“Families of most children in the centre are dysfunctional”

‘We Serve with Love and Care’; was the motto pasted above the front doors of the youth correctional facility located in a small village close to Mae Rim, a motto that suggested a striking difference from the portrayal of such centres in western media. British Borstals and American juvenile remand facilities have unerringly received bad press in the past, being depicted as housing abject young men and mercenary warders bullying, beating, being beaten, and birched in the gym. The centre in Chiang Mai, from the outside, could not have been less synonymous with this point of view. The many gardens surrounding the north’s only juvenile correctional facility were adorned with comic cement giraffes, pandas, wild geese; there were colourful flower beds, cartoon paintings and an all round pleasant air that hardly represented, realistically, cinematically, a facility where the north of Thailand’s most hardened young criminals were detained. Was this a ruse, an act of Dickensian chicanery to protect our eyes from the cruel truth that pervaded the grounds beyond the tall iron gates, where boys crafted ‘tools’ out of formally unemployed objects de violence and abused newbies in potting sheds?

Social worker Kornkanork Uttayothaand and resident psychologist Marut Kaewinsat talked to Citylife about a child’s life behind bars, their derailment, rehabilitation, and why most of these kids ended up in the facility. In total there are about six hundred detainees — aged 14-22 — at the moment with only forty four of them female — living in a separate compound — most of whom are in for theft and drugs, although some for more serious crimes including murder. Lengths of sentence vary depending on the judge’s evaluation of the child’s ‘background’. This did not always mean a history of criminality, more a general background of the child. They added that their facility was not a jail, it was a place of learning, their objective always education, providing the children with something for when they leave. The kids do have a fairly busy schedule. High school diplomas can be attained in the facility as can vocational diplomas and skills; there are many sports on offer, playing fields, courts, a gymnasium, and there’s time to watch TV and DVDs.

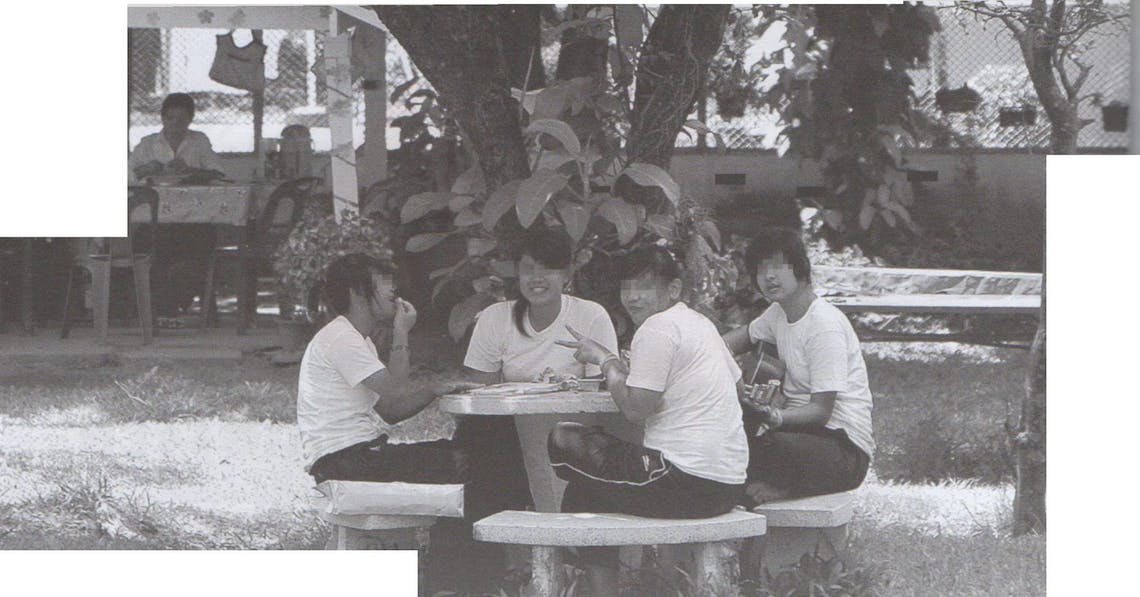

Kornkanork explained that most kids penitent and rarely cause any trouble in the facility; in the boys’ compound arguments flare but violence is usual- unheard of, “There are no bosses, maybe now and again a kid will want to try but there i just too many boys in there to fight,they usually stay in small groups.” On the subject of repeat offenders Marut explained that so kids do come back but most don’t. “We try and communicate with the children after release, ” the main problem, explained the psychologist, is the breakdown of the fan unit. Families of children in the centre dysfunctional, or more commonly, ruined by formidable triune of vice: alcoholism, infidelity, violence. “All these kids come 1 dysfunctional families, many have been abused — though a lot don’t want to talk about it – we try and counsel them, give them hope.” Most kids, he admits, are depressed suicidal, some are on medication from Suan Prung Hospital. “Some of the girls prostitutes before they came here, many on drugs or in gangs, not good environments.*

The two staff then said they would let US have a look inside the compound, see the sleeping quarters, the yard, and chat with some of the kids. Walking around the perimeter fence – an obstacle that could surely be scaled by an individual in the right frame of mind — Marut spoke of escape attempts, “The kids very rarely try to escape, why would they?… it’s not so bad in here and if they’re caught they’re sent back with longer sentences.”

