Citylife published an article in 2017, ‘One sleep closer to home: housing for Chiang Mai’s homeless’, where we wrote about an upcoming 30-million-baht homeless shelter for Chiang Mai’s then-150 homeless people, which was to be completed by 2018. Four years later and in the midst of a global pandemic, we thought it was time we revisited the homeless to see how they are faring and whether the dream home that was to shelter our city’s most vulnerable had become a reality.

(Spoiler: it has.)

But before we get to the success story that is Term Fun Home, we sought out the director of the Chiang Mai Protection Centre for the Destitute, under the Department of Social Development and Welfare and ended up spending a morning with him and his team of three social workers

“We deal with immediate needs of the destitute who are between the ages of 18 and 59,” said Sukit Rakchart, director of the centre. “We have a network of 15 other governments agencies, meeting once per month at least, working together to help those who are the most vulnerable in society. We are also in contact via social media daily about specific cases. While each agency has a different focus group – highland people, the elderly, the youth, orphans, abused women, the addicted, disabled, etc. – we share resources, expertise, and support. Working together like this allows us to be more responsive and efficient, ensuring that no one falls through the net.”

In our 2017 article we interviewed Nantachat Nusrikaew of the Human Settlement Foundation, who was tasked with spearheading the upcoming Term Fun Home. We recall his frustrations at the time at the lack of a comprehensive safety net for Chiang Mai’s destitute, saying that some government agencies were not as responsive as they could be.

Fast forward to today and Nantachat and a handful of volunteers oversee Baan Term Fun, where 50 units are today filled at just overcapacity (units can be one bed in a dorm, a shared room or a family room). Wichian Tala who volunteers at the shelter, told Citylife, “This pandemic has really helped streamline the various agencies and organisations which are tasked with helping the destitute. With such a focus by the public on the current dire economic situation, many government agencies have really stepped up and are working together in a way which we had never seen before. We, along with many other foundations and NGOs are finding it much easier and more efficient to work with government bodies, as they are realising the important role they can play in changing someone’s life, and it is making a real difference.”

While it has long been known – and scorned upon – that Thailand’s elderly receive a mere 600 baht per month when they turn 60 (with one hundred baht increments added per decade…until they reach 90 years old at which time they receive 1,000 baht per month), and our handicapped receive 800 baht per month, we learned that there are many other avenues to access support which are now becoming more accessible to those who need it the most.

“There is a small fund for sex workers with HIV,” explained director Sukit, “as well as up to 9,000 baht per household per year for the very poor. The government even has a 5,000 baht per year career capital for those wishing to make a fresh start. Our centre spends around six million baht per year on 2,000 cases. If they don’t know how to find us, we reach out to them. Then there are all the other agencies with their own funding and resources.”

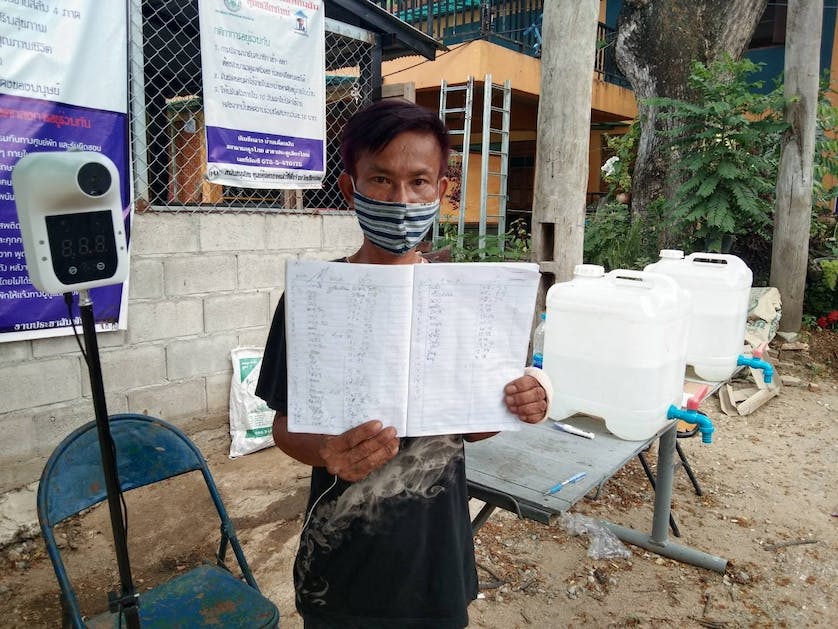

“No one needs to starve or live off the street in Thailand,” said Isaree Chakphancheevee, one of three social workers at the centre. “Nearly everyone you see homeless in Chiang Mai city today has access to the four basics in life – food, shelter, clothing and medicine – but for various reasons, they choose not to opt in. In order to receive government help, they must comply with the government system. Some just don’t want to. We get between 200-300 new cases per month now, whereas pre-pandemic we had around 100. So each day we go out and investigate; whether it is a newly released prisoner with nowhere to go, a homeless person from another province found wandering the streets, a family whose home has burnt down, a mentally ill person attempting suicide…whatever the crisis, we are there to help alleviate their suffering in the short term. The major crisis was during the first lockdown last year when many day labourers lost their jobs and homes. This led to many becoming homeless overnight. But we managed to either send them home to their communities where there are local support systems, house them in shelters or help train and find them jobs. This year people are more prepared and are coping – just.”

