“Nimmanhaemin Road will be the next place with a bicycle lane,” announced Poonsawat Vorawan, former Deputy Mayor of Public Works, Chiang Mai Municipality in Citylife’s August 2001 issue on city zoning.

Our cityscape has changed dramatically since the turn of the millennium, though not all according to plan, obviously. Seeing that we are still suffering from growing pains and remain in the midst of great, though haphazard, changes and expansions, we thought we would take a look as to how intentions and plans mentioned in the 2001 article have been realised…or discarded, and what is going on with the city plan today.

The biggest topic at the time of that early article was the proposed underpasses along the Superhighway and the proposal’s vociferous protesters, who did manage to halt all but the airport overpass in favour of more discreet looking underpasses. The second ring road was also being built at the time and the third was a proposal awaiting approval. The article mentioned a confusing lack of clarity in which different roads came under the responsibility of different departments, a problem that hasn’t changed. Chang Klan Road was, and still is, having a hard time tidying up its Night Bazaar street vendors, the tedious public transportation and songtaew conflicts are an ongoing saga, Mae Kha Canal is still the stinking cesspool various elected bodies have been claiming to try to clean up for years. Sixteen years later Chiang Mai has grown exponentially, yet has there been any development?

Visionary Founders

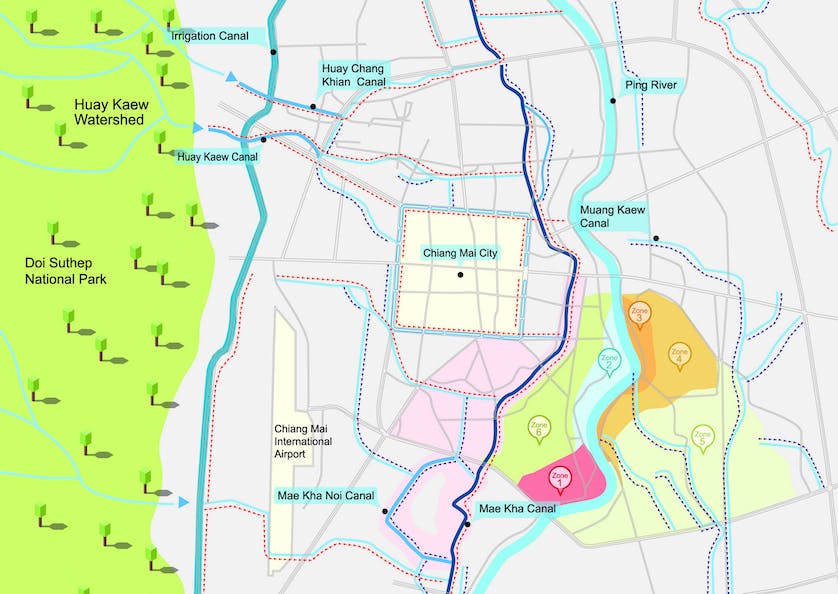

We shouldn’t be in the mess we are in. Seven hundred years ago our forefathers gave much forethought to city planning. As explored in our July 2017 story, Do We Have a Flood Problem? King Mengrai founded the city with great deliberation, placing the moated city to the east of the mountain with plenty of natural reservoirs acting as buffer between any potential runoffs from Doi Suthep-Pui (concreted and covered, the damaging floods of last May were exactly what Mengrai was trying to avoid). The city was also buffered from any potential overflowing of the Ping River with its network of natural canals, importantly the Mae Kha Canal which runs parallel to the Ping. Poor planning and sheer ignorance over the past half century have led to the blockage of these canals in favour of road systems.

Chiang Mai waterways

Following a few prosperous centuries, Chiang Mai suffered from a total exodus for a few decades following Burma’s attacks, domination and then neglect from the 16th to the 18th centuries. By the late 18th century, it was said that tigers were roaming the abandoned city streets. So when Phra Chao Kawila, with support from Siam’s King Taksin, built up his forces towards the turn of the 19th century, he marched far afield sweeping up people from the outreaches of Lanna Kingdom and as far as China and Burma, bringing them south to repopulate Chiang Mai. Again, there was great foresight and deliberation in his planning and soon the city was zoned in an organised and systematic way. The old moated city soon became home to monks and the high ranking; whether royalty or military. Tradespeople and those with skills were settled in peripheral communities outside the moat, but still safely ensconced within the outer walls — laquer craftsmen from Chiang Saen and Burma’s Kentung were located to the south side of the wall, the Shan were to populate the Wualai and Chang Moi area and many farming communities were sent further afield to San Sai, Sankampaeng and Sanpatong, lining the caravan routes in and out of the city. It all made sense.

