“This is sacred land,” said Tior, who has resided in Nam Bor Noi since it was established decades ago. “This land belongs to Kru Ba Wong, the great monk whom we villagers worship from our core,” added Tior. “He taught us to follow Buddhist principles, be good people, eat vegetarian, not modernise, and maintain our culture. I want to preserve this.”

Nam Bor Noi, a fifty-three household 200-person ethnic Pakagayor (a.k.a. Karen) village community located in Lamphun Province, is a one-of-a-kind place. It is a community of devout Buddhists and strict vegetarians who exist essentially apart from the modern world. Those who live here use no electricity. Villagers utilise a hand-crank-operated bucket to draw water from holes they had manually tunnelled through the volcanic lava bedrock beneath their feet.

There is the occasional cackling of a battery-powered radio. There is the sound of wood being chopped. There is the hammering and grinding sounds from local handicrafts being forged. There are the footsteps of villagers, as they lug buckets of sloshing water across their shoulders. Muffled conversations coming from thatched bamboo homes with teakwood

leaf roofs can also be heard. Peeping birds flutter overhead; at day’s end, the birds’ songs are replaced with the chirping of jungle bugs.

“This village is very special,” said Tior. “It’s not just foreigners who want to observe our way of life. Other Karen villages need to see this as well. We want to teach others how to live like this. We want to preserve our way of life. This way of life is healthy. It’s something that money cannot buy.”

The reality

As utopian as it all sounds, life can be hard for villagers, as there are few avenues by which to earn a living.

Many villagers, versus living relatively sustainably with and from their surrounding environment, as they traditionally did, now must work paying jobs. This includes in urban areas, or by doing hard labour for private landowners and corporate agro-companies, for pittance.

From January until March, they hand-harvest corn and maize, collect leaves and grass for roofing materials, as well as dig lava rock that is largely used for construction purposes. April through June is Thailand’s dry season, so there is no agriculture; villagers clear land or do any kind of work that they can find. Some work various jobs in the city.

From July to November, villagers harvest longan, prune trees, tend gardens, dig lava rock, or plant rice. December is rice harvesting time. All hands on deck on land that does not belong to them.

While elements of their life may appear idyllic, there are always expenses such as the purchase of rice, lamp oil, clothing, toiletries, school uniforms and shoes. For a five-person family, total monthly expenditures average about 2,500 Thai baht (US$80). Some households can save between 1,000-5,000 baht (US$30-$150) per year, which they generally reserve for medical expenses.

While this may be their current reality, Nam Bor Noi (and other rural ethnic communities) is one of the few places remaining that if the electricity grid or the material supply chain feeding the modern industrialised world were to collapse, its community members, at least those equipped with traditional indigenous knowledge, could survive.

What is noticeably absent in the village are teenagers and youths; most of whom have left for larger towns and cities. Garbage has also become a new problem and can be seen along the village pathways and nearby roadways that used to be pristine and clean. And alarmingly, some Nam Bor Noi villagers exhibit signs of malnutrition.

“We are not suffering,” said Tior. “Living like this is fine. It is a quiet and peaceful life…Other people feel like they need material things to be satisfied in life. I think the most important thing for a happy life is to have my own space and food; I can survive. Having a car is a small thing compared to this.

“Eighty percent of the villagers living here in Nam Bor Noi don’t need (or want) electricity or running water,” added Tior. “If someone in this community has money and needs these, or if they don’t follow the rules (that prohibit modernisation), they can buy land elsewhere, build a house, and do whatever they want.”

Tior said that when all of us humans were born, we didn’t have anything; life was fine. But if we are greedy and selfish, it ruins our life and our relationships. “Our culture is becoming like this,” said Tior. “Actually, the natural world around us is just fine; people ruin themselves. Everyone should be a good person. I don’t know if I’m a good person. I’d like to know how to be one. I do know that I’m not greedy or selfish.”

Tior said the Thai government offered utilities and even solar cell technology to the villagers, but the village rejected electricity as a fire hazard.

