Text and graphics by Anna Brooks

It balloons out at you from strategically placed billboards around town. You vehemently nod along, pretending to know the ins and outs of it at a supercilious dinner party where the pompous try to one-up each other. News outlets have been shouting out its every move like sportscasters on crack.

ASEAN, more lengthily known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is the hot topic du jour. Having just celebrated its 45th anniversary, expectations (and apprehensions) are high for the quickly approaching future of ASEAN countries. By 2015, it will be official: Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines are tying the knot, all marrying into another packed acronym, the AEC (ASEAN Economic Community).

Regardless of what could be classified as “looking forward” and tenacious terms like acceleration, integration and synergy saturating ASEAN blueprints, adverts and speeches, the “ASEAN effect” seems to be similar to the iceberg’s; how many of the 600 million occupants of ASEAN territory only see the tip, a tip which is laced with gleaming smiles, smiles that promise the kind of growth and prosperity that only togetherness can bring.

What’s beneath the tip are words that have gone from floating around like daydreams to solidifying into reality – economic amalgamation, stable infrastructures, free flow of goods, services, labour and capital…

As most admittedly arduous missions are, the positives are extensively (and predominantly) displayed, as if by doing so what is advertised – economic growth, higher wages, equalisation of wealth and disparity – will ensue. While the future does sound rosy, there are many thorns to be wary of, thorns representing what could ensue.

Ahh it’s Godzilla! Oh wait, it’s China…

Thorns aside, exciting things are on the horizon for Southeast Asia. Reiterating goals outlined in ASEAN’s blueprints, the organisation’s plan to “bridge cultural gaps” should, in theory, tear down language barriers, open up job opportunities and cement the ideal that “when we are one, we are stronger.”

According to Christopher Dent, professor of East Asia’s International Political Economy at the University of Leeds, “ASEAN is arguably one of the most successful developing country regional organisations in the world.” He says this despite speculations that ASEAN runs the risk of meeting a similar foreign policy fate to the European Union (EU), which, a “secret columnist” at Public Service Europe joked, “doesn’t seem to know its elbow from its other anatomical parts.”

But “ASEAN has a wide range of programmes for advancing regional cooperation in Southeast Asia, and in some areas they have achieved considerable success, especially on economic cooperation,” Dent explained. “We should not compare its achievements to the EU, but rather to other, more relatable developing country regions.”

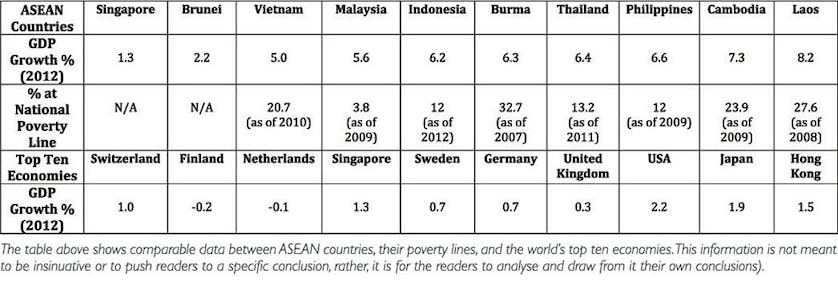

While it should be a relief that ASEAN and the EU aren’t likely to become economically synonymous (well, hopefully not), a developing region’s progression is a delicate web, one in which the disintegration of a few weak strands can leave the whole devastated. In order to better understand, the following table outlines some important albeit slightly boring information (when are statistics ever exciting?) juxtaposing individual GDPs (gross domestic products) and poverty lines.

Although business gurus would heatedly argue either for or against GDPs being an accurate measure of the growth of a country’s economy, numbers sometimes say more than words. Economic analyst and business strategist Kim Amadeo said that while most would assume the higher the GDP the better, in actuality, high numbers could represent an “asset bubble.” The danger with an asset bubble (as is the case with any type of bubble) is sudden, and usually undesirable, popping.

“I think developing countries can safely sustain faster growth rates without incurring too much inflation because they’re quickly trying to raise the standard of living for their people and build infrastructure,” Amadeo said. “That being said, they still have to be careful – Cambodia’s inflation rate was 5.5 percent last year [or 7.3 percent, according to data from The World Bank]. It’s a difficult balancing act.”

Additionally, busty GDPs do not necessarily ensure the levelling out of wealth and disparity; Amadeo added, “in some nations, the GDP is dispersed among a small, elite class, leaving the rest of the nation in poverty.”

No country is exempt from worrying about their GDPs, FDIs, LOLs (just kidding) and innumerable other confusing acronymic measures of an economy’s vitality. But while ASEAN economies do have to be careful not to burst their financial bubbles, a more pressing problem looms: China.

While it’s been addressed numerous times by more scrupulous media outlets such as the New York Times and TIME Magazine, China’s clever puppeteering of its “economic empire” is worrisome for budding organisations such as ASEAN that are comprised of resource-rich countries ripe for the exploiting (except for you, Singapore).

