Prasit Khrutharot hops off his Grab motorbike ride and waves. Wearing a t-shirt featuring a vibrant Vietnamese flag, covered by a short kimono hung loosely over scruffy jeans, he clutches his phone and sends off a quick message as he greets me – one of many messages received and sent over the course of our luncheon conversation.

Between mouthfuls of Japanese food, Prasit, 25, who goes by his nickname James, tried to explain why he has become the face of Chiang Mai’s burgeoning student protests, as well as having collected four court cases under his belt, most still ongoing.

“I was born to a very poor family in central Thailand,” said James. “We lived in a factory community with most families being migrant labourers, even though ours wasn’t. I saw from a very young age how differently they were treated and felt from a very young age that that was unfair. I had so many questions about how and why they were so oppressed, but there were no answers that anyone could give me. The real turning point for me was when my grandparents first received the 30 baht health care benefit during the Thaksin government. This changed our lives. Before we were always so afraid of hospitals, knowing we couldn’t afford them. This changed everything and as I saw my grandparents get healthier and stronger I realised for the first time that politics directly affect lives. This was when I began to watch political news.”

“The funny thing is that some of these yellow shirted teachers would give us books to read to shape our thoughts, not realising that these books became very important to us for the complete opposite of what they intended. We read the same books, but we interpreted them differently. That was fascinating. Sadly, many of those teachers don’t talk to me anymore.”

