“Do you know when she will be back?” I asked.

“Not sure,” she replied sweetly.

I shrugged my shoulders and got to work. But a day turned into a week, and still no show. Something was up, and everybody at Citylife was feeling concerned. We found out later, from her mother, that the receptionist was on the run after her husband had brutally beaten her. She left the province to escape her husband’s violent outbursts. We were all delirious with worry, especially as the seriousness of the problem became increasingly evident: her husband began calling the office daily, even coming in once in a rather threatening manner to find out where she was. Of course, we didn’t tell him, and we wouldn’t have even if we knew where she went, but the experience left us all with a deep sense of powerlessness.

It has been a few months now and no one has heard from her. Not even her mother.

A Worldwide Issue

Though I am from Canada and know next to nothing about Thai culture, the issue of domestic violence is so universal that I can empathise. As I grappled with the disturbing nature of what had occurred right in front of my nose, my first thought was, “Does this happen a lot?”

And tragically, it does. One in every three women worldwide will experience violence from an intimate partner in her lifetime. Yes, one third of all women.

Domestic violence is an issue of taboo in many if not most parts of the world. Like bruises under a mask, it often hides in the shadows, concealed from the public eye. While the overwhelming statistics have, by now, made us rather numb to the horrors of domestic violence, every so often we are forced to witness it firsthand, and left shocked by its ugliness and outraged by the painful picture it paints. Take a look: In Pakistan, 943 women were killed in the name of ‘honour’ in 2011. In the United States, 40% of mass shootings in the last three years started with the gunman targeting his female partner. In Europe, women ages 16-44 are more likely to die from domestic violence than traffic accidents. Numbers can numb, but the reality is that there are countless human stories of bruises and brutality that never emerge from the shadows.

Thailand in the Spotlight

Thailand is not exempt from the global pandemic, as I learned. In 2007, the country passed its first-ever domestic violence law to protect victims abused by their partners. The act was praised for enforcing harsher punishments, more prosecutions and better protection for women. It also protects gay men and transgendered victims.

So here we are, six years later. Has anything improved?

From speaking with an array of social workers, NGOs, and police officers, I’ve found that the general consensus is uncertain at best. The problem is that while the law may theoretically protect, those responsible for enforcing it are not exactly enforcing or protecting. There is still a huge lack of understanding of both the law itself, and the necessity for such a law.

This is often the way of lawmaking anywhere in the world – it’s simply not enough to sign on the dotted line. In the case of domestic violence, especially in a macho society like Thailand, it requires entire societal shifts, whole scale education, cultural enlightenment and the rebooting of gender roles to really affect change. It’s not something that can happen overnight, or even in six years.

Crime and [Lack of] Punishment

Prior to the 2007 act, the majority of perpetrators served no time, received no fine and rarely went to court. Marital rape wasn’t even considered a crime in Thailand then, even though sexual abuse is known to be a common form of domestic violence. And on the blue moon occasion when a case was brought to the fore, the legal system pushed for family reconciliation rather than prosecution.

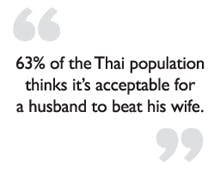

The exact rates of domestic violence are impossible to determine, but there are a few numbers we can work with. According to a report by the United Nations, up to 44% of women in Thailand have been hurt (either sexually or physically, or both) by their romantic partner, and 63% of the Thai population thinks it’s acceptable for a husband to beat his wife. It is perhaps that very attitude that elevates Thailand to number two among 49 countries for domestic violence.

All that was supposed to change under the new law, which now puts the onus on enforcement, rather than the age-old appeasement of negotiation.

Old Attitudes

Despite being given such powers, the police are still reluctant to intervene on domestic matters because many still see it as a private issue. The laws may have changed, but attitudes haven’t, which leaves the act dangling between stagnation and a moot point.

When I spoke to Usa Lertsrisantad, programme director of the Foundation for Women in Bangkok, she said it’s these intrinsic attitudes that have made her doubt the act’s effectiveness. “Many of the police officers are still family-oriented,” she says. “Their aim is not to protect the right of the woman but to protect the family.”

Because old habits die hard, and not fast enough, there haven’t been many domestic violence cases that have resulted in a conviction. A year after the law came into effect, the number of cases filed under the Juvenile and Family Court was a meagre 10. And when I asked Usa if she knew of any abusers who have gone to jail in recent memory, she chuckled, as if I was silly to have asked.

“There’s maybe a few cases, but most of them get compromised at the police or court level,” she told me.

Many NGOs criticise the law for putting the family institution above women’s rights. Without pressing charges, the victim and perpetrator can reconcile and return home at any point of a domestic violence claim, encouraged by a police force that is either naively well-meaning, criminally negligent or just chauvinistic. Whichever it is, they often believe that preserving the family unit is the ultimate goal.

According to Usa, this leaves a world of danger for women who end up taking the risk of returning to an abusive home. “There needs to be an intervention, or the husband needs to at least get treatment or do something so the woman can feel safe, not just come to the police, compromise, then return back again,” she says.

Seeking Safety

The other problem with the law – and again, these are endemic problems in many countries, not just Thailand – is that there are no measures for prevention. The law can only be enforced when a physical violation has actually occurred. If a woman comes to the police station and says her husband has threatened to harm her, there is nothing the police can do. There is no crime to report. Just a twisted take on the no pain, no gain trope.