“We asked the government about who would pay for the electricity, water and infrastructure repairs,” said Tior. “For me, I would like to have more light when I’m eating. But I am okay. A major challenge I face nowadays is finding roofing materials for my house. The climate has changed, and the grass is now hard to find. The leaves used as an alternative last only a couple years…

“I worry most about land ownership. I don’t have any rights to this land; the government owns it…If I don’t have land for growing rice, for eating, this is a big problem. Sometimes, there is no work. I worry about this too, and getting sick, but not too much.

“I want to transfer to my children what it feels like to live in the traditional way,” he added. “We (in Nam Bor Noi) support preserving this traditional way of life…We want to keep it special. We are preserving our way of life.”

Sacred land, sacred rituals

Every evening, many residents, including most of the children, congregate at the sacred well while dressed in their traditional clothing. They place offerings from nature and incense sticks to their revered late monk who founded this settlement forty-five years ago.

The congregation then turns around to face the temple, a kilometre away, where Kru Ba Wong’s embalmed body is displayed, before meditating en masse for fifteen minutes.

“There are many things with development that are surrounding us now. said Tior. “This nightly tradition is very important for our cultural protection.”

The seismic shift of development

‘Development’ is predominantly considered a positive thing. It is commonly linked with notions of ‘progress,’ particularly in the forms of modern necessities such as healthcare, financial security, mainstream education, and other aspects perceived as good for human well-being. This is coupled with technological innovations that make life easier and more physically comfortable. But what is development taking away from our cultures and our traditional ways of life? What are the societal replacements? What are the short and potential long-term impacts? What does this mean for all us humans?

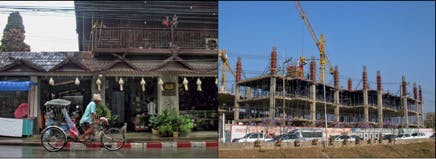

The rapid development of Chiang Mai city, located in Thailand’s North and considered this country’s second capital, over the past few decades has, for example, dramatically altered its traditionally slow-paced and conservative culture into a mini-Bangkok metropolis. This is particularly evident with worsening traffic congestion, pollution, and increasing social tensions.

What can also be observed is shifting demographics including regional migration issues, societal homogenisation involving the national acculturation of indigenous ethnic peoples, expanding income inequality and additional societal stratification, competition for space, and other unplanned changes.

Some rural populations here still function in a similar fashion to before the prominent onset of urbanization. However, this is rapidly changing. The global market system, and various lifestyles associated with the modern world, is perforating their social fabric. Homogenising ‘modern world’ culture is replacing ethnically traditional lifestyles. This is effecting everyone, including those living in remote rural areas.

Northern Thailand’s ‘highlanders’

Thailand has ten officially recognised ‘indigenous’ ethnic groups. They are the Karen, Hmong, Akha, Lisu, Lahu, H’tin, Khmu, Lua, Mien, and Mlabri, totaling over 926,000 people, according to the Asia Pacific Human Rights Information Centre and Network of Indigenous Peoples in Thailand.

Commonly referred to as ‘hill tribes,’ although ‘highlanders,’ as a more politically correct term, is taking root, these ethnic groups are some of Thailand’s most marginalised of the marginalised.

The Thai government has been campaigning to reject the term ‘indigenous peoples,’ as part of its decades-old ‘Thai’ national cultural building campaign (e.g., the “12 Culture Mandates”). The reality is that Thailand’s ethnic peoples continue to endure the same historical stereotyping and systematic discrimination as indigenous peoples elsewhere in the world. Although many of these communities have for generations lived in northern Thailand’s mountains, many are still not considered Thai nationals. Therefore, some do not have Thai citizenship necessary for receiving government social benefits, among a multitude of other issues.

These groups have also been forced, through public policy, to become part of the aforementioned modernising trend. This is increasing their dependence on local and world market systems traditionally alien to them for survival. For the most part, villagers can no longer live in their traditional manners. This overall situation is having a profound impact on their ways of life, making their future uncertain.

Territorialisation of land and culture

The Thai government implemented land use regulations in the 1950s by officially considering, therefore placing, rural ethnic communities inside national park ‘reserved forest’ territory. This rural development scheme essentially corralled previously independent mountain villagers into a top-down State control system that determines how they earn a living.

