A beautiful young girl sits before me – her fingers twirling through her hair, her hazel eyes glittering as she reveals the secrets of her past. “I had a monster in my head,” she says. “Eating disorders are mental illnesses, and I was sick.” The American teenager, who used to drastically restrict her food intake and over-exercise to the point of total exhaustion, is now finishing her schooling at Chiang Mai International School, before relocating to the United States to begin a college career in psychology and music therapy. “Since I ‘came out’ as having an eating disorder, so many girls have opened up to me about their issues. It’s become so normal, talking about it, and helping others.” Her name is Sydney, and her life and future are much brighter now.

“Before I start singing my song, I have…just a little bit of something I want to talk to you about…” A nervous Sydney stands on stage at her school’s talent show a few months before our interview (now on YouTube).

“This week is Eating Disorder Awareness Week,” she continues, gaining confidence. “And for those of you that don’t know, I suffered from an eating disorder, and right now I’m in recovery.” The audience buzzes softly with interest as she becomes more enthusiastic and explains the basics of what eating disorders are (mental illnesses) and what they are not (a choice, a diet or a way of life). She describes weight control behaviours – fasting, curbing food intake, vomiting and taking laxatives – and unveils disheartening statistics. “One in 10 men or women suffering with eating disorders will never, ever receive treatment. I want to help end all the stigmas and secrets regarding eating disorders, so that number doesn’t have to stay so low.” She finishes her candid speech amidst a roar of applause while deftly adjusting her guitar to begin strumming. In the first few moments of her song, titled “Monster” and written only the night before, she spills the following words, “All you need is someone to help you get out of your head. Your mind’s been consumed by whispers of ‘I’m not good enough.”

Sydney says she developed anorexia nervosa through her desire to be “happier,” which she equated with being prettier and skinnier, which in turn would make more people like her. “That’s how deluded I was,” she says, sounding surprised. “I wanted to be a beautiful woman in a magazine, instead of just wanting to be my beautiful self.” And that’s not an unusual thinking pattern for people suffering from eating disorders. “I was in a treatment centre in Colorado for two months,” Sydney continues. “We would have classes all about body image and our ideas, and one time we had to pick who we would want to be out of a random magazine. Most of us chose Photoshopped, unrealistic models, instead of people who were clever or kind, or who had achieved great things in life.”

One of the things Sydney says is so pervasive about eating disorders is the secrecy surrounding them, especially in Thailand. More often than not, the issues remain huddled in the shadows of Thai society, as opposed to many Western countries, where the incidence of eating disorders (EDs) became dramatically obvious in the mid- to late 1960s, and spread like a virus through the fashion industy in the 1970s. By the 1980s, bulimia nervosa was considered common, and today, disordered eating affects at least one in every five women worldwide. But it’s not just endemic to a handful of foreign countries, where destructive eating behaviours are deemed distasteful by the media and public. Non-Western countries with typically lower rates of EDs are now seeing a rise in debilitating, clinically-disturbed eating behaviours and abnormal attitudes regarding body image and self-worth.

Sadly, the abundance of knowledge surrounding EDs overseas paints a sharp contrast with Thailand, where mental health issues like depression, psychosis and anxiety disorders affect millions of Thais who go untreated. In Thai society, there are various stigmas that still need debunking, which range from those against people with mental illnesses to sex workers and HIV/AIDS sufferers. Seeing as eating disorders are explicably linked to mental health issues, open and unbiased discussions about EDs are needed in a public forum. As Dr. Kittiwan Thiamkaew from Chiang Mai’s Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital notes, “In the US for example, everybody understands what eating disorders are about. But in Thailand people don’t even know there’s a problem at all, so that’s why we don’t have the facilities or specialists to deal with it.”

Dr. Kittiwan offers many reasons why harmful body attitudes and chasing an unhealthy ideal are on the rise in Thailand, saying that the affected patients she deals with are lacking in life skills and proper socialisation. “Thai youth are glued to their televisions and computer screens, and this is where they are learning from. Actresses are thin so that they can look good on film, beautiful models are airbrushed and everyone on social media is trying to show off. It is hard for young people to realise that this isn’t reality.”