Furthermore, this only applies if the victim will actually come to the police in the first place. Coming forth is the first step, and often the hardest, for victims of violence. Many women don’t ask the police for help due to a combination of reasons: afraid to speak up, don’t want to speak up, or worse, don’t bother because they know they won’t get the help they need. Even non-government organisations like Foundation for Women, which provides emergency assistance to abused victims, don’t get many calls. The organisations have to rely on their own volunteers to recruit vulnerable women.

What is needed, says Usa, is an environment where women will feel comfortable to come forth. And that begins at the first point of contact for most women: the police.

“It’s important in training to emphasise to the officers that they should refer the women to a shelter, or to a safe place,” says Usa. “I think that if there are more officers or social workers that get trained about this law, then more women will want to come forward.”

Currently, the Foundation for Women is seeking asylum for a woman who was convicted of killing her abusive husband after she tried to stop him from going out to drink, since alcohol had been a factor in his previous spurts of violence. For 10 years before that, she sought help from the police, looking for some form of protection from her husband’s abuse, but continuously got no support. Now she is in jail, facing a sentence of up to 15 years.

A New Type of Training

On 15th June 2012, a workshop was held for 285 third-year police cadets in Bangkok, where they received special training on ending violence against women. It was the first workshop of its kind. Both male and female cadets were given gender-sensitivity training on how to recognise domestic violence and how to use their role as agents of change to stop it. The workshop was organised by the Thai Police Cadet Academy and the United Nations as part of the UNiTE Campaign to End Violence Against Women, a crusade that has been outspokenly backed by Her Royal Highness Princess Bajrakitiyabha Mahidol.

One key element of the curriculum, which differs from the regular training of the Thai Police Academy, is that it goes beyond the law and its legalities. It emphasises a change in attitude and behaviour about domestic violence, aiming to eliminate the idea that family violence is acceptable. Cadets were trained on gender inequality and the social stigmatisation of victims, but above all else, the importance of women’s rights. The workshop even put faces to this oft-faceless issue, exposing cadets to real stories told firsthand by a victim and a former abuser. The training took place in the course of a day, while 80 cadets continued lessons for an extra two days.

Ryratana Rangsitpol, the Thai programme officer for UN Women, was at the event and spoke to ABC Radio Australia about its results: “We actually got some positive and encouraging feedback from [the cadets]. For instance, one of them said that what he got from the workshop was actually a new perspective _ a change of mentality on how domestic violence is not a family matter, not a private matter. If there are some women who really suffer from this, then there needs to be something done from the point of society and from the police.”

Since the domestic violence act passed, the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security has conducted one-day trainings for the police force throughout Thailand. However, the gender imbalance among the force might prove to be an issue, since female victims are more likely to report and pursue justice if they have access to a female officer. There are approximately 250,000 police officers in the country, and only 20% are women.

In Chiang Mai, there are only six female investigators among a total of 226. By mere probability alone, a woman who comes to a police station for help will be met by a male officer.

Breaking the Silence

While women have a hard time talking to police about domestic violence, the other end of the relationship also has its struggles. To get the full scoop, I met with Police Captain Jareewan Puttanuruk, one of the first graduates of Chiang Mai University to receive a Masters in Women’s Studies, and formerly one of the only female investigators in all of northern Thailand. Jareewan told me that the number of female officers is gradually increasing every year, but despite such efforts, she only sees one, sometimes two women a month who actually report an act of abuse. Imagine that. Just two. Considering the fact that nearly half of all women have claimed to be victims of violence, it seems that a whole lot are keeping mum.

For the few women who do come forward, police are generally confused about how to process their reports, sometimes filing them under the penal code instead of the domestic violence act, which provides additional assistance and rehabilitation to the victim and perpetrator. It’s sort of a catch-22. Women are afraid to report incidences to the police, and since few crimes are reported, police have no familiarity with how to handle them.

Ironically, the factors that make it hard for women to report violence and seek protection are the same factors that make it exceptionally difficult for police to work with them. It has so much to do with emotions, history, and familial ties, says Jareewan, that it becomes a very complicated matter.

“Once, we rescued a woman and separated the family for a week,” she told me. “But then the wife said, ‘I want to go back to my husband. I feel sorry for him.’ So we let her. You can’t just tell her, ‘No, you can’t go back.'”

Indeed, the overwhelming majority of victims are women, but let’s not forget that men are victims too, of violence but also of ideologies. Jareewan talked briefly about how the law is up against ideas of male entitlement so deep-seated it’s impossible to uproot, like telling a right-handed person to use his left hand. Thai men, like men in most cultures, are expected to be strong, manly and more powerful than women. If weakness ever shows, some men will feel shame. Mix that with the harmful effects of alcohol or drugs, and some men will automatically and continually resort to violence to reassert their power. It’s a destructive thought process that will take a lot of time to reverse.

Looking Forward

It’s a well-kept secret that the general lack of knowledge about gender-related crimes is rife among police and public officials. While gender training is becoming more and more available, it’s the female officers that tend to get targeted for the training because it’s believed they have more empathy and better social skills than men.

I asked Jareewan if she thinks domestic violence has improved in her 16 years of service. She tells me, with a tinge of regret in her voice, “We have more work to do.”

When the police captain, and recently even the prime minister, admits that implementation of the law has been slow, you know you have a problem. But in the face of this perilously rampant issue, there remains one bright light on Thailand’s horizon: a new generation of police officers with a new attitude on domestic violence. It’s a tall order, but if the feedback from last summer’s training workshop is anything to be believed, we can hope that the future, however distant it may be, looks promising.