Drawn & Quartered

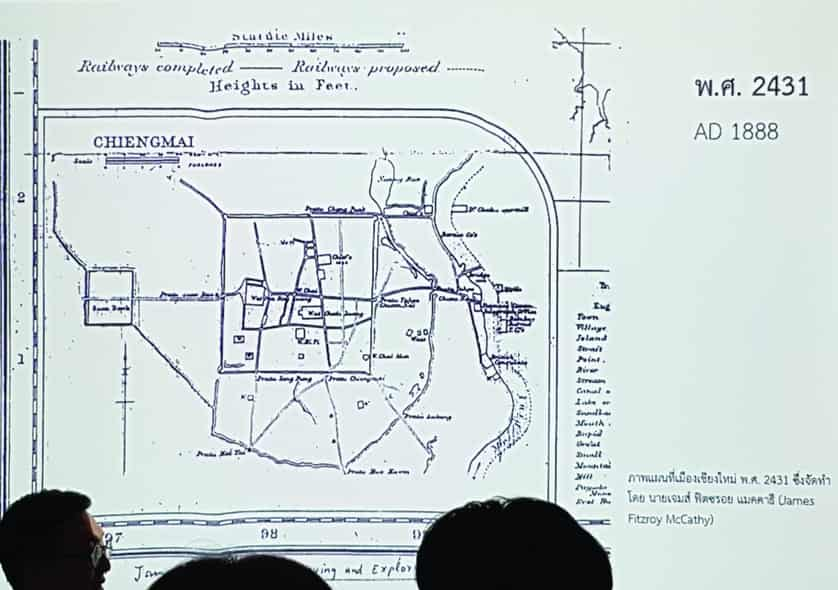

“The first map of Chiang Mai was drawn in 1888 by the royal order of King Rama V with the aim to estimate the area of Siam’s power in Chiang Mai,” explained Asst. Prof. Dr. Sant Suwatcharapinun of Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Architecture who has analysed the physical transformation of the city since the 19th century. “You can see that the royal Lanna family were still big property owners in the inner city area, while both banks of the Ping River were by then occupied by foreigners such as teak loggers and missionaries, including many Siamese, as they too were at that time foreign. The west bank soon became the homes of both the Siamese Commissioner and the British Consul while the east side welcomed the city’s first church as well as homes of teak wallahs, along with their many Chinese labourers. It is believed that Lanna’s rulers offered such locations to foreigners because it was further away from the city centre.”

The first map of Chiang Mai

By the time the railway arrived in 1921, the cityscape was once again transformed.

Tha Pae Road and the banks of the Ping River had become business hubs with Chinese migrants settling in and running markets such as Warorot and Lao Cho Alley, working side by side with, and collecting taxes for, their Lanna royal family landlords. Siam had established city hall behind today’s Three Kings Monument and the American Presbyterian missions had set up a number of schools and hospitals to the east of the Ping.

When King Rama V began the process of unifying Siam into what would soon become Thailand, Chiang Mai’s ingrained ideologies, often based in cosmology, morphed into rationalism. While progress was needed, much of the ancient wisdom was soon to be lost. The government began to establish hospitals, and later a university in what was then considered a scared forest where no one would have dared to touch before. Kruba Srivichai had already arguably degenerated Doi Suthep’s sacred status by building a road up it, unknowingly laying the foundations for Chiang Mai’s tourism industry to come, the airport soon followed the railway, though initially serving a military rather than a commercial purpose. Public works such as sanitation and electricity was being implemented citywide by the ‘60s and developments remained loosely in line with King Mengrai’s vision…until the natural reservoir which was the city’s buffer against floods was filled in and turned into The Superhighway in the ‘60s, and then completely covered over to build the Rattanakosin Road in the ‘80s.

Planning & Plotting

In 1984 the Ministry of Interior launched the first Chiang Mai City Planning, covering 100 sq km in Muang District, Mae Rim and San Sai. “The immediate effect was the population expansion outside the urban area, mainly along major highways, due to higher tax in the city,” explained Dr. Duangchan Aphawatcharut Charoenmuang, Social Research Institute, Chiang Mai University. “The problem was that these outlying residents still had to come into the city for work. So the first reform also pushed for controlled decentralisation from Chiang Mai municipality. Education and employment were dense in the city centre, while those in suburban areas had previously lacked economic growth, this was when the various districts began to administer their own budgets.”

