It was 1998 and Taveedej and Jeerapa Omaree were checking into a Chiang Mai hospital for a course of IVI fertility treatment. After trying for over eight years, the couple who are the successful owners of The Regent Chiang Mai, a cluster of gated communities totalling over 2,000 houses as well as a hotel, were desperate for a child. It was a long and stressful process, but the treatment was a success and the couple prepared for what would be the happiest day of their lives.

Due to their fertility complications, the doctors at their hospital advised against blood tests at four months to avoid any chance of upsetting the pregnancy. Confident in the doctors’ suggestion, they both agreed to forego the test and promptly forgot all about it. “What could go wrong,” Jeerapa thought at the time, “he looked so healthy on all the scans.”

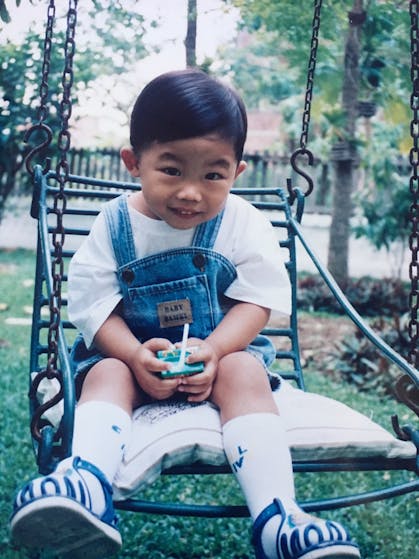

In 1999, baby Woody was born. All preliminary tests were normal and the proud parents went home to start their family. However, it was only a few days before complications arose. “He was my first born so I was not sure what was going on, but I’ve been around children enough to know there was something wrong,” said Jeerapa. “After seven days, Woody was still jaundiced, and he seemed constantly uncomfortable. I was worried.”

They took Woody to the hospital to run some blood tests and the result was devastating. They were told that Woody’s blood group was A, but his mother’s was O and his fathers, AB. As a result, his body has been fighting the remaining blood of his mother in his system. “At just seven days old, Woody had to have all his blood removed and replaced with fresh blood to clear his veins of any conflicting blood cells,” Jeerapa explained. “They injected into his head and drained the blood out of his foot.”

The next year was rough. “He was always sick, throwing up even after a few mouthfuls,” she said. “It was hard to make sure he had eaten enough food, and every time he was ill we had to rush him to the hospital. Even a small cold would take over his body, he was a sickly boy.”

Finally, over a year later, the doctors suggested they took a deeper look at Woody’s blood, agreeing with the parents that it wasn’t normal to be this ill, even for babies with a weak immune system. “Your son has traits of thalassemia,” the doctor told the parents when the results came back. “We need to test both of you, as one of you may be a carrier.”

Thalassemia is an inherited blood disorder in which the body makes an abnormal form of haemoglobin. Both Taveedej and Jeerapa turned out to be carriers, resulting in Woody being born with Beta-Thalassemia Major, the most severe form of the disease. Symptoms include the destruction of the red blood cells leading to anaemia, frequent infections, jaundice, enlarged organs, a failure to thrive and eventually death.

The doctor told Taveedej and Jeerapa the bad news. “Woody will never be a man, I doubt he’ll even make it to 15.” That moment despair turned to rage, Jeerapa explained. “I was furious at the doctor for saying that. Our son must be a man. We must save him. We both agreed that we would do whatever we could to save him.”

A Life for a Life

The doctors told the couple that the only solution was a bone marrow transplant, and a risky one at that since Woody was still so young. They also warned that the chances of finding a match were slim due to lack of donors. The process would replae destroyed or damaged bone marrow with healthy bone marrow stem cells. Bone marrow produces blood cells, so new bone marrow would produce new blood cells, void of any Thalassemia traits.

Both Taveedej and Jeerapa were incompatible, and unrelated donors are almost impossible to find. The doctors suggested that their best bet was to have another child. The risk was that the child would have a chance of also having thalassemia and the chances of compatibility would be unknown until after birth.

“It was an incredibly hard decision to make, but we felt like we had no other option,” said Jeerapa. “The doctors fertilised 12 eggs and inseminated them all at the same time. Five of the 12 eggs settled and finally only three remained.” After two months, the doctors had to decide on two, aborting the ‘weakest looking’ foetus.

“That was so harrowing,” said Jeerapa. “I had to see a psychologist who helped me understand that all of this was for Woody.” It took four months before they could test the two remaining foetuses, to see if either of them had thalassemia. If they did, all hope would be gone.

When the results came back a month later, the pair were again given bad news. “The doctor told me that one of my babies had thalassemia, but the other didn’t,” said Jeerapa, holding back a tear. “I told him I didn’t care and that I couldn’t give either one up, but he explained that should both foetuses carry to term, the chances of the other one becoming positive was high. He said that we had to perform selective reduction, effectively aborting one child.” It was also too late to remove the foetus, so she would have to carry them both until term.

“I cried so hard when the doctor injected the heart of one of my babies, and we saw it stop beating on the monitor,” Jeerapa said, her voice breaking again. “Every time I visited the doctor for checks, I could see its lifeless body next to Vanda, my daughter. It almost destroyed me.”

