Chiang Mai’s love affair with coffee may be new, but it is strong, passionate and promising to endure. Our mountains produce high grade coffee which rivals some of the best in the world and our plethora of coffee shops are gathering places where beans, conversations and ideas are brewed. There are many cities across the globe — Seattle, Melbourne, Vienna — where coffee is deeply embedded into the city’s DNA and there are many countries around the world — Brazil, Ethiopia, Jamaica — which are renowned for the production of excellent coffee. Yet Chiang Mai joins a small group of cities — Adis Ababa, Sao Paolo, Bogota — which enjoy both a vibrant coffee culture as well as being within a stone’s throw of the cool mountains on which it is all grown.

Our coffee story is also unique. “In each cup there is a story. It is a story of drug addiction, of poverty, of deforestation, of a King who worked hard and came up with a vision to help his people and of challenges almost unimaginable. It is also a story of faith, of passion, of prosperity, of education, of overcoming disadvantages, of international cooperation, and of hope,”

I wrote in the book ‘Drink Coffee’, the Citylife-produced book commissioned by Chiang Mai Coffee City and Lanna Thai Coffee in 2018.

Over the course of two years we interviewed nearly 70 people who have been integral to the blossoming of our coffee industry, from His Serene Highness Prince Bhisadej Rajani, President of the Royal Project, to Karen village elders who kept cultivating coffee at HM King Rama IX’s request, even when there was no market for their beans. Then there were the early forestry officials who risked their lives in opium-ridden mountains to encourage the growth of coffee, researchers and agronomists who worked to develop the quality of our beans, to today’s trendy and successful entrepreneurs and baristas who are creating ever-growing markets to support our coffee farmers as well as the farmers themselves who, together, are elevating the quality of life for thousands of hill people. This story draws from the mountain of research and interviews generated for the book.

A Glance at the Past

While there is supposition that coffee was brought to the court of Ayutthaya by Dutch merchants on their way to Java in the early 18th century, the first official records of coffee in Siam was when King Rama III (1788-1851) had coffee planted in his palace gardens. By the time of King Rama V’s reign in the late 19th century, Thailand had become active in the global trade and many royals and nobles, educated abroad, had become coffee drinkers.

In 1904 Dhimun, a Muslim man from Songkhla Province, brought Robusta coffee from Sumatra, which was the start of the south’s Robusta industry which supplied not only Thailand’s instant coffee demands for the next century but which was also exported to the likes of Nestle. Coffee wouldn’t be cultivated in northern Thailand for well over half a century.

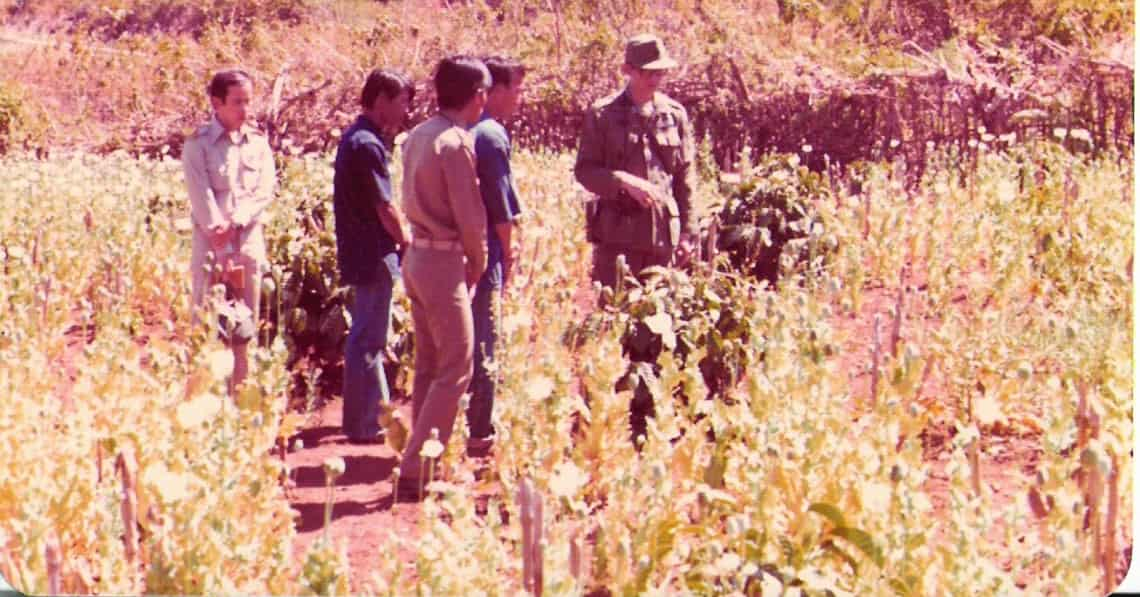

Alarmingly, in 1962, a joint Thai-United Nations survey revealed that on average each household in rural Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai cultivated between 3-4 rai of opium. By 1979, it was estimated that Thailand grew over 10 million rai of opium. The north of Thailand, part of the infamous Golden Triangle, was in trouble. Seas of bright red poppy flowers blanketed remote mountain tops where no government officials dared to go. It was poverty, the destruction of the environment and addiction which lead to the widespread growth of the notorious drug, and paradoxically, which resulted from it.