For example, their traditional slash and burn shift cultivation practices, central to their traditional livelihoods, were banned. This may appear to some as a minor inconvenience; however, if viewed through a social-ecological lens, the entirety of villagers’ lives (e.g., livelihood, textiles, language, music, oral traditions etc.) traditionally revolves around the harvest cycle. If these socio-cultural systems become interrupted (or severed), as they did in northern Thailand, a situation ensues whereby people are rendered essentially in an identity crisis of sorts, until another system can be structured and implemented (if at all).

Essentially, they were arguably force-converted to farmers of sedentary orchard agriculture. Forest products, regarded by some village communities as common pool resources, are no longer legally theirs for harvesting.

In 1961, the Thai State Park Act was ratified. This policy instituted the further establishment of national parks and other forest conservation areas, all managed by the strict authority of the Royal Forestry Department. This brought with it a plethora of further major changes for rural highland communities. This included stringent land use regulations effecting villagers’ traditional practices involving hunting, fishing, as well as wood, medicine, and forest food gathering.

For animist agrarian societies with animist spiritual beliefs, all of these traditional practices are vitally linked with their belief systems. If these societal systems are drastically altered or severed, a form of irreversible ethnocide ensues.

A social-ecological transformation for highlanders

Overall, the villagers appear to be in shock, desperately trying to maintain their traditions while adapting to the encroachment of a modern lifestyle that is pulling them in, particularly the youth, one television programme at a time. For many villagers it’s as though they’re simultaneously living fundamentally different ways of life — a mixture between their cultural heritage and that of the mainstream modern world.

Roots of transformation

Placing this further into the context of Nam Bor Noi village, Tior’s community is encompassed by nine other Karen villages; they all constitute a lowland Karen settlement area called, Phabat Huaytom. Its total population of about 13,000 people. Like its surrounding lowlands and urban Thailand counterparts, is as well underway to succumbing its traditional culture to a modernising trend. This is transforming ways in which they interact with each other and with their surrounding environment.

Tior said that in the early 1970s there were four Karen elders who were seeking “a healthier way of life” away from hardship and opium addiction. They held Kru Ba Wong’s Buddhist teachings in high esteem and pioneered a new path by pilgrimaging from the highlands to Phabat Huaytom in order to learn from the sage.

“Nearly fifty years ago, I lived high in the mountains,” said Kabuwa, 84, one of these four pioneers, from a hut-like structure placed in the middle of a watery and verdant rice field. “My life wasn’t comfortable. The transportation wasn’t good. I had to walk on the steep and mountainous slopes, go up and down. It wasn’t good. But it was easy to hunt and find wild food.

“I was inspired to change my lifestyle for Kru Ba Wong, the great Buddhist monk who visited my village many times,” added Kabuwa. “He brought with him many wise teachings. He taught about the Buddhist code of ethics and the five precepts.”

When Kabuwa arrived to Phabat Huaytom, there were only two houses built. Soon after his arrival, however, many Karen began migrating here. Infrastructural development had also expanded.

“We all came here to follow Kru Ba Wong, to make merit, to follow his teachings,” said Kabuwa. “When I moved here, there was abundant shading from large trees, unlike nowadays,” he said. “The houses were constructed of bamboo and grass, Karen style…Everyone lived in harmony. We were sharing, not selling things like we do today.”

Back to the basics

Just thirty years ago, all villagers in Phabat Huaytom still lived traditionally like those in Nam Bor Noi. This livelihood, including in Nam Bor Noi, has near totally vanished.

“In the past, we had no modern technology,” said Kabuwa. “We hand-washed our clothing. We used organic materials such as roots and charcoal to clean our teeth. All of our food was cooked using a wood-fueled fire, and we used candles for lighting our homes. We walked everywhere. Only the wealthier people could afford a bicycle. Still, everyone was in-harmony, unlike nowadays…Everything has to be purchased now. People are more selfish, and they buy more things.”