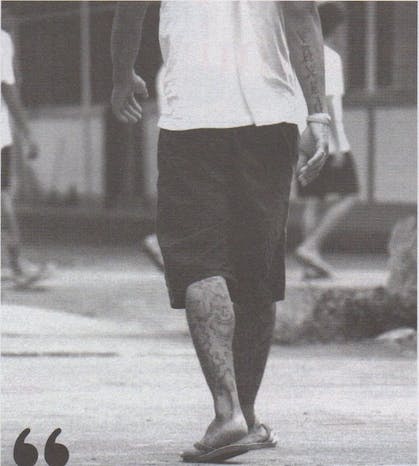

The first thing you notice when walking through the doors is that of the generic appearance of the kids: prison uniform of course — white t-shirt, black shorts, hut also every child had a dark complexion, most were thin or wiry, had short hair and many had Indian ink tattoos — and scars – scrawled over their bodies; an appearance in Thailand that is often defined by poverty.

It was evident that the social worker and psychologist were close to many of the children; the kids not only wai-ed, smiled and called out to the two staff, but Kornkanork was especially tactile with the younger boys and they seemed to appreciate her maternal endearments — although it was possibly a hindrance to the verity of statements put forth that the couple stayed alongside all the time I spoke to the children. The first child I spoke with, Ae, 15, had already served two years four months of his three year sentence.

Almost painfully shy, his head dropped in shame, he was at first reluctant to speak of his crime; Kornkanork tells him everything is ok and in a barely intelligible mumble he informs me, “I stole a bicycle.” Three years seems an awfully long time for a bicycle theft I told the two staff and they informed me that Ae had neither parents, nor a home, and the facility was the best place for him. Although he didn’t mention multiple bicycle pilferages, it is true — a Chiang Mai lawyer later informed me — that sentences are much more severe if the offence — even petty theft — has been repeated.

“Three years seems an awfully long time for a bicycle theft”

Bank, 20 years old, was also serving three years, but Bank’s crime was fighting while drunk. He told me that he was learning vocational studies, that he had no problems with his life inside the facility and wanted to be a soldier when he was released. He missed his family, his school and wanted to work and be good. At his side stood 0, 21, who was serving five years for aggravated manslaughter, he had shot a boy after an argument and the boy died. Like his friend he seemed somewhat constrained in his speech, he smiled wryly and informed me that he missed his home, his family and that he wanted to be a soldier. Unlike most boys their age they didn’t seem at all interested in girls, booze, fast cars/bikes or going to bars.

Bank swore he would never fight again. Unfortunately, for some reason, we were told that rather than see the boy’s sleeping quarters we would go over to the girls’ compound, which was “just the same” and see where the forty four girls bedded down.

The girls’ side was almost a picture of serenity, landscaped gardens, groups of hushed girls sitting, squatting, on the floor playing games or chatting — one girl, sat in a quiet corner of the graden is taking care of her child, which stays with her at the centre. Again the look of the detainees was generic, most girls were overweight — for Thais —, dark skinned; our photographer remarked that they all looked ‘maew’ hill tribe. Lay, 15, had served over two years of her three year sentence for keeping a stolen motorbike for her friends. She missed her mum and dad and wanted to study. When asked if she thought three years was possibly an overstatement she agreed and said it was too long. The next interviewee, rather more outspoken, was obviously embittered about being sentenced to five years. The girl, who didn’t want to state her name, was given five years for being an accomplice in a mobile phone theft, a long sentence, apparently, because one of the girls had a knife — that wasn’t used — while she waited on a motorbike for her friend to return with the phone. She had a child at home and said she missed her parents. “I go through all the moods in here, just like I would outside, but I am not happy about getting five years, it is

too long.” When asked if most of the boys and girls would get in trouble again after they were released – rather than live the life of honest, virtuous obeisance they all vowed to live – she replied, “Well it depends on their environment, if children have no family to take care of them then it’s hard to live a normal life.” Asked what she thought of the judicial system she replied disconsolately and with a hint of irony, “Nothing’s perfect.”

A far cry from the western perspective of a youth remand facility, the centre seems to be trying in earnest to develop the personalities of the kids rather than obscure them into abject indifference. Maybe some children were better off in there, that is debatable, but when two children both receive five years, one for an aggravated manslaughter, a murder over an argument, and another for being an accomplice in a mobile phone theft, questions ought to be asked. Marut’s impression of such haphazard and seemingly unfair sentencing is that some kids were made examples of, it was always up to the judge’s discretion and that could go anywhere depending on which war the penal system was currently waging. Also, as Marut constantly pointed out, “It’s the background that is important.” Children that have somewhat dysfunctional backgrounds fair differently from the ones that come from affluent, functional backgrounds, and of course very differently from those children whose families can afford expensive legal representation who can convince the judge that the child deserves no less than a stint banged-up in the monkhood or a stretch of nouveau riche psychotherapy? Some things haven’t changed so much since Dickens was alive, a certain number of kids seem destined to fall on hard times. As Marut often pointed out, “We are a learning centre, not a jail,” but this semantic nuance might mean little to the children who lose years of freedom for committing a crime that should really warrant no more than a slap on the wrists.

The Juvenile Correctional Facility would welcome any foreigners who can volunteer in teaching English or any other skills, academic or vocational. Also, if anyone would like to donate equipment to the centre please contact them.

Juvenile Correctional Facility, Regional 7 Chiang Mai 158 Moo 3 T. Mae Sa, A. Mae Rim, Chiang Mai 50180 Telephone and Fax: 053 279 043