‘Reassuringly potent, longer-lasting, available without prescription,’ might be an advertising slogan for Thailand’s up and coming public enemy number two (after ya ba), crystal methamphetamine, aka ice, or ‘ya aii’ as it’s called here. In small print on the back of each baggie there should be a warning, ‘can cause insomnia, loss of appetite, memory loss, seizure, psychosis and death.’

Having already decimated many American cities’ inhabitants of their teeth, money and dignity, (it’s thought that at least 1.5 million Americans are currently addicted to meth with about 12 million having used the drug in their lifetime) meth – which can be made using regular household chemicals with over the counter medicines (integral ingredient: pseudo ephedrine) and cooked up in the kitchen (lab) – has found a wolfish buyers’ market in Asia. Already with a stronghold in Japan and China meth, inevitably, is becoming increasingly popular in Thailand.

“I do it almost every night with friends, don’t sleep for two days, just smoke and play cards,” a pale, sexually alluring girl who works at the ‘higher end’ of the flesh service racket told me, “and I stay slim!” she said laughing, showing off her taut waist. The 21 year old then informed me she could get me some ‘aii’ – a gram – for 3,000 baht. Ice isn’t cheap, and in this girl’s case a well paid vocation is needed to address her burgeoning drug habit. Ice might be a lot more expensive than ya ba, but the effects last much longer and are much more potent, hence the rising popularity. A gram, for a new user, will go a long way.

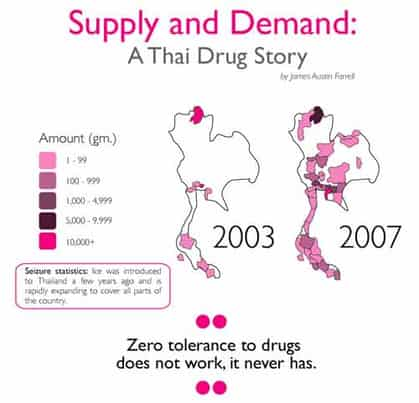

In 2008, 10 kilograms of crystal meth was seized in Chiang Mai, Thailand’s biggest ever haul. Seizure statistics given to us by Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Medicine’s Research Facility shows that crystal meth hauls over the last 5 years have risen dramatically. The first meth kitchen lab was found in Pratum Thani last year, moreover, in a brief interview with Pamela Brown of the Chiang Mai DEA, who is also interviewed in this month’s Citylife, she confirmed that crystal meth “has the potential” to become a problem in Thailand.

Dr. Paritat Silpakit, Director of Suan Prung Psychiatric Hospital, explained that for some reason, unbeknownst to him, drug abuse and mental health issues are seen in Thailand as two very different things, so anyone found to have a drug problem will not usually be referred to his hospital. “Universally,” he said, “these should come under the same umbrella.” He is very aware of the threat of drugs, especially crystal meth, though he also recognises the myopia in knee-jerk solutions such as the recent Wars on Drugs. “This was mostly an American

incentive from the 80s; Thailand received grants back then,” he explained, so the Thais might emulate Regan’s fanatically charged, and ultimately flawed, War on Drugs, “but it didn’t work in America and it didn’t work here.” Suan Prung research shows that the number of patients seeking therapy for methamphetamine abuse after the WoD had declined, though those seeking therapy for alcohol abuse rose alarmingly. Suan Prung and other organisations in Thailand are working on solutions to arrest the demand, not the supply. “People take drugs for all kinds of reasons, mostly to promote happiness and avoid suffering, so what we want to do is promote activities, give kids something to do.” On the bottom floor at Central Airport Plaza the national project ‘To Be Number One’ is addressing some of these problems. Kids can play various sports, learn artistic skills and join in activities _ they can speak to former drug users or even become lay counsellors. This is one way the doctor hopes to alleviate the drug problem, simply by creating more options for kids.