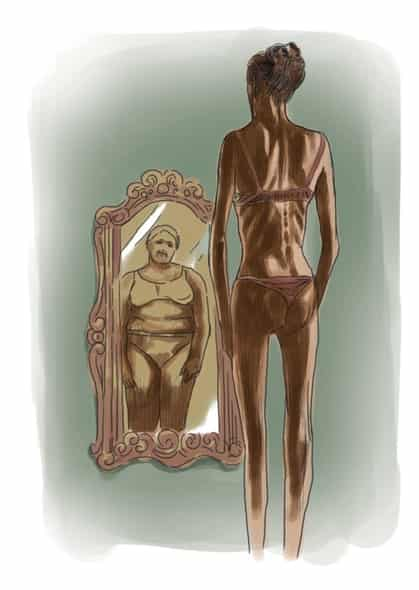

“Even though

they’re so thin we

have to force-feed

them, they still

see an ugly, obese

person in the

mirror.”

But what is reality, then? The often-quoted and often-offensive comment that Asian women are smaller and thinner than their Western counterparts? The persistent perception that being smaller and thinner means you are a better and more beautiful women? There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding the topic of women and eating disorders, one of which includes dieting – a very popular trend among young Thai women, and one of the biggest stepping stones to a full-blown eating disorder.

“As obesity has become more common, so have the advertisements promising women a skinny body,” Dr. Kittiwan says. “Thai girls love these diet coffees and teas – the ones all over Facebook – but there’s no proof any of them actually work. They’re all eating fast food, fried junk, and looking for a quick fix.”

While Thais are looking for a way to curb their calorie intake on home soil, persuasive articles touting Thai diets as a method to be thin have found their way into all corners of the globe. Forbes magazine lists 13 steps to achieve “Thai thinness” and the Examiner states that red meat is rare in the Thai diet, recommending that Thai meals should be eaten several times a week. But Thai meals are no longer just spice, rice and veggies, Dr. Kittiwan stresses. “Many Thais don’t eat the way older generations did, because of globalisation and the exposure to Western food. I grew up cooking Thai food and eating plenty of rice and vegetables, but that’s not the case nowadays.”

Some might agree the rise of eating disorders in Thailand goes hand in hand with the invasion of “Western food,” which is often mistaken as synonymous with KFC, McDonald’s and other fat-filled fry-up joints. But this is where Sydney’s perspective diverges from Dr. Kittiwan’s. “I definitely disagree with the notion that the West is exporting their mental illnesses,” Sydney says. “I don’t think eating disorders just moved to the East. I think they were here all along.”

There is evidence behind Sydney’s claim, such as a study led by the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry which compared groups of Thai and Australian university students in their respective countries, and found that the Thai group scored highest for unhealthy eating disorder psychopathology, as well as susceptibility to developing an eating disorder. The report concluded that these negative attitudes towards eating and food were already present in Thai society, and that pressures to be thin were actually more extreme in Thailand than in Australia. Another factor Sydney raises is the many cases of EDs that might go unnoticed – or even completely hidden – because women in Asia are expected to be naturally thin. Disordered eating is the leading cause of death among mental illness sufferers, making this expectation an extremely dangerous one.

“It’s scary to think of all the girls in Thailand who suffer alone, with no help from their families and friends, simply because there’s so little awareness,” says Sydney, who was lucky to be diagnosed in the early stages by her father. He had seen Sydney’s mother go through the same affliction in the past, and knew that genetics and exposure to destructive eating habits increase one’s chances of developing an eating disorder. He then took her to the treatment facility in Colorado, and encouraged her to continue therapy when she returned to Thailand.

Sydney struggled to find ED specialists here, but did manage to seek counselling for her anxiety and depression, which often go hand in hand with eating disorders. Dr. Kittiwan confirms this: “Eating disorders are linked to self-esteem, self-image, and self-worth, which are all mental issues that affect people significantly. Depression in ED patients is extremely common, and the most likely sufferers are young women.” She also notes the prevalence of EDs among transgender and transsexual communities, on which there is far less information available. The few statistics that are accessible point to substantial body dissatisfaction for gay and transgender men, compared to heterosexual men who might not face the same magnitude of pressure. Adds Dr. Kittiwan, “Let’s not forget that ‘ladyboys’ are also chasing the same ideal that women are chasing; they want to be small and thin too.”

