A few kilometres north of Chiang Mai, adjacent to a stretch of otherwise uninterrupted highway, sits a housing development. Driving forth from the city, darkened fields emerge to flank the road, replacing the receding urban iridescence. A freshly lined road leads up to a gatehouse; the uniformed guard peers out from within. Sinuous Thai characters affixed to a massive sign declare the development’s name. Trimmed hedges accessorise, towering palms sprout throughout, and scattered spotlights illuminate everything dramatically. The image is one of near-celebrity elegance -indeed, the entrance recalls that of a Hollywood movie studio.

Within, the scene is just as much one of modern refinement. Immaculate lawns give way to identical two-story homes; quaint lampposts referencing Victorian England cast warm light on paved sidewalks; mailboxes punctuate each driveway. We pass a lone golf cart parked on the street. One would be forgiven for mistaking this place for the gated community of some American metropolitan suburb; it is, in many ways, the perfect imitation of suburban American affluence.

This story, though, is not one about Thailand’s decidedly emergent middle class. It is, rather, the story of the foundation upon which that middle-class rests, figuratively and, in a way, literally. Because if you continue far enough down the winding roads of this queer homage to western habitation, the pavement will turn to dirt and rock the lampposts replaced by the white glare of fluorescent bar-bulbs, the stucco walls transformed into corrugated tin. Here, not a hundred metres from the hollow structure of yet another house under construction, is the camp where the migrant workers responsible for building that very house and every other one like it make their own homes.

I have been to a number of similar developments in the Chiang Mai area, though they exist everywhere across Thailand. More often than not, I have arrived at these developments with the express purpose of visiting the attached settlement of construction workers, usually migrants from Burma. And on each occasion, I have sat through the sudden transition from suburban idyll to seeming squalor.

The juxtaposition is always jarring. Inequality persists everywhere in the world, and is expectedly pronounced in developing or recently developed nations. But the proximity of the two extremes on display here renders this iteration especially disquieting. The change is so abrupt and the two situations so dramatically disparate that you would be forgiven for thinking it almost fantastical: an absurdist’s interpretation of social commentary, a collaboration between Dickens and Kafka.

This camp (referred to by many in Thai as a moobahn rang-gnaan, roughly “labour village”) is composed of approximately two hundred Shan-Burmese migrants. In Chiang Mai province, the majority of Burmese migrants are of ethnic Shan origin, and a sizable portion of those are employed in manual labour, often construction. This camp has been their home for close to a decade.

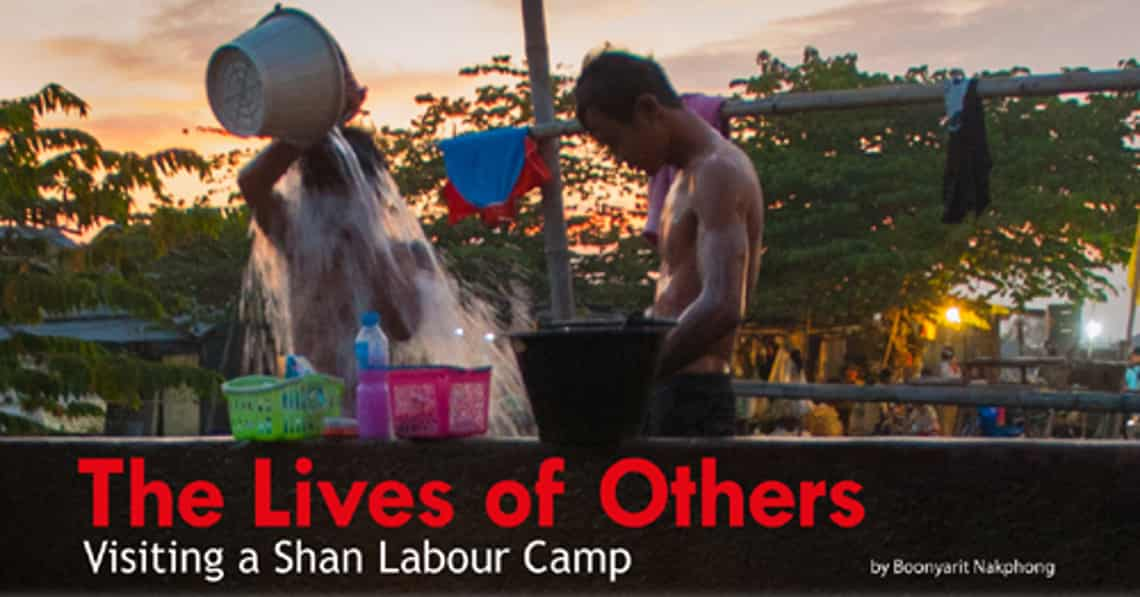

At first glance, conditions in the camp are sparse. Single or double-room shacks, structures improvised from sheet-metal and an assortment of wood parts, sit precariously a few feet off the ground. In the early evening, workers stand on the periphery of an enormous concrete basin full of water, bathing. In a far corner of the camp sits a small hut designated as a communal latrine. During periods of heavy rain, the camp floods. On the other hand, the amenities of modern living also make an appearance: televisions are in abundance and, while passing an open door, I even glimpsed a desktop computer.