Somwang Bunrayong at his office

“One City Planning Act is applied for five years, though it can be reformed twice afterwards, for one year each time, extending each City Plan’s lifespan to seven years,” said Somwang Bunrayong, Head of Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning, Chiang Mai Office. “Unfortunately after the plan expires, there are no supporting policies during the renewal of the plan, creating an empty gap where anyone can do anything they want without any regard to the City Planning Act. The gaps have caused housing estates to grow like spores, especially in the green areas between the second and third ring roads as the lands is cheaper. This uncontrolled expansion is not only disorganised, it also exploits public infrastructures such as water and power which have to stretch to reach these areas.”

“The expansion of low density areas also makes it harder to develop mass transit,” added Asst. Prof. Dr Nawit Ongsavangchai, Faculty of Architecture, Chiang Mai University. “The distance to collect the amount of passengers would be further compared to the same area with higher density. Meaning, the mass transit investors have to invest more.”

Power & Politics

Yet another frustrating and frankly outrageous example of overlapping and abusive authoritative power structures is that it is the Provincial Administrative Organisation’s (PAO) Department of Lands, with the (easy) approval of local authorities, which gives permission for the construction of housing estates. The City Planning Office has almost no say in the matter. Interestingly enough the Buranupakorn family, whose patriarch is the President of the PAO, is also the owner of some of the largest housing developments found in these green zones.

“In the first 1984 plan, high rise buildings were permissible in the yellow zone, or low density residential areas. The problem quickly became apparent when towering condos were built next to private homes. Another problem arose when investors started applying for multiple permits at a time to be used at a later date. Many such permits are still active which is why areas such as Soi Wat Umong is still seeing high rises being built, using decade-old permits, in spite of the law having changed to ban high rises in the area,” continued Dr. Duangchan. Apparently it is the norm for a flurry of construction permits to be sought just before each reform.

The flurry turned into a free-for-all when the 2006 City Plan expired, and due to an assortment of reasons academics blamed on politics, politicians on protesters and bureaucrats on administrative processes, It didn’t get renewed until 2013, leaving a whopping seven year gap when the city was rudderless when it came to planning.

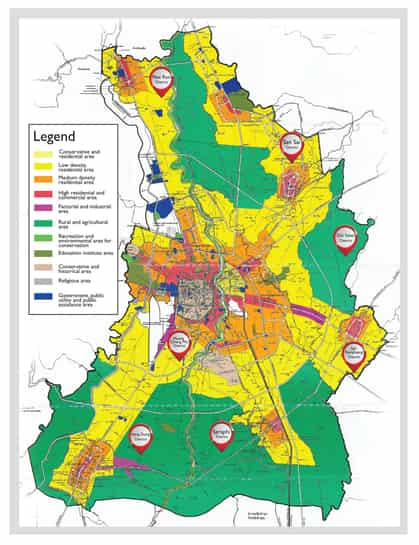

Current Chiang Mai City Plan

“As soon as I took office I activated the draft policy on city planning that was written after the 2006 policy expired but was never enforced,” explained Somwang. “However, it was already out dated and would expire soon after, so I also revoked the expiration loophole and replaced it with a plan evaluation every five years. This means that we never have a gap in the application of zoning laws again. Our next evaluation was due in 2018, but we started the process in 2015 and with the help of academic scholars, researchers, community leaders, lawyers and local administrative offices, we applied the new plan earlier this year.”

There is much pressure on Somwang, with local leaders lobbying for their areas to be red which marks the non-height restricted business zone where land prices rise correspondingly. Then there are the NGOs who are fighting for the green zone, which marks agricultural land where up to 50% of the area must be green space. With such conflicts of interests, Somwang says that he turns to academic expertise to help with the bigger picture.

“Currently, the City Plan covers two layers of development; zoning and transit. Now the next step for us is to create the urban resilience. This plan will expose the vulnerability of each area, assessing its exposure to disasters. I am going to be whammed at the panel discussions with the communities,” laughed Somwang, shaking his head. “Nobody wants to hear bad news.”

“We have not hit the critical point yet and that is why no one wants to hear it,” agreed Dr. Nawit who reminds us that Chiang Mai sits on fault lines, as witnessed by the remains of Wat Chedi Luang’s pagoda, hit by a giant earthquake in the 16th century. “Buildings are everywhere and we don’t know which ones will collapse. It is simple to fortify against this risk in construction, but it is simply not implemented.”

“Chiang Mai is only going to expand,” continued Dr. Nawit. “Each sector must work together with the same vision and direction. The policies of the recent past have been haphazard and uncontrolled. We have said that we wanted to be hundreds of things; industrial city, green city, smart city, digital city, creative city and not to mention the hub of everything. This is a Thailand problem, not just a Chiang Mai one.”

“The world is moving rapidly, which is great. But technology can’t replace culture, history or lifestyle,” said Somwang. This charming city square we have should be cherished like a live museum. We need to pay more attention to our heritage and not just give way to commercial interests.”