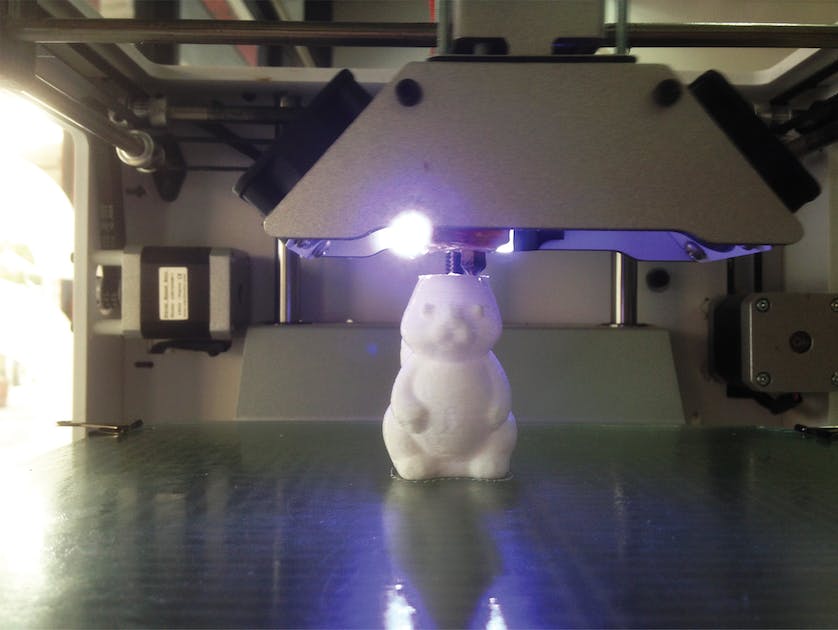

Nati inserts a memory card into one of the machines, and a tiny computer begins to load some 3D data as a thermometer on its digital display begins to rise. “It has to heat up first, but let’s print out a bunny, that’s usually how I teach people how to use the machine.”

“Over here we are experimenting with what’s called ‘photo telemetry’.” He picks up a white plastic bust of a monster, “this is just a topper for a cup when you go to a movie, it’s from Guardians of the Galaxy, but I was just experimenting with this method. Basically, you take 26 photos of something and the software creates a 3D model automatically. I hit print, and this is what comes out.” Nati shows me the actual cup topper and the printed out version. While the printed version is pure white with no colour, it is almost an exact replica. “It’s near HD quality, and all I did was take some pictures.”

But Makerspace is much more than a place to make copies of your toys. Nati’s vision expands way beyond access to the equipment itself, which includes 3D printers, a CNC machine, a high powered laser cutter, a fully equipped wood shop, and a microelectronics lab on the way. “I want to democratise the ability to access these tools,” proclaims Nati, “but I don’t really want to make money off of them.”

Access to Makerspace is membership based. Members pick how frequently they want to access the workshop and choose a plan, with packages starting at 1,500 baht per month. From there they pay for time on the machines, which is incredibly low. In fact, charges at Makerspace are generally one tenth the price of other workshops, you can print your own 3D bunny for as low as 30 baht an hour. “It’s really just to cover the cost of operations. We don’t want to make a huge profit off of people experimenting with the tools. We just want people to use them.” And people are.

“I have a variety of people come in. At first it was just farang. They’d come in and be like ‘Cool! A makerspace!’ because they kind of knew what it was. But then Thais began to come in as well.”

Nati, in fact, firmly believes that Makerspace is a place where Thai people can hone their inherent skills. Nati is of Thai heritage, born to two Thai doctors in Chicago, IL, USA but didn’t find himself in Thailand until early adulthood, almost by happenstance, after learning about some vacant property owned by his extended family. The timing was perfect. Nati had just witnessed the decline of the dot com era first hand working as an IT professional in Silicon Valley, and decided to jump on the opportunity to explore his roots by moving to Bangkok.

The next few years would see him dabbling in a variety of industries including recycling, weaponry, and a certification with the Lego Group in what is known as “Lego Serious Play,” a visual method used by organisations all over the world, including NASA, to create business strategies and increase productivity. His businesses were lucrative, but Nati’s ever curious brain eventually began its inevitable process of self-examination, and he found himself wondering if his work had any lasting impact. “I’ve always wanted to be an innovator,” he reminisced, “but to be an innovator requires change. I didn’t know if my work was actually making any change in the community,” and with that thought, Nati slowly began to lay the groundwork for what would become Makerspace.

“For the longest time I listened to people pitch me ideas. The biggest thing at the time was apps. People had all of these ideas for apps. But I wanted to get into something that really catered to Thailand’s strengths. So what is Thailand naturally good at? Thailand is exceptional with agriculture, manufacturing and tourism. Thais aren’t naturally good with the ideas of apps, or programming. We’re great with our hands and physical things, there are so many craftsman in Thailand that make these beautiful objects, but they need a place to expose them to more possibilities.”

Nati saw, and took inspiration from, the precision Thais had with their hands, while realising that there was a need for exposure to technology and ideas in order to inspire them to use their skills for innovation. “I’d see these beautiful carvings and things in the market, or I’d see the incredible skill of carpenters around the country, and I thought – ‘people need a place to make new things, to introduce things into this world’.”