“Zero tolerance to drugs does not work, it never has,” he stated, though adding that Thailand has changed its zero policy stance. Four years ago the drug ‘rehabilitation law’ was introduced whereby a person found with drugs in their urine, with less than 5 pills, or carrying a weight deemed ‘personal use,’ would be treated by law as a ‘user’ or ‘patient’ not as a ‘dealer’. “You can enter a programme, or be put on probation, but you won’t be charged.” The way forward, he says, is to espouse the medical model, not the moral model, “we have to understand that many of these people are not criminals.” Each case will be sent to a committee consisting of medical staff and justice officials, in most cases small amounts of drugs will not warrant punishment. “This law applies to everyone, whether westerner or Thai or Burmese,” and when prompted about foreigners being threatened with jail for miniscule amounts of drugs (notably in Koh Phangnan or Pai) or made to pay large fines he replied, “You should know the law, it is most likely extortion by the police, for small amounts this should not happen. People have a voice these days; you can make complaints, official complaints.” But his real concern is not drugs, not the illegal kind, it is alcohol. “In this region we are having more and more problems with alcohol as the years go on, and if you don’t win the war on alcohol you will never stop the drugs problem.”

Rave On?

Dr. Apinun Aramrattana, assistant professor at the Chiang Mai University Research Institute for Health Signs and a prominent drug researcher, is a veritable oracle on drugs and drug abuse, savvy of the English E explosion and the US meth mania, as well of course, his hometown’s latent ice epidemic.

“Getting realistic statistics is hard, as ice is a drug common amongst people with money and if people seek treatment at private hospitals they have a confidentiality agreement. Police can give some statistics but more information must be known to understand the seriousness of the problem.” Though he is sure ice use is on the rise, and will continue to rise, especially when dealers inevitably start making the drug themselves in kitchen labs.

“We must think about three components: supply, demand and harm reduction. Supply is difficult to stop and sustain, the only way it can work is for police to work with communities, work hand in hand . . . we need to be mobilised.” In the countryside, in the villages, he explained, this is doable, but in the city it is almost impossible, so they are working on alternative preventive measures as well as limiting the accessibility of drugs. “Decrease of drug supply is short lived after a ‘war’ because it will always increase again, as we have seen in the past.” He believes the ‘rehabilitation law’ is a step in the right direction concerning how the law treats users, though with an air of cynicism he acknowledged, “the law, and the law on the streets are two different things.”

He explained that ya ba had a purity of only about 20%, most of it being caffeine, and regular abuse after 2 or 3 years would almost definitely lead to psychosis, though crystal meth has a purity of about 90% (in Thailand, US meth purity was at about 80-90% a decade ago, now it’s thought to be around 50%) – it seems a fair prognosis that if meth becomes as popular as he determines, Chiang Mai might be heading towards a troubled Crystopia. “Most kids don’t see the negative effects; it’s a relatively new drug. Statistically, abuse between males and females is the same, it’s very popular because it is a performance drug, so whether playing cards, cleaning, going out dancing or having sex, it enhances the activity. The kids love it . . . They don’t believe in psychosis, why would they?”

“There is a big market for meth that was already here with ya ba,” explains Dr. Apinun. Its high cost makes it very lucrative, more so than ya ba. He explained that it’s not expensive to make but its high price is a marketing strategy. “People with money don’t want cheap drugs, they will pay.” For Thailand’s growing parvenu the price of ice may not be cause for concern, though perhaps the high cost may prove a bane for the Thai prole, necessitating criminality in order to gain enough funds. Talking about the producers, traffickers and dealers Dr. Apinun exclaimed, “you won’t go bankrupt in this business.” The doctor thinks we won’t be able to eradicate future labs so we have to think more about demand. “The research into reducing demand is ongoing; we need mobilisation and more community structure.” As for harm reduction, there is no effective substitute for methamphetamine, unlike heroin, and ice use is notoriously difficult to stop and a full recovery is hard to achieve. “People need to be counselled, maybe by ex users, addicts need behavioural modification, this can take a long time.”

He doesn’t believe in a drug free world, “alcohol has been registered for 5000 years!” he quips, though he believes some drugs are definitely worse than others. “A drug free society is a dream,” he admits matter-of-factly. I detect he senses an aii-storm brewing somewhere in the Thai troposphere.