So, how easy is it to become a teacher in Thailand? Very easy, as Fry’s article demonstrates. But her story says more than that: staying in the classroom _ and actually being able to teach – is an entirely different ball game. Even if Fry had wanted to teach, she wouldn’t have been able to.

With barely any preparation from her school, Fry had absolutely no knowledge of the school’s rules, conduct, or grading policy before she began teaching. Classroom conditions were abysmal. In one instance, she describes struggling to get students to write their own, original sentences, and, after barely accomplishing that, watching students blatantly copying answers from each other: “Cheating – or students doing one another’s work happened in every class, and was done in the blatant, undisguised manner of something routine. When I scolded against it, students were baffled, and then quickly resumed writing the other person’s paper.” Fry taught for only four days before calling it quits – a resignation that seemed of little concern to the school administrator.

Fry’s story should not be mistaken as just another rehashing of the debate over unqualified teachers in Thailand. As much as it reveals the ease with which one can slip in and out of the education system, it’s also indicative of the major problems dogging English teaching in Thailand today _ problems which find their roots in an archaic system of rote-learning, lacklustre commitment from teachers, and inadequate accountability among teachers and administrators. They continue to impede improvement in a country where English proficiency levels are already among the lowest in the world: a recent World Competitiveness Report from the International Institute for Management Development (IMD) ranked Thailand 54th out of 56 countries for English proficiency, the second-lowest in Asia. Despite the fact that the Thai government has consistently devoted around 20% of its national budget to education, Thailand has shown almost no significant progress since 2003, while other countries in the region soar ahead.

With the upcoming ASEAN Economic Community in 2015, the pressure to improve English proficiency has never been stronger. As masters of the so-coveted tongue, native English-speaking teachers have the potential to play a much-needed role in bringing the nation up to standard. But in a bureaucratic education system that undervalues its teachers, fails to challenge its students, and provides little to no support for its employees, foreign educators often find themselves trying to teach, but not being able to do so. Furthermore, cultural differences play a role: as a foreigner, the experience of being a teacher inevitably involves grappling with Thai culture – one that is not necessarily the most welcoming to outsiders. Taken together, teaching, no matter one’s qualifications or experience, is a challenging task.