Meanwhile, online communities of ED sufferers around the world frequently share images and advice which promote their unhealthy attitudes and habits, using the term “thinspo” (short for “thinspiration”) to motivate one another to be skinny. Googling “Thai thinspo” leads to countless blogs and forums plastered with Thai models and actresses, which goes against the idea that Thai women are succumbing to purely Western influences. Sydney says that growing up in Thailand played a part in her road to anorexia, and that mantras like “beauty comes from the inside” or “natural beauty is better” are definitely not encouraged here. “I hate the extreme ideals imposed on women here; they are so confusing and damaging to young girls,” she says. “Blonde, blue-eyed women are put on a pedestal, and more European-looking, half-Thai actors and models are revered in the entertainment industry. So all these Thai girls are just being told that they aren’t good enough the way they are – no wonder whitening creams, contact lenses, and cosmetic surgery are so popular!”

The National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA) lists a number of factors that contribute to the development of eating disorders, with psychological, interpersonal, biological and social factors all coming into play. Cultural pressures that glorify thinness and perfection and value physical appearance over inner qualities are all incredibly apparent in Thailand’s advertising media and show business. Online, the search terms “famous Thai celebrities” or “hottest Thai women” bring up scores of lists which heavily feature half-Thai actresses, models and singers, many of whom sport pale skin and European features quite unlike the common ethnic features of Thai people.

“So all these Thai girls

are just being told

they aren’t good enough

the way the are.”

Famous Thai-British model and actress Araya Hargate is plastered all over poster adverts while Thai-Danish Sririta “Rita” Jensen has bagged over 16 leading roles in soap operas – and according to Body Mass Indicator calculations, both women are severely underweight. “Young girls are constantly told what beauty is. They are not told that it differs from person to person, or that they should be beautiful on the inside,” Dr. Kittiwan says sadly. “Their thoughts are distorted at such a young age, and it takes a lot of psychotherapy to change that.”

Common methods of treating eating disorders are psychotherapy, nutritional counselling, monitoring, and, for some patients, medication like antidepressants or anti-anxiety pills. Extremely underweight patients might need to be hospitalised and fed intravenously to bring their weight back up to a functional level. Dr. Kittiwan says she herself has seen starving patients on the brink of death. “Patients with eating disorders are difficult ones, because it’s such a struggle for them to comply with the treatment. Even though they’re so thin we have to force-feed them, they still see an ugly, obese person in the mirror.”

Indeed, 20 percent of anorexia nervosa sufferers will die prematurely from complications related to their eating disorder, including heart problems and suicide, and young women with anorexia are 12 times more likely to die than other healthy women their age. “In Thailand it’s slowly getting better but I believe we have a long way to go,” says Dr. Kittiwan. “People need to be educated more about not only eating disorders, but mental issues as a whole. Then we can start to understand.”

Sydney feels the same way, noting that she didn’t realise her talent show speech and song would spur such a positive reaction from her peers. “I didn’t know it was going to be so personal. I just felt like I had to say something. We have to be informed and aware; that’s the only way we’ll end it all.”

She has since met numerous young girls who have struggled just like her, and heard inspiring stories of recovery, even from close friends that she never suspected had body issues. “I used to feel like everyone was constantly staring at me, picking my body apart, and I’m sure others feel that way too. You forget that it’s not okay to comment on other people’s bodies, like it is in Thai culture – it’s not okay to dissect people or make them feel like a spectacle,” she says.

Today, Sydney is veering far away from those negative pressures. She shares a recent time she felt happy with her body (a huge symbol of recovery); surprisingly, it was at the beach, back home in the US, where she describes feeling just like everyone else. “I was just me, in a bikini, and that was great! Nobody cared, and I wasn’t self-conscious. I was comfortable. I was happy.”

GET HELP

If you believe you are suffering from an eating disorder, or know a friend or family member who may be, please contact one of the following organisations or treatment centres.

Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital

053 908 500

Takes walk-in patients and those with eating disorders are welcome to seek out Dr. Kittiwan personally.

The Cabin (ED Counselling Services)

080 446 8850

The National Eating Disorder Association (NEDA)

www.nationaleatingdisorders.org

(+1) 800 931 2237