Finding Bangkok to be an environment that was not only a factory for creating stress, but not conducive to fostering creativity, he decided on Chiang Mai. “To be creative you have to be happy. I think Chiang Mai is a place that is naturally creative, and a perfect place for Makerspace.”

Chiang Mai has an international reputation for being a city that fosters creativity. For some time it has been in the running to be nominated a Creative City by UNESCO, to be recognised as a “creative hub” and “socio-cultural cluster”. Just look at the regional handicrafts passed down for generations and the thriving contemporary arts community. And more recently, the creative community’s expansion beyond the traditional arts: do-it-yourselfers, designers, tech geeks and hobbyists of Chiang Mai have fully embraced the “maker” movement and put Chiang Mai on the international map of innovation. Just last month, Nati hosted an afterparty at Makerspace following the wildly successful Makerparty, a regional meeting of makers throughout Southeast Asia which attracted a whopping 500 attendees.

Makerspace, however, is in no way limited to self-professed geeks or computer programming majors, Nati is creating a community that is open to anyone, whether they’re a pro at creating digital 3D models or have never touched a computer before. Nati leads me over to a shelf where some more fabricated objects are displayed. He picks up a small 10 centimetre tall bust of a man.

“This is my first member, an artist from Switzerland. I started printing out models of my members. He wanted to learn how to use digital tools with his art. He’s a pen and pencil kind of guy, so we had to teach him how to use a computer.” He sets down the bust and picks up another, a man in a ball cap printed in pink plastic, “this was my next member, from San Francisco. Then I had a Thai student come in, she had an idea for a new chair that was all made of this honeycomb pattern. Now we have a Thai architect working here. He just signed up today, he wants to use 3D printing to take his designs that he usually can only work with on a computer and make them into real and tangible objects.”

The space is designed conceptually for anyone to walk in with zero knowledge and get to work. “At Makerspace we are a learning culture. We try to learn a lot of things but like to teach what we know. I know how to 3D print and I teach people how to 3D print and I don’t charge anything for it. But from there I expect them to teach other people around them, so it’s a way to pass it on and pay it forward. We’re here to teach each other, and in this way we can be a more highly innovative culture.”

This model, of being completely open and sharing knowledge, is the essence of the community that Nati is building physically and intellectually with Makerspace. All of the digital equipment is run on “open source” software, a term in the tech world that basically means the code is open to the public and can be modified as the end users see fit. It is the opposite of big name software companies like Apple and Microsoft that deliver a product that is on lock down. This “open source” idea, however, is present not only in the technology used at Makerspace, but is embodied by the members themselves. This method of sharing knowledge creates a community that can improve itself, fix itself, and be constantly innovating new ways of thinking and creating, much like they can improve, fix, or design new physical or digital tools. Nati is a sure exemplar of the open source mentality, sharing his skills and knowledge of technology and sharing his own projects excitedly. Nati is perhaps the most active “member” of Makerspace. He is an inventor, an entrepreneur, and a successful businessman that could have created a workshop all his own, but instead has capitalised on the immense value of community sharing.

At Makerspace, Nati has a few special projects in the works, patents-pending and all that, I’m told that I can’t disclose all of the exciting details, but the innovations that are now capable due to the increased accessibility of technologies like those housed at Makerspace are nothing short of remarkable. The first project Nati describes will revolutionise treatment for a medical ailment that has been ruining people’s lives since the dawn of man. The next project he describes, which I happily can share with our readers, is what Nati calls “The Internet of the Air, or IOTA.” The device is a hyper-local sensor and transmitter that constantly tweets data about the surrounding air quality. Nati already has one active and tweeting around Nimmanhaemin.

“With this thing you can just log on and see what the air quality is like. You can use it to check up on the neighbourhood you’re considering to send your kids for school, or you can check up on a park where you go jogging.”

“You see, with things like this you can bypass what has been the traditional manufacturing process. For example, I had this student when I was a professor at Thammasat University, and he had this brilliant idea for a pen for the blind. It was beautiful, it let people express themselves in ways that they never could before. But this was just a student, if he went to a manufacturer and was like ‘I have this idea’, they’d be like, ‘Great! Now give us $10,000 (around 325,000 baht) and we’ll give you 5,000 pieces, that’s our minimum order.’ But he was just at the beginning! He needed to test it, to adjust it, to correct mistakes and actually give it to blind people to use. Equipment like this and places like this allow people to do that, you can afford to take risks, you can be creative.”

“We’re entering into what I consider to be an ‘Industrial Revolution 2.0.,’ you know? I’m a dot com era guy, you remember the dot com era? It was an amazing time! People were finally figuring out what you could do with websites besides just look at them, you could sell things, you could design things through them. That sort of innovation is bleeding over into the physical world. If I have an idea I can come in here, I can print it out, I can cut it with a laser, I can carve it out of wood with the CNC machine, and these things are accessible to you and I, we’re not waiting for the big corporations to come out with something. I really think the next iPhone is going to come out of somebody’s basement.”

The printer comes to a halt. Our bunny is complete. Nati plucks it from the pane of glass and places it in my palm, still warm, “hot off the press as the say.” Yes, it’s a little plastic bunny, but one that is sending us down quite the progressive rabbit hole.