In 1969 a Thai king visited a hill tribe village for the first time. King Rama IX was so moved by the poverty he saw that he put up 200,000 baht of his own money to set up a highland agricultural research station, appointing his friend HSH Prince Bhisadej Rajani to take charge, an initiative which would eventually morph into the success story that is the Royal Project today.

“There were opium fields everywhere,” said Richard Mann who first came to Thailand in 1950 to spread the word of God, but who eventually changed careers and became Director of a United Nations project for highland replacement crops. “There was no government presence at all in the mountains; no offices, no projects, no officials. No one knew what to do about the opium and no one seemed to care.” Even though Thailand had made opium illegal in 1958, there was no government policy in place to deal with the problem.

“I must admit that I didn’t know anything about drugs, I had never seen opium or heroin,” said Police General Chavalit Yodmani of his arrival to the north in 1971 as Secretary of the Office of the Narcotics Control Board. “It was a steep learning curve. I remember at one point the United States wanted us to release Agent Orange throughout the region to kill opium plantations, but we refused. So we trekked into the jungle, lived and ate with the hill tribes, grew new plants and showed them how it can be done.”

Recognising that Thailand’s drug problems could impact the world, in 1971, the UN pledged two million dollars to support Thailand’s efforts to eradicate drugs.

The following year, Prince Bhisadej was enjoying a beer at the Rincome Hotel lobby, mulling over what to do about the opium conundrum, when an American man joined him for a drink and conversation. “He suggested I introduce Arabica coffee to our mountains. He told me that even cannibals in Papua New Guinea were growing it successfully. So I went to get permission from His Majesty, then contacted the Australian government, as Papua New Guinea was their territory then, and we were given some seedlings to plant. I would take a bottle of whiskey up to the village once a month to check on the coffee plants…and so it began.”

By 1974 different strains of coffee were being grown on multiple hill stations across the north. With financial help and expert support from around the world, it was soon discovered that our mountains were optimal for the growth of Arabica (interestingly, the best locations for coffee to grow were where opium used to). Like everywhere else in the world, plant rust was an early threat to highland coffee, but through focused research and development, the plants slowly became inoculated from this insidious disease. In fact, Thailand’s Arabica journey has yielded such success it is now recognised for not only being one of the most resistant against plant rust, but also for producing great yields, averaging 215 kgs per rai each year.

Payo Tarro, a Karen village head from Baan Nong Chom, Chom Thong District misses his annual walks with HM the King. “He came to visit us in 1974 and that was when I showed him three coffee plants we had growing. We didn’t know what to do with them, but he told us to take care of them and that people all over the world were drinking coffee, telling me to plant more and that he would be back with help. The next year, and for many years after, he came back and we would walk across the hills to see the coffee plants. Eventually he built a Royal Project here.”

Payo’s first harvest yielded 10kgs which he gave to HM, who immediately gave it to researchers. “We didn’t know that coffee could be an economic crop. But he did; he issued an order for one million Arabica seedlings to be planted. Think about it, from the 10 kilos of coffee we gave to him, he eventually turned that into a million plants.”

Once the coffee was planted and harvested, it needed to be sold. Yet there was no market in Thailand for Arabica drinkers as Thais were still only drinking instant coffee.

Owner of Hillkoff Coffee, Theera Taksaudom, began his business in the ‘60s by buying goods from hill people and finding markets for them. So when the UN asked him to find buyers for the Arabica coffee grown in the highlands, he agreed and took some down to Bangkok to sell.

“No one in Bangkok would buy any,” he said of his first trip. “All they wanted was Robusta. So I sent some beans to Singapore to be tested and the results were that our coffee was excellent. I used that to find a small market, selling my first six tonnes to Nescafe. I returned and told the UN that we had a market.”

All was going well until the coffee crash of 1989, which saw prices drop worldwide, Farmers slashed their crops, and beans rotted in godowns. Nothing could be done to help farmers except for small government subsidies, and most people involved in the emerging coffee industry resigned themselves to failure. Sadly many farmers began to grow other crops, which, unlike coffee, didn’t require shade, leading to swathes of deforestation. By the time coffee prices began to rise in 1997 farmers found themselves unable to grow coffee for lack of shade.

That was a great lesson in spreading risks and many farmers today plant numerous crops to ensure this never happens again. It took a long time for coffee to recover, the few farmers who left their crops alone reaped the most rewards when the markets eventually reopened.

Thankfully, at the same time that the price of coffee began to rise, Thailand’s economy also had a great boost from the 1998 Amazing Thailand campaign, which saw an influx of tourists, many of whom appreciated a good brew. Thailand’s first coffee chain, Banrie Coffee, opened in 1997, expanding to 110 branches today, and Starbucks followed the following year. Arabica had got its foot in the door.