How we learn

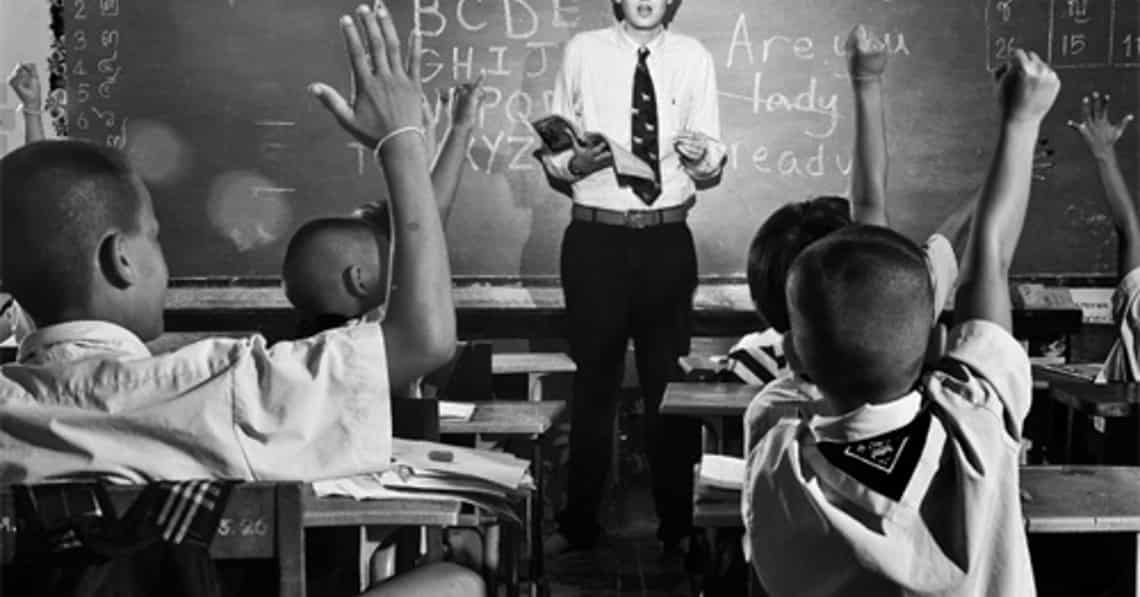

Many teachers will be overwhelmed by the dynamics of a Thai classroom, where large class sizes, a wide range of skill levels among students, and, most importantly, a lack of a real understanding of English, makes teaching difficult. Classes regularly hold up to fifty (and even sixty) students, and new teachers will be lucky to get a quick glance at the syllabus before they’re flung into the classroom. Yet perhaps one of the most significant obstacles to English proficiency is Thailand’s rote-learning system, which emphasises memorisation and continuous test-taking. Many western educators, as well as Thai students themselves, have stressed that this system is one in which a mechanical mode of learning has made students passive and uncritical. Language acquisition becomes especially difficult, as students spend years of their education being given the same grammar worksheets again and again, without the opportunity to hone their listening or speaking skills.

“We’re looking at an educational system that was designed for a different era than the 21st century,” said Jack C. Neale, coordinator of international affairs at Prince Royal’s College, a private Thai school. “And that’s where we have that difference in compatibility with Thailand and the rest of the world.”

“A language must be mastered through use, through doing,” he continued. “Yet we teach English as a rote-learning, academic subject. We teach it as a grammar-based subject…and it’s taught that way because many Thai teachers don’t know how to use English themselves, so teaching it as an academic subject is easy. ‘These are the rules, I can give them a worksheet, etc.’ But what happens is that students come into Matthayom not being able to write a basic sentence.”

Tong, a PRC graduate who attends university in the U.S., said that he learned most of his English outside of class. “The only thing we learn in class is grammar, grammar, grammar, all the way through. The teachers just give you a list of vocabulary and tell you to memorise it. But it’s more about being exposed to the actual usage,” he said.

The result is that students don’t know how to use the words they learned, instead focusing on knowing just enough for tests. “If you sit in a Thai classroom, you would think you were in a cram school. Because most of what we learn is copying down lectures, studying them, and remembering them for the test,” said Tong.

But for all the talk of tests and national exams, here’s a glaring contradiction: an unwritten, but ubiquitous rule in Thai schools is that students cannot fail their classes.

“The students have to pass, there is no failing,” explained one English teacher at a private school. “If they fail the test, you’re supposed to give them some extra homework, and that means they automatically get 50%. The school doesn’t hold them back a year, no matter how bad the students are.”

A classroom environment in which students seldom experience academic failure, or suffer the consequences of doing so, can also lead to a culture of unmotivated, complacent students. When the default grade is a pass, some students feel no need to work. “When I gave bad grades, students would accuse me of being mean and cruel, or stressing them out – even when they were the ones barely showing up to class and not doing any work,” said one former university English teacher.

Cheating and plagiarism were also endemic, with little consequence. A number of teachers recalled being approached by students with papers, and even university theses, and being asked to ‘edit’ the work, with ‘edit’ often meaning ‘rewrite.’ If Erika Fry’s name sounds familiar, for instance, it’s because she was the Bangkok Post reporter who was forced to leave the country after exposing a top government official’s plagiarised thesis.

Cheating has more than just the immediate consequences of one person lying their way to success _ done often enough, the practice becomes entrenched in the culture. An op-ed in the Bangkok Post commented on the proliferation of degrees and certificates on sale: “Pay to pass is old news,” the author, a lecturer at a university, wrote. “Hiring a ghost writer to complete a thesis is common, so is the straight-up purchase of a degree. It’s the same old story.”

However, the author also pointed out that it wasn’t necessarily the students that began the process; parents were the ones that opted to buy the degrees. “A typical classroom is simply a mirror-image of the society at large,” the author wrote. Students were merely following the examples of those that came before them, and weren’t always to be blamed.

A number of teachers expressed similar sentiments: students weren’t always to be blamed. They just weren’t in a system that taught them any better.

“We have a lot of children that are not meeting their full potential because of the educational system they are in,” said Neale. “I think Thai students, intellectually, can compete with any student in the world. It’s the educational system that’s keeping the students down.”

Yet even if educators make changes within the classroom, other problems await outside it. “Teachers are in a system where they are undervalued, and especially for foreign teachers, made to feel expendable.” Foreigners also find that the problems of integration and culturally differences factor into how well they can teach.