In the meantime, at almost two years old, Woody’s organs were swelling up, working overtime to combat the disease, and he was getting weaker and weaker.

“The birth was horrific. Our doctor was unavailable and a student doctor who did not know our story exclaimed in horror, ‘What is this? This isn’t a baby!’ when our stillborn appeared. Thankfully Vanda was born healthy and well.” Her blood was drawn and tested, and a few days later the parents were dealt with another blow.

Vanda was not compatible.

All hope was gone, and Taveedej and Jeerapa were not only saddened by the thought of Woody’s fate, but guilt began to settle in about Vanda. “Would she grow up thinking that she was only here to save her brother? Worse, being unable to. How could we ever explain that?”

A Glimmer of Hope

The only thing left was to find a compatible bone marrow donor. Only the family’s wealth made this option even remotely possible. A Thai doctor with experience working with stem cell banks had recently returned from the US and was working at Ramathibodi Hospital in Bangkok. The couple flew down to see him. “There were only five banks in the world at that time, and it was a relatively new technology,” said Jeerapa. “In fact Woody was the first ever Thai child to use bone marrow donated through a stem cell bank.”

Being Asian, Woody would need an Asian donor, and after contacting banks all over the world, they were directed to the Tzu Chi Foundation, a compassionate relief international humanitarian and non-governmental organisation founded in Hualien, Taiwan.

After sending Woody’s details to the foundation, they helped find a donor. To everybody’s surprise, a few months later a match was found, but their hopes were soon dashed as they learned that the donor had recently died in a typhoon.

Devastated, but determined, Taveedej and Jeerapa tried again and one year later the Tzu Chi Foundation had found a living donor willing to help. To put this into perspective, the Thai Red Cross Society says that finding a non-relation match is a one in 10,000 to 20,000 chance. In the early 2000s when Woody was searching for a match, however, the odds were at one in 50,000. To find two in one year is nothing short of a miracle.

“We were so happy,” Jeerapa said, now smiling. “We were told that she was a 27 year old Taiwanese female, though we were not allowed contact. It didn’t matter, our Woody had a chance.”

Last Hurdle

At three years old, the road ahead was going to be rough He would have to undergo a series of tests, operations and be exposed to intensive chemotherapy to kill every single blood cell in his body.

“Just before he went under aesthetic one time, he turned to me and asked if he was going to die,” Jeerapa said tearing up yet again. “It was so hard, I didn’t have time to reply before he was already asleep. Knowing that my three year old had thoughts like that destroyed me inside, but I had to be strong.”

Over the next month, Woody was sectioned to a sterilised ICU room in preparation for his chemotherapy. Jeerapa could only look at him through a glass pane, rarely being allowed in to touch him. By the end of the treatment, Woody was lifeless; his skin was black, his hair all gone. The chemotherapy had killed every single last blood cell in his body. All his plasma, white blood cells, and all his antibodies had to read zero on the charts. They had to be gone so that the new cells would not be rejected. Woody lay in bed in a catatonic state while he waited for his new bone marrow.

Woody had a small window for the transplant, as his chances of survival were getting slimmer by the second. The bone marrow itself also had a finite window of viability. So as his son lay in an ICU, Taveedej boarded a plane to Taiwan for the most important trip of his life.

“I was met at the hospital in Hualien by the foundation’s representatives who handed me the bone marrow,” said Taveedej. “The 1,000cc of marrow was contained in a plastic cool box which had to be constantly agitated to prevent it from dying. I had to keep it moving at all times from the moment it was placed in my hands to the moment I would hand it over to the doctors in Thailand.”

Then, disaster struck. Another typhoon was about to hit Hualien and all domestic flights back to Taipei were cancelled. Two nurses rushed him to the railway station only to find the platform heaving with people and no available seats left for days to come. What happened next amazed them all.

One of the nurses disappeared to explain the situation to the train conductor who made an announcement. “We have a man carrying bone marrow to save his son in Thailand, if anyone can give up your seat for this man, please stand up,” said the voice from the speakers. Taveedej looked around as the entire train stood up. Overwhelmed, Taveedej boarded the train only to soon learn that they would not make the flight home. Regardless, Taveedej sat there for three hours, constantly shaking his cool box of marrow.

In a last ditch effort, they called the airline and asked if there was anything to be done. When they arrived at the airport, they were amazed to see a team of ground staff waiting for them, rushing them straight through security and immigration. The flight had waited.

Within hours of arrival, the bone marrow was harvested for its stem cells which were injected into Woody’s heart. It was now a waiting game. Nothing more could be done. If Woody’s body rejected the stem cells, then he would die. If his body accepted them, it was still uncertain how and if he would recover.

Woody’s cell counts began to rise. 3, 5, 10, 15, 20…his red blood cell count rocketed, and brand new white blood cells were starting to appear. The transplant was a success and he was soon discharged from hospital with a new lease on life.