Savour the Present

“We are fortunate in that as our consumers grow, we have the resources to support the expansion and growth of our farmers,” said Naruemon Taksaudom, Cluster President of Chiang Mai Coffee City and MD of Hillkoff. “We have farmers who are becoming roasters and roasters who are opening coffee shops. A consumer can visit a coffee plantation, meet a farmer and take some coffee to trade, creating their own brand. There are many roles for many people to play. This is good news up and down the chain.”

Much of the success of the supply chain strategy has got to be placed at the door of the Lanna Thai Coffee Hub, a project under Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Agriculture, which was tasked with organising activities to develop the quality and standards of coffee as well as linking farmers, processors, business owners and consumers.

“Coffee people are kind, cooperative and well-intentioned,” said Professor Dr. Yaowaluk Chanbang, of the Lanna Coffee Hub. “Now that we have created a network we can see the big picture, and be far more effective. It is like we are all singing the same tune; we are no longer working at crossed purposes.” She goes on to say that upstream farmers now have a solid foundation of knowledge and expertise, as well as resources, at their disposal while passionate consumers are supporting the industry’s growth.

Today the four Northern provinces grow over 20,000 rai of coffee. “By working with roasters who are able to draw out the flavours and aromas, we began to weave a story for each mountain, creating brand identities for each of them. From there we began to blend, creating exciting new products, as brands are easy for consumers to relate to,” added Decho Chaitup, who runs the social enterprise Pracharat Rak Sammakkee.

A crucial result of the growing coffee industry is its impact on the environment. “When I tried to plant coffee in the open it died, so now we plant them under large trees,” said Supol Kengprasarnkhun a local farmer from Omkoi District. “We all know now that we can’t cut a single tree.”

With constant workshops, cupping events as well as rigorous testing of coffee grades, farmers are also becoming drinkers, making them appreciate the importance of quality.

Then there are the roasters. Once a farmer has produced a great coffee bean, it is handed over to roasters to work their magic, by bringing out the best characteristics. Chiang Mai’s top roaster is ‘Moddangfire’ also of Hillkoff’s Taksaudom family. “If the quality isn’t good to start with then I am not interested. This is also so that the farmers learn to develop their beans themselves, and not rely on roasters to fix their flaws. As our industry gains knowledge and expertise, we must also develop the palates of the consumers. It’s a delicate balance; you can’t be arrogant and tell people what to drink, this is why baristas are very important, as they must both educate and draw people in.”

If you are a coffee lover, then you surely must have visited Nimmanhaemin’s trendy Ristr8to, owned by World Latte Art Champion 2017 and Chiang Mai’s most famous barista, Arnon Thitiprasert. Arnon sells a staggering 1,000 cups of coffee each day and is highly involved in the competitive scene, believing that it raises awareness as well as attracts visitors. He is one of the many successful Chiang Mai coffee entrepreneurs who have shaped, grown and reaped benefits from the bourgeoning coffee culture of Chiang Mai.

Black Canyon is another similar success story. Its owner, Prawit Jitnarangpong opened his first branch here in Chiang Mai with the intention of supporting the Royal Project, selling iced coffee from his one espresso machine. Today, there are branches of Black Canyon across South East Asia. “I look around now at all the cafes in Chiang Mai and I feel so happy for their success…we a have created a legend.”

Brewing the Future

All this buzz isn’t just from the caffeine. It is obvious there is great potential for our Northern coffee industry.

“Coffee is a drink which has two distinct identities,” said Teerawat Wongworatat, Vice President of the Asian Coffee Society. “Its place of birth, so to speak, and how it is brewed. Our story of origin is no less interesting than others’.”

“As to consumers,” agreed Varee Sodprassert, President of the Thailand Coffee Association, “as Thai people have become financially stronger, our habits have changed. In the past, the 3 in 1 instant coffee sachets were popular, but as people have begun to be able to afford freshly brewed cups, and have also developed more sophisticated taste buds, their requirements have changed. If farmers wish to develop high grade coffee, there is now a market, and the farmers have the luxury of setting the price. At the end of the day it is about the flavours, so our focus is on the process and how to draw the most taste and best aromas out of the beans.”

It appears that Chiang Mai’s coffee culture, forged through the fire of time, experience, passion and hard work, is paying the gift forward to future generations. With sustainable development as the organising principle, focusing on economy, society and the environment, as well as the fact that Thailand is still importing vast quantities of coffee, our own yield is not enough to fuel our own demands, let alone have any left over for export. It is clear that there is massive potential for growth for our home-grown industry.

Next time you follow the enticing aromas into a café and order yourself a freshly brewed cup of Thai highland coffee, remember the words of King Rama IX, “It is a matter of humanity to want to help our mountain people to have a better quality of life. By being able to cultivate crops which had sustainable economic benefits, those in remote areas were able to not only sustain themselves, but develop and prosper. By doing this we also helped to solve the opioid crisis.”

And it’s all just so damn tasty.

For more information visit

www.lannathaicoffeehub.com.