Nicole’s fingers hovered above the keyboard and a blank Google search awaited her inquiry. With a few keystrokes, the words ‘volunteer in Southeast Asia’ appeared into the search bar. She pressed enter, and within seconds, nearly 800,000 results popped in to view. Work with Orphans in Cambodia, one beckoned, while another told her to Build Homes in Bali! As a university student studying early education, the choice to volunteer as an English instructor was easy. A few short months later, she found herself boarding a plane from Michigan to Chiang Mai to teach at a Thai school for four weeks.

Nicole is a voluntourist: she came to Thailand to participate in community service while experiencing the culture, sights and smells of Chiang Mai. She, like many others, are part of an industry that has exploded in the past few years, with twentysomething Westerners flooding areas like Western Africa, Central America, and Southeast Asia to get the opportunity to travel and also contribute to the community. Nancy Gard McGehee, a tourism expert from Virginia Tech, estimates that there are approximately 10 million people every year who travel abroad to volunteer, and that number is ever-growing. All prospective volunteers have to do is apply to a volunteer agency with projects in their desired country, and the agency then sets up their placement at a host site. In theory, the concept sounds ideal: a community receives help that it needs, and a volunteer feels a sense of fulfillment while they travel. But as the popularity of voluntourism rises, so does the number of skeptics who are concerned these foreigners may be doing more harm than good.

Tourist Troubles

An increasing number of negatively slanted articles are being written that show a more troublesome side of volunteering. “A constant stream of volunteers to orphanages, showing affection to children and then leaving, disrupts the attachment process, and can leave children with many, many problems in their emotional and psychological development”, says Georgette Mulheir, the director of Lumos, a foundation to end child institutionalisation. It’s been proven that long-term support (typically over six months) is the most beneficial to kids’ growth and development. However, most voluntourists rarely stay that long.

In addition, stories have been unveiled of children being mistreated by organisations in order to get volunteers to pay money. Voluntourism is a profitable venture; according to the European Association for Tourism and Leisure Education who estimate that approximately 68 billion baht is spent per year by international volunteers. As a result, some areas of the industry have begun focusing more on profit than people. Data from UNICEF suggests that in Cambodia, 77% of ‘orphans’ cared for by voluntourists actually have at least one parent, most of whom gave their children up to an orphanage in hopes that they might get an education. In reality, to pull on the heart- and purse-strings of visiting foreigners, kids have been known to be starved, barred from school, and forced into closed and dirty quarters. The data also revealed that many of these orphanages spend only a third of their income from voluntourists on the children. Thus far, these greedy orphanages haven’t become popular in Thailand and are much more common in Indonesia and Cambodia. Still, reputable local volunteer agencies are quick to advise volunteers to steer clear of orphanages.

A recent article in Huffington Post warned of other ways volunteers can do more harm than good. In Tanzania, American volunteers had been helping to build a school. However, it was later found that local workers had to toil throughout the night to undo the volunteers’ sloppily laid bricks and then redo the proper construction, causing them more work, while saving face for the paying volunteers. In other cases, volunteers pay organisations to do construction work, in the process taking away jobs from local labourers and exacerbating the inequity of money distribution within a village. According to Mark Richie, who runs community-based tourism projects in Chiang Mai, “someone who is powerful in a village can become even more powerful because they monopolise tourism.”

On the other hand, research published on the effects of voluntourism in Chiang Mai by Nick Kontogeorgopoulos, a professor of International Political Economics, ultimately concluded that short-term volunteers in the city “are generally not there for long enough and are not doing anything so fundamental where they can have any deeply negative effect, with rare individual exceptions”. Of course, there are some instances of individual volunteers causing trouble — such as one teacher in Chiang Mai who had a relationship with someone at his placement and broke up a family — but these have mostly been observed as isolated incidents, and experts say little can be done to prevent them.