Of the 114 registered homeless people in Chiang Mai today (94 men, 20 women), the majority are day labourers who are either alcoholics or suffer from mental illnesses. Each and every one is registered with the centre and are visited regularly.

“There are three main ‘families’ of homeless,” added another social worker, Orapan Jitjun. “They live around Tha Pae Gate, Chang Phuak Bus Station and the Flower Market area by the river. These day labourers support one another like family. If one works today, the next day, they may go get drunk while another works. The numbers have not increased over the years because as new cases come up, we manage to find ways to help them. Most of these people have been known to us for 10-15 years. The remaining are housed at Term Fun Home, where there is zero tolerance for alcohol or drugs. Another 15-20 are scattered across the city.”

The centre shares a large piece of land with the Highland People Development Centre and on-premises there are two houses, one for each sex, each with five beds.

There are currently three men being housed in the traditional wooden buildings surrounded by a well-tended garden. One lies injured on a bed following a drunken episode, where he will remain for the fortnight the centre allows for the homeless to stay.

“During that time we investigate,” said director Sukit. “If someone has family, we find them. If they have a local community, we contact its leaders and arrange for their return and care. Communities across Chiang Mai, and Thailand, have funds to help their own. If the funds are low, we either subsidise or help them access more. One really vulnerable group of people are those without ID cards. We help them to get ID cards, which is essential to access all welfare.”

“As homeless people have no fixed address,” said Nantachat in 2017. “They already lose a lot of rights that are taken for granted by you and me. If you have not made any contact with any government department for over 20 years, you are registered as dead…but so far the authorities have been very reluctant to help.”

Times have changed, said Orapan who says that she and her fellow social workers often take the risk of being a guarantor for those without any ID, taking them through the entire process, despite legal advice warning them against such a stand.

“The day they receive their ID we register them at Term Fun Home. Once they have an address, they can get back on their feet,” she explained.

Wichian agrees that the centre has come a long way. “Covid forced everyone to work closely together and by having all relevant agencies discussing cases together and with public scrutiny, they began to become efficient and effective.”

Term Fun Home is a progressive shelter run as a foundation with government subsidies and donated funds focused on helping the homeless to get back on their feet. Rules and regulations are set by the ‘members’. Most of the management, even the banking, is run by members themselves with only a couple of volunteers helping out as facilitators, or, ‘nannies’. Members sleep in the dorms for free for the first ten days, after which they pay ten baht per night. They also contribute two baht per day towards a shared benefits fund and there are jobs available such as recycling (though with lack of tourists the 18 professional recyclers have been reduced to two), with money being banked daily. According to Nantachat, many homeless spend what they earn each day in fear of being robbed at night. This may be the first time in their lives they are able to have savings. As members gain their footing, they can choose to rent rooms on a more permanent basis – up to 400 baht per month – or eventually save enough to buy their own subsidised homes (though no one has yet reached that lofty goal). The home’s concept is to have members immediately paying bills and earning a living, if only symbolically. The more earned, the better the bed, which in turn helps them head towards full independence.

“Then there are the homeless who will never get back on their feet,” explained director Sukit. “These are addicts, the infirm or very elderly. For these people, we have a 250 bed home in San Mahaphon Reception Home for the Destitute in Mae Taeng. Here, they go when there is nothing left. Beds open up when people pass away. If it is overcrowded then we work with NGOs which offer shelters. This is long term and for those most desperate.”

“Most of the funding for welfare comes from the sin tax,” explained Wichian. He went on to praise the centre as well as other government offices for having changed their attitudes for the better over the past year. “Their data is trustworthy; we check. The public sector has been pushing for transparency and action and the results are that people are being helped.”

Wichian explained how Chiang Mai’s poorest are managing to survive without being homeless. “The government’s 600 baht per month may not sound like a lot, but a family can pool this money to buy only the absolute essentials such as rice, chicken bones or fish sauce. Each day they just have to spend five or ten baht on some vegetables or go pick some from the side of the road. Money can be subsided with low paying jobs such as making funeral wood flowers or the occasional day labour. As social security covers health and education, there is less pressure. This allows people to survive the pandemic. We are currently feeding around 60-70 homeless people per day, but the long lines you’ve seen for food and supplies around town over the past year are not comprised of the homeless, but what we call the most at-risk. These are the people I just mentioned. They have homes, they have basics, but the donated food is also very important and necessary.”

“Between the various departments and NGOs, we are confident that all Thai people have access to welfare from birth to death,” said director Sukit. “Our job is to focus on adult homeless and destitute, including beggars and those who live in public spaces. To that end, we are keeping on top of the situation and able to respond to all current needs.”

“You can call 1300 to report any emergencies,” added Orapan. “The people who call us are concerned citizens. They call because they want to help, not because they are disgusted or fearful. While we have a budget to help people, we always welcome donations, especially at this time. So please feel free to drop in with any donations to the centre.”

Wichian also added that Term Fun Home is open to all donations and he can be reached in English and Thai at 0997133787 and here.

Read Aydan Stuart’s 2017 article ‘One sleep closer to home’ here.