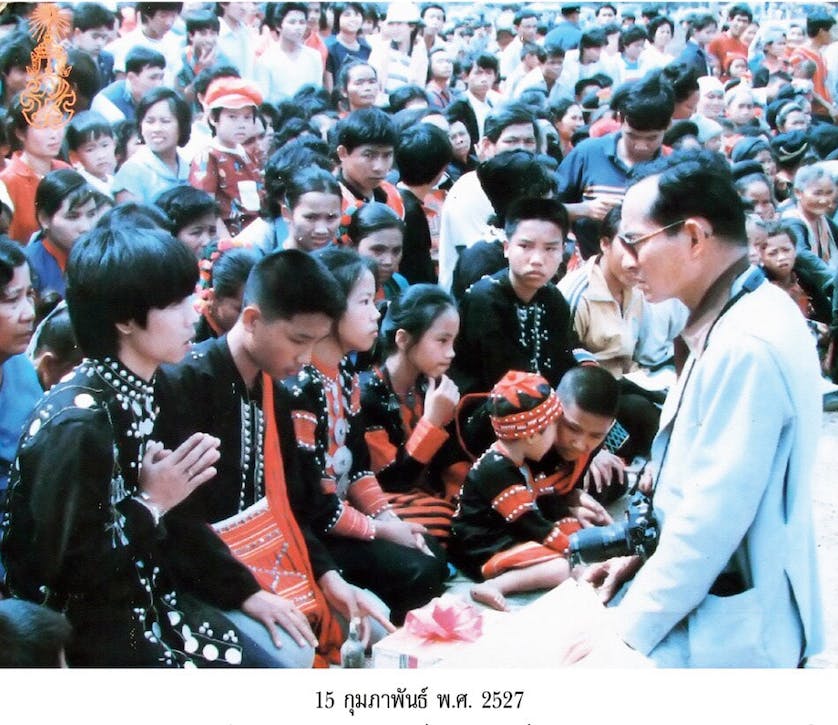

Kabuwa revealed that things really began to change here about ten years ago when the road was changed from dirt to tar. “This brought the outside world to us even more,” explained Kabuwa. “In some ways, things did change for the better after Kru Ba Wong asked the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) to bring in academics here to teach us what plants were best suited.”

The King also agreed to Kru Ba Wong’s request to have all villagers abstain from being drafted into the military, due to its their strict Buddhist beliefs. His Majesty also helped develop reservoir and irrigation projects which, for the past twelve years, has allowed the village to begin to grow rice.

“There used to be one man here who could teach Karen writing, but now he is blind,” said Kabuwa. “We proposed these teachings be part of the curriculum offered in the local Thai school. However, this idea was rejected. We were told that if we are to be Thai then we must learn Thai. We are not Thai!”

What can be done to preserve these ways of life?

“Nowadays, we can and do maintain the traditional Karen ways of life,” said Kabuwa. “We still, for the most part, keep the Buddhist precepts. We still speak Karen with each other. We still weave and often wear our traditional clothing. Our houses still have no fences around them; we welcome our neighbors. We aren’t forcing anyone living here to do this. Everyone is doing it by himself or herself. I believe that by people staying together like this, we can keep ourselves together through community connection.”

Tior admitted he also does not expect that the newer generations will preserve this culture. “However, once you’ve been in this environment, it will be with you forever,” said Tior. “Because the younger generations here have lived like this, it will be with them forever…If we take care of our children, equip them, then we will protect our culture.”

Kabuwa was asked if he had a specific message that he wanted to share with the world.

“I don’t know how much longer I will be alive,” said Kabuwa. “I don’t know what will happen here once I am gone. I don’t know if their lives will have more suffering, how much they will be so busy. It’s not like in the past. I know I feel sad, if they don’t keep a simple life like in the past.

“I want the Karen to come back and keep our traditional ways of life,” he added. “Don’t leave it! Don’t see capitalism, the outside, as more important than our traditional ways of life! Our way of life is simple, not busy like those people in the city. Keep the good relationships that we have with each other.

“I want to say to the Karen people that if you have lost your way, please come back.”

Jeffrey Warner is a civil journalist and documentarian-storyteller, who focuses primarily on capitalism development impacts, social change patterns, and building social capital. Jeffrey has for about a decade been living in Chiang Mai, where he’s been documenting how some of the region’s marginalised people (particularly Burmese refugees and ethnic indigenous communities) are being impacted by development phenomena. Jeffrey’s website is www.jeffsjournalism.com.

Special thanks goes to Tanya Promburom, for making this article possible by facilitating village visits, and for translating.