Although, according to information outlined by the Department of Trade and Industry, the “ASEAN-China Free Trade Agreement will enable regions to enjoy improved market access, growth in commercial presence and higher levels on investment,” the fact that it is “the largest free trade area in terms of population” means that (while merely speculating, keep in mind), it could provide a wider stage for Chinese control of locations, markets and resources.

David Roland-Holst, professor of Economics at University of California at Berkeley, said that “enormous economic forces” like China are appealing to ASEAN countries because of mouth-watering prospects for ASEAN exporting and investments. Roland-Holst also mentioned that while ASEAN is “fascinated by China and the opportunities it presents, it is also terrified because China is so powerful.”

“China plays its part very strategically,” Roland-Holst explained. “ASEAN’s susceptible to being divided and conquered; because of ASEAN’s weak unification, it’s vulnerable to being exploited by China. China will try and negotiate with each ASEAN country individually on the basis that’s most advantageous to them.”

So, while diverse economies are said to strengthen ASEAN’s backbone when it comes to long-term goals of eradicating inequality between countries like Burma and Singapore as well as providing “a reason for specialisation,” how can ASEAN better moat itself against (while still managing to do cooperative business with) superpowers like China?

“We’ve seen this with Europe too,” Roland-Holst continued. “China had a way of dividing Europe because it’s much easier to trade with individual countries. Now China’s come along and essentially said to ASEAN, we want your resources, but we don’t really care about your labour forces or manufacturers.”

Click on the table to zoom.

Ready the troops, Chiang Mai!

Let’s put China on the backburner for a moment to celebrate the good news: You don’t live in Burma where ethnic minorities are still facing genocide by extremists, or in Laos where almost 30% of the population is (according to The World Bank) at the national poverty line. You happen to be lucky enough to live in Chiang Mai, “the Rose of Northern Thailand,” the city recently rated by multiple different sources as one of the top ten places in the world to live.

Despite such a glorious fact, flourishing cities like Chiang Mai will still have to undergo serious adaptations to prepare for the arrival of the AEC in 2015. To name only a few of the fastest coming changes: ASEAN mobile phone apps that translate 11 different languages (the most crucial of the 11, of course, being English), a diverse mass influx of foreigner workers and tourists, higher wages, a swell in job opportunities, intense technological advancements, and…I’m out of breath.

While these changes are expected by most and thus shouldn’t be surprising, residents of Chiang Mai should also prepare for the unexpected – the inevitable suffering of the unadaptable. If shortages of skilled workers continue to rise while immigrants with special skills (i.e. advanced English speaking and/or technological skills) start to better fit the bill, what will happen to the Thai population? Sure, there is to be an expansion of the job market with the onset of the AEC, but if locals cannot get a job in Thailand, where will they work?

Sorapob Chuadamrong, the vice president of the Chiang Mai Chamber of Commerce, said that while “nowadays everyone is thrilled with ASEAN” and by 2015 liberalisation amongst ASEAN countries “should occur in full,” it is not irrational to fear that even thriving cities like Chiang Mai “could be left behind as the rest of the world continues to develop.”

“I would recommend to the people of Thailand, especially Chiang Mai people, to develop professional skills of their own,” Sorapob said. “English skills and the use of technology and computers will be foundational to getting any job. But, equally as important is diligence, patience and discipline.”

Even though Sorapob has had healthy relations working with Chinese business associates for years (he can even speak Chinese!), he was not afraid to comment on the hazards of countries like Thailand working with China. He explained that China is extremely tactful in terms of business strategies, and ASEAN members should carefully assess the trustworthiness of transactions with the Chinese before diving headlong into tempting propositions.

“The benefits and dangers of working with China are equal,” Sorapob cautioned. “Urgent changes must be made to ensure the people of Thailand become winners in the global race, or at least, survivors. Otherwise, we will become destitute. Thai people that don’t adapt when the time comes run the risk of expulsion from society.”

While all this may sound like grandiose pessimism, it’s only meant to get people thinking. It’s a bit like getting ready for battle (without steeds, swords and bloodshed, of course): the more moves you anticipate, the better your own strategies become, thus the more likely you are to win (I know, I know, it’s about equality, not winning).

To conclude and perhaps clarify, this article is not meant to purport anti-ASEAN ideals nor encourage blissfully naïve expectations for a perfect “one identity, one vision” ASEAN nation. It does not (and cannot, in only a few pages) fully examine or explain the throng of multi-faceted ASEAN pros and cons. There are a myriad of other goals and holes equally as critical to be addressed, but alas, the ASEAN ocean is just too deep.

As I am not an expert in business, economics or political science, it is not my place to advise regional organisations and residents alike how to best prepare for change, or to accurately predict what said changes could even be. But after research, conversations with ASEAN-savvy sources and scholars alike, the only sound advice I can leave off with is this: whether rain brings flowers or floods, the best thing anyone can do is bring an umbrella.