Not long after he was discharged, his red blood cell count started to drop, his body rejecting the new foreign cells. He was rushed to hospital in agony, his veins were tightening up and not enough blood was flowing through them. If the cells continued to fight, then Woody’s fight was over.

Breakthrough from Switzerland

“I sang to my son every single day,” said Jeerapa. “We had almost lost hope but we had be strong for Woody.”

Suddenly, a breakthrough new drug from Switzerland was found to help stop the body rejecting new stem cells after a bone marrow transplant. It was very expensive and never before used on a child. The risks were high, but with nowhere else to turn they had to try it.

It took three injections before Woody’s body began to produce more red blood cells. Soon the few remaining old cells began to succumb to the new stem cells. Over the next few months Woody had more and more injections. By the time he turned four, he was finally given the all clear. For the next ten years he would have to inject steroids to help prevent a relapse, but apart from that, he was just a normal, healthy boy.

“We saw almost instant improvement to Woody,” said Jeerapa. “He was healthier, he could stomach food again, his organs returned to their normal size and he was just a normal little boy!”

Interestingly, now with the stem cells of a female donor, his blood group has changed to O (the same as the donor) and he also has the biological signature of a female, despite developing into a fully functioning young male.

Now aged 18, he has shot past the 15 year lifespan given to him at birth, and is a talented pianist, can speak Chinese and English almost fluently and has recently been offered scholarships to a number of top American universities.

A Happy Ending

“We really owe a lot to the Tzu Chi Foundation,” explained Jeerapa. “When Woody turned 17, he really wanted to meet his donor so we contacted the foundation to ask if that could be arranged.” To their surprise, they are granted their request and soon the entire family flew to Taiwan.

As soon as they landed, cameras and news reporters surrounded them. Without realising it, their story had gone viral in Taiwan and Woody was hailed by the press as the adopted child of Taiwan.

Founded by a Buddhist Nun Master Cheng Yen in 1966, the Tzu Chi Foundation, which began as a humanitarian charity that ‘instructed the rich and saved the poor’, has expanded worldwide. It now provides support assistance in the medicine, cultural and educational fields and has recently opened a medical school in Fang, Chiang Mai.

“It was an amazing experience,” Jeerapa said of that visit to Taiwan. “Cheng Yen greeted Woody like a long lost grandson, and then took us to meet the donor. It was an incredible moment.” Woody prostrated himself at her feet with a wai and everyone in the room shared a tear before Woody performed two Chinese song to say thank you to both Wu Bao Jin, the donor, and the foundation.

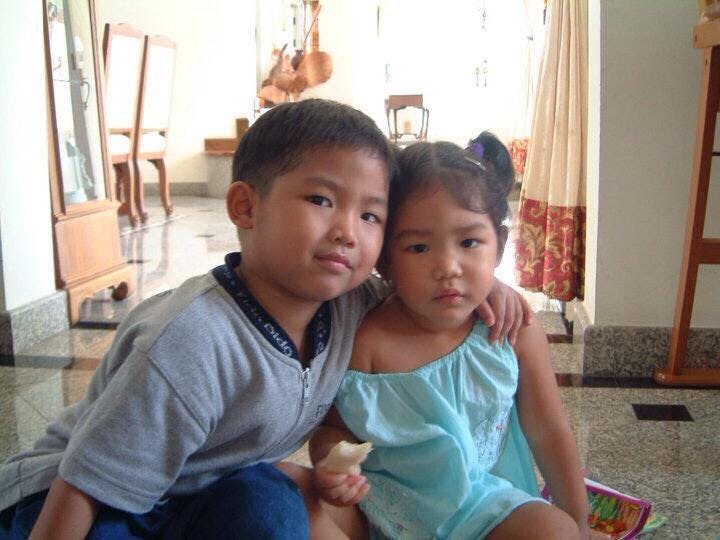

Since then, both Woody and Vanda have led normal, healthy lives together as loving siblings. “Although it was hard having to explain to Vanda the story behind her birth at first, she accepts it and knows that we love both her and Woody unconditionally.” Woody recently turned 18 and has accepted a scholarship to study business economics at Irvine University in California.

Over the years the entire family has been active in raising money to help families in similar positions. “Our greatest achievement was when we organised a charity concert in partnership with Sahapat PLC (a leading Thai distributor of consumer goods) where Woody played the piano. That single event raised 60 million baht, which we donated to the Ramathibodi Hospital to be used exclusively for poorer families who need treatment for blood and stem cell related disease such as thalassemia and leukaemia.”

The family also published a book, “Miracle…Power of Love” telling their story and giving information about thalassemia, with all proceeds being donated to the cause.

Writing this story has impacted me greatly, and I feel privileged that I have been able to hear about this incredible journey from Woody’s family first hand. I have decided that this year I will register as a stem cell donor with the Thai Red Cross Society in Bangkok via the National Blood Centre (022 564 303). Around 26 million people have registered as donors around the world, 97% of which are Caucasians and Thailand is in urgent need of stem cell donors, especially those of mixed-race. Although their budget is limited, I urge you all to register as donors if you can. It is painless and quick, just like a blood donation, but it could save a life. A life just like Woody’s.