During this last visit, I sat for a lengthy conversation with half a dozen migrants who live in the camp. I came with the ostensible intention of discussing the recent developments in Burma with some residents of the camp, and whether those developments had inspired any interest in returning home. The answer, it turns out, is mostly no (though as the conversation drew on, I became less and less interested in pursuing that question). I realise retrospectively that this should come as no surprise.

The changes in Burma over the last year have been welcomed with enthusiasm by the global community. In particular, the reemergence of the Burmese economy, for so many decades crippled by the lethal coupling of internal mismanagement and international sanctions, has led to an optimistic projection of Burma’s rise from poverty (Burma has long been ranked among the poorest countries in the world). And while this may soon prove true, the fact is that this forecasted growth is precisely that: forecasted. Real economic opportunity remains scarce.

One young man I talked to had arrived in the camp the day before to visit a relative. He came from Rayong province, where he is employed in a factory that manufactures auto parts. When I asked whether he thought he might return to Shan State in the near future, he looked at me quizzically, as if he had not quite understood the question. He went on to explain that while he would like to one day return, it simply made no sense to do so now: the work in Thailand paid better, and – he was confident – would continue to pay better, at least over the next few years. The others seemed to concur. All of the men and women I interviewed were making close to 300 baht even before the new minimum wage was enacted earlier this month. They seemed to approach the matter using a simple calculus: though each was clearly interested in returning to Shan State, where many still had family, the financial incentive to continue to work in Thailand was still too convincing. Unprompted, that same man from Rayong province launched into gushing praise of the overtime (and overtime wages) that had recently become available at his factory.

The plight of Burmese migrant workers in Thailand has not gone undocumented. Stories of abuse and exploitation appear regularly in both regional and international publications. These stories have arguably increased in frequency over the last year as the global community has begun to refocus on a newly democratising Burma. The living situation for Burmese migrants in Thailand has long been precarious, to be sure. But speak to the migrant workers themselves (at least the Shan here in this camp), and you begin to see the nuance of the picture.

When asked about the difficulties faced by Burmese migrants in Thailand, most of those I interviewed seemed intent on diverting from the usual narrative of abuse and exploitation. They pushed back against the media-driven model that has them fixed in the role of victim. Many of the Burmese in Thailand qualify as refugees _ fleeing systematic persecution, they have crossed the border in search of a safe haven. Many others, though, are economic migrants, working in Thailand because it is profitable to do so. I reminded the group that a year earlier, I had accompanied a group of migrant worker activists to that very same camp to observe them giving an educational presentation on registration. At the time, I had noted the urgency with which the crowd of camp residents had attended the presentation. At the mention of this, the men and women I was speaking to readily agreed that the registration process for migrant workers was in many ways flawed or inadequate. But even this concession was delivered with shrugging disinterest. The consensus was that they were doing alright. They worked hard, to be sure, but also expressed something verging on gratitude for what they perceived as worthwhile recompense.

Of course, the truth is that there exist Burmese migrant workers across the country who are far less fortunate. Unlike the men and women in the camp, many (perhaps the majority) do not have regular access to healthcare, nor schools that will accept their children, and can only dream of a reasonably-houred work day with a fair wage. Others are victims of trafficking or other forms of labor-bondage. And, despite the great progress that migration policy and labour law have made in the last decade, old problems continue to persist while new problems emerge: the registration process for migrant workers is indeed flawed, and reports have come forth that the new minimum wage law has prompted the reduction of low-paying jobs that would otherwise be occupied by Burmese workers. Nevertheless, there also exists a selection of the Burmese migrant worker population for whom the situation is not so dire.

A year ago, while in Mahachai, I met a 20 year-old Mon-Burmese construction worker who wept profusely as he tried in broken Thai to detail the suffering he was enduring: impossibly long hours at physically depleting work, an abusive boss who often withheld already truncated wages, the constant threat of termination or deportation. I had never seen a desperation quite so arresting, and have not forgotten it since.

Perhaps in part because of that, I have never been able to shake my discomfort at the contrast detailed in the opening paragraphs of this piece. As a labour advocate, that contrast for a long time perfectly reaffirmed my own conception of the haves-versus-have-nots dynamic, one class prospering at the toil of another. I often return to reassess the validity of that model. At times, it feels grossly simplistic; this is a begrudging admission. The parade of articles lamenting the hardships of Burmese migrants in Thailand gives an incomplete understanding of the situation, as my conversation at the camp reminded me.

And yet, there is a construction worker in Mahachai whom I still have not forgotten.