The politics of being a teacher

For both Thai and foreign teachers, salaries are low to begin with. However, a two-tiered salary system can be a source of tension and resentment between Thai and foreign teachers. Because Thai law decrees that foreign teachers must be paid more than Thais, starting salaries for a Thai teacher can be as low as 7,000 baht, while those of native-English speakers hover at around 30-35,000 baht.

For some, this is a cut-and-dry situation: “You have a Thai teacher who can’t speak English, and you have a native English speaker who can. Who do you pay more?” asked one teacher. Many foreign teachers have pointed out that while their pay is considerably higher, they lack the support networks that most Thais have.

On the other hand, the fact that a recent education reform act included a stipulation for teacher debt highlights the extent to which Thai teachers are underpaid. Most Thai teachers must resort to teaching extra classes to supplement their incomes, which oftentimes detracts from their classroom commitment. It’s a sign that in both cases, the government is providing very little incentive for teachers to get qualified, or to teach well.

The disparity in wages is also an example of the ways in which foreigners are systematically made to feel like outsiders in the education system. While this particular requirement may seem a privilege for foreigners, other grievances lower the scale. Foreign teachers, including university professors, are not allowed tenure contracts, instead being hired on a yearly basis.

“It’s like a kick in the face,” said one teacher at a private school. “It’s as if the school was saying – we might not want you next year.”

And for every foreigner, there’s always the risk of having to leave the country. Even with a work-permit and a two to three-year contract, foreigners still must renew their visas every year. “There’s no stability for a foreigner here,” said another teacher. “The law might change, and you lose everything.”

The disparities in the way Thai and foreign teachers are treated begs the question of just how much Thai educators are willing to integrate foreigners into the education system. “As much as Thais emphasise learning English from native speakers, there’s still an overwhelming sentiment that foreigners just don’t fit.”

“The Thai teachers and the foreign teachers don’t mix,” said one teacher at a private school in Chiang Mai. “We are treated as a collective unit; so if someone does something wrong, it’s blamed on all of us. But if one person does something wrong on the Thai side, that individual gets blamed.”

Suggesting changes to teaching methods or the curriculum meet with much resistance. “We understand that our system is completely different from the Thai system, but they don’t want to listen to ideas from us,” she said. “We keep hearing: ‘We are Thai. This is the Thai way’. That’s what we’ve heard many, many times. “Our students are not Western, so we can’t teach them that way.”

Faced with these ongoing frustrations, teachers find it difficult to stay, even if working with the students remains a passion.

“It’s all about the teaching, and how to get kids to understand and to learn,” said one teacher. “But what’s killing us is everything around us, the management, and the education system.”

Thus foreign teachers, especially in the Thai system, are in a perpetual juggling act: they have to worry about their students’ demands while also attempting to navigate a mysterious system that provides little to no explanation of its intricacies and idiosyncrasies. It’s also one that never quite seems to open its doors for integration, instead only inspiring unease, the kind that many farang feel from the start – it’s a feeling of not quite fitting, of being different, that catches, and once realised, never quite goes away.

Education, for better or worse

We’ve heard, in various forms, of the importance of education. It’s a predictor of success, a way to cultivate one’s minds, a mechanism for social change. Yet a failed education can have just as negative an effect.

Paolo Freire, a Brazilian philosopher and one of the most outspoken proponents of critical pedagogy, often criticised what he called the “banking concept of education”. In this kind of learning, students are viewed as empty accounts to be filled by the teacher – something that doesn’t sound too different from Thailand’s rote-learning system. Because teachers automatically assume their students to be ignorant, students are denied the process of inquiry that is foundational to knowledge. They become passive, forced to accept and adapt to the worldviews imposed upon them.

For Freire, the banking concept of education is more than just problematic: it’s oppressive. “Knowledge,” he writes, “emerges only through invention and re-invention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.” Without this inquiry, education is no longer a practice of free thought, but domination.

The problems of English proficiency in Thailand can’t be separated from issues of cultural integration. If Thailand really wants to improve its English proficiency, then we will have to accept the people that teach it and the different cultures they bring with them. Yet it’s also an issue that relates to the wider context of Thailand’s education system and those who control it. Without the desire to accept new ideas and the ability to ask questions, then we’re bound to be left behind, lost in a culture of repression.

Note: Many teachers interviewed for this article chose to remain anonymous. Jack C. Neale would like to state that his views are entirely his own, and not those of Prince Royal’s College.