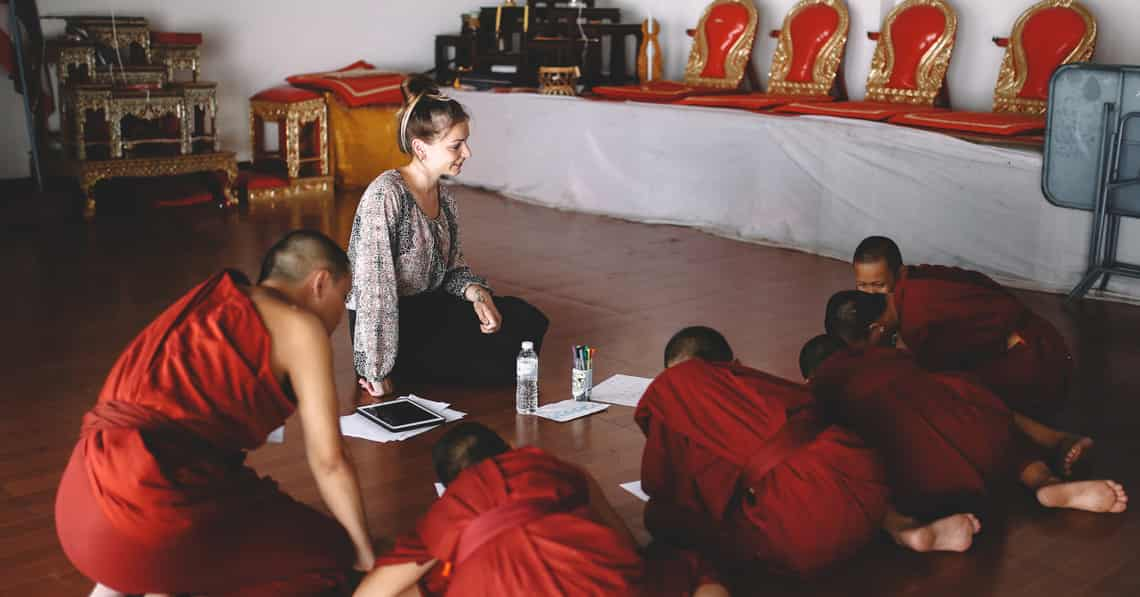

A group of raucous kindergarteners exploded into chaotic chatter when they saw Nicole enter the classroom. While these students already have a full-time English teacher and an assistant instructor, they rarely get the chance to learn from a native speaker. In fact, teaching and other specialised skills are some of the areas where voluntourism has had the most positive reviews. In addition, Nicole gets valuable experience in her future career path — experience that isn’t easy to come by in America. But with teaching, voluntourism is like candy: best in moderation. Instructors at the school where Nicole worked for a month attest that the students loved having her there. However, they also said that their director was wary of how many volunteers are brought on board because they already employ a number of full-time Thai English teachers. “They don’t have class to teach,” one third-grade teacher noted, “if we get a lot of volunteers. There’s not enough work to do.” One or two volunteers is ideal, added the teacher, commenting that it’s nice to get a break from classes every once in awhile.

The director of the agency that placed Nicole in her school understands the importance of moderation. In a sparsely decorated office a floor above where his locally employed staff works, he noted, “In terms of teaching and schools, certainly it would be a mess if there was no full-time English teacher and we just had volunteers coming through and they didn’t know what the last person was teaching, and that’s why we have our programme set where the volunteers are simply assisting the local full-time Thai English teachers.” As long as volunteers know they are working in assistance to the local community, voluntourism has in the past proven to be extremely beneficial.

Working as assistants, volunteers rarely have a large enough impact on the community to do any serious harm. However, they should still be wary of entering a country with the wrong mindset. As Kontogeorgopolous puts it, “Organisations need to continue to disabuse volunteers of the notion that they are there to ‘save Thailand.’ The focus should not be on development or ‘helping’ but rather learning about Thailand.” College-age students who come to Thailand searching to be a saviour of the poor by volunteering their meager skills are egregiously misguided.

Is There ‘A Right Way’?

Voluntourism’s rise has not come without some opposition. People are beginning to realise that what seems like a selfless, beneficial concept can actually be very detrimental if not executed properly.

“You need to have good screening. That’s the first step,” Ritchie explained. “Don’t just accept anybody who wants to come or anybody who’s willing to pay.” It’s tempting to capitalise on the naivet้ of volunteers to turn a profit, but it’s also really difficult for an organisation to create a good relationship with the community if volunteers aren’t carefully selected to ensure they are motivated enough.

“The second step is really good orientation,” according to Ritchie. Placing emphasis on the volunteer’s role as a learner through expectation management exercises is a great way to ensure they have the right mindset about what they are getting into. But the most effective way to minimise negative effects of voluntourism is to focus on the welfare of the community rather than the volunteers. The director of Nicole’s agency echoes a similar sentiment: the negative connotation surrounding voluntourism can be erased, he claims, “if organisations were certainly more interested in the benefit of the people being served, making sure that volunteers are coming in with the proper skills, that they’re coming in with the proper police criminal background checks.”

Unfortunately, not all organisations operate in this way. There’s also a certain responsibility on the volunteers to do their research before signing up. For a young adult like Nicole, browsing the internet for volunteer opportunities from thousands of miles away, it can be hard to tell if an organisation is operating sustainably. Ritchie suggests asking lots of questions, especially about where the money being paid is going, as a way to better understand the company’s motivations. In addition, volunteers should try to learn as much about the culture of the host country as possible so they aren’t fooled into doing something unethical that they’re made to believe is okay.

While pictures of Westerners surrounded by beaming children or outfitted with hard hats and work gloves seem noble, they may be hiding a darker truth. But voluntourism isn’t going away anytime soon — it’s an industry, and a profitable one too. As such, society’s primary focus shouldn’t be on if the industry should exist, but rather on how it should ethically operate.

In the future, careful certifications may mandate these organisations to follow certain regulations. For now, however, it’s hard to believe that the loud, cheerful students in Nicole’s classes are being hurt by a few songs and games.