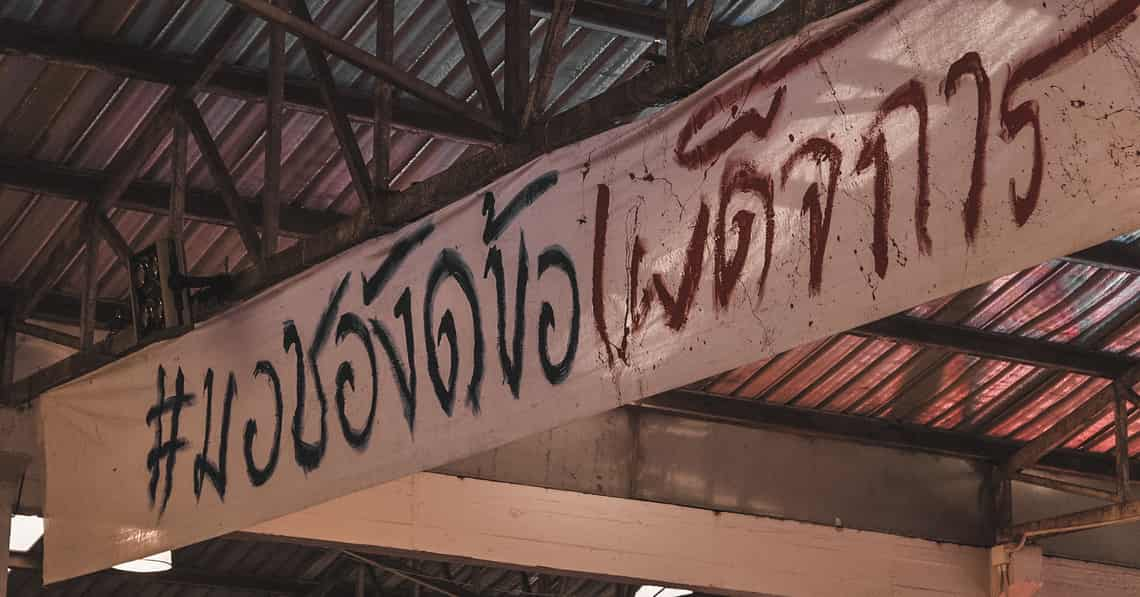

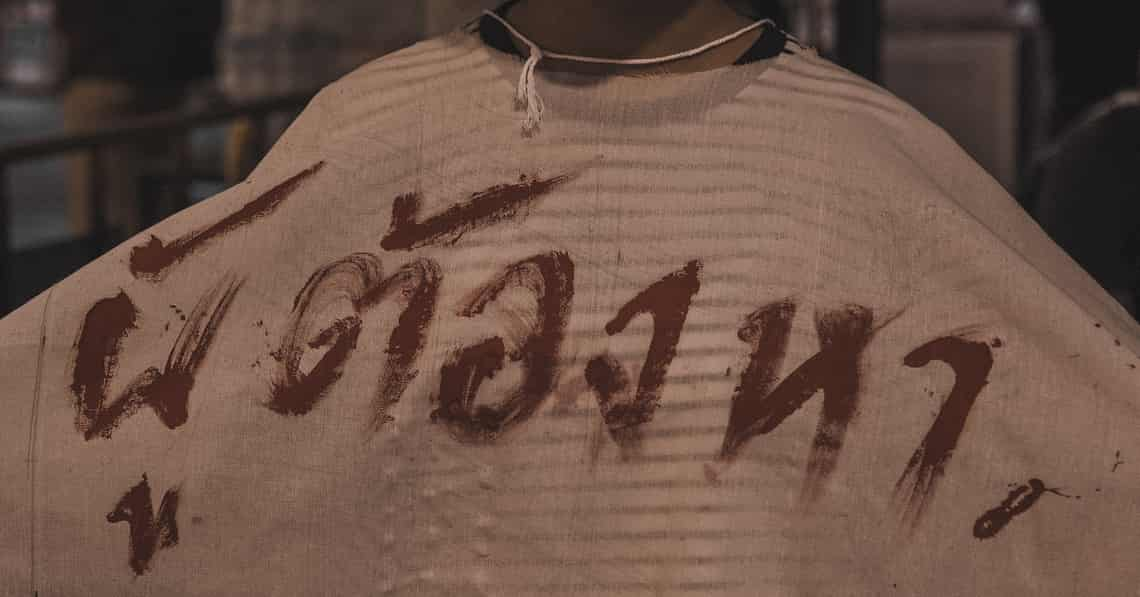

“I began to resist,” James said between mouthfuls. “I would put up posters, hand out fliers, it was all underground. This was post-coup and we had no right to do any of these things. It was signallng. As people were round up and arrested, most got scared, but some of us kept going. Quietly. It was not OK for us that these people who were simply speaking their minds, asking for rights, asking for justice, were treated this way. It hardened my resolve.”

At this time James changed majors from Chinese studies to history, taking a few years’ sabbatical for personal reasons in between.

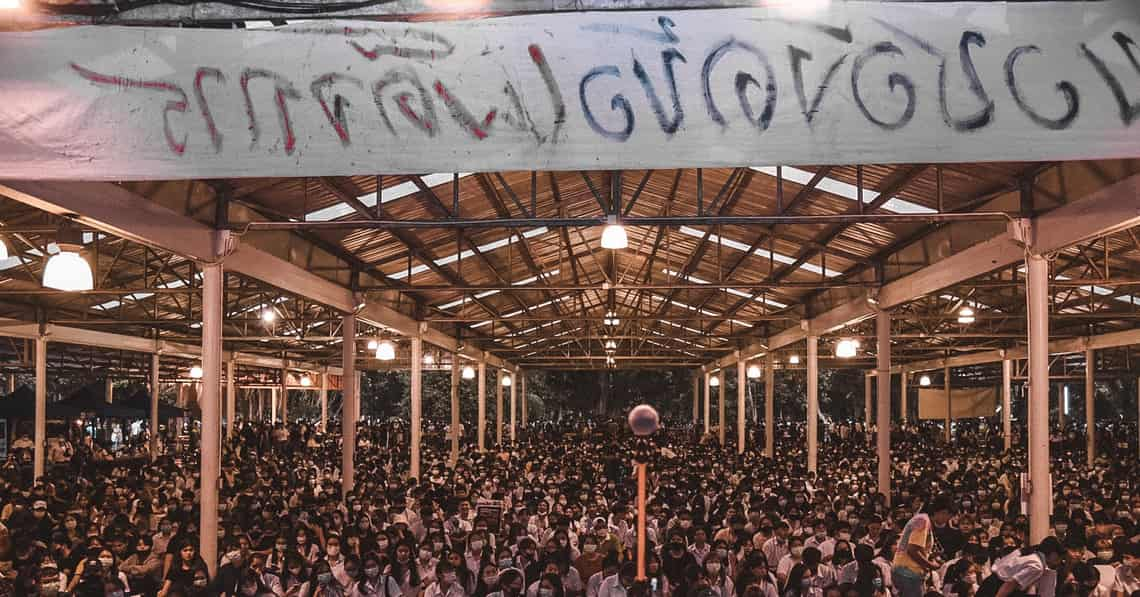

“We thought we were alone at first, but then our little underground movement began to connect with other underground movements. Twitter and social media wasn’t as powerful then as it is today, but we just slowly created a network. Most of it in the north has come out of Chiang Mai University, as other universities are not allowing their students voices yet. Some students get threatened with bad grades of fails, others demand students request permission prior to any political engagement. This is intimidation.”

James made his first public appearance in 2014, standing up on a stage in front of the university to decry the unconstitutional election, and getting into hot water for the first time for breaching the banned ‘public gathering’. He has had regular visits from the police ever since. “They appear friendly, they call or come round my place of work or class room to ask what I am up to, what I am organising. But it is intimidating when a large group of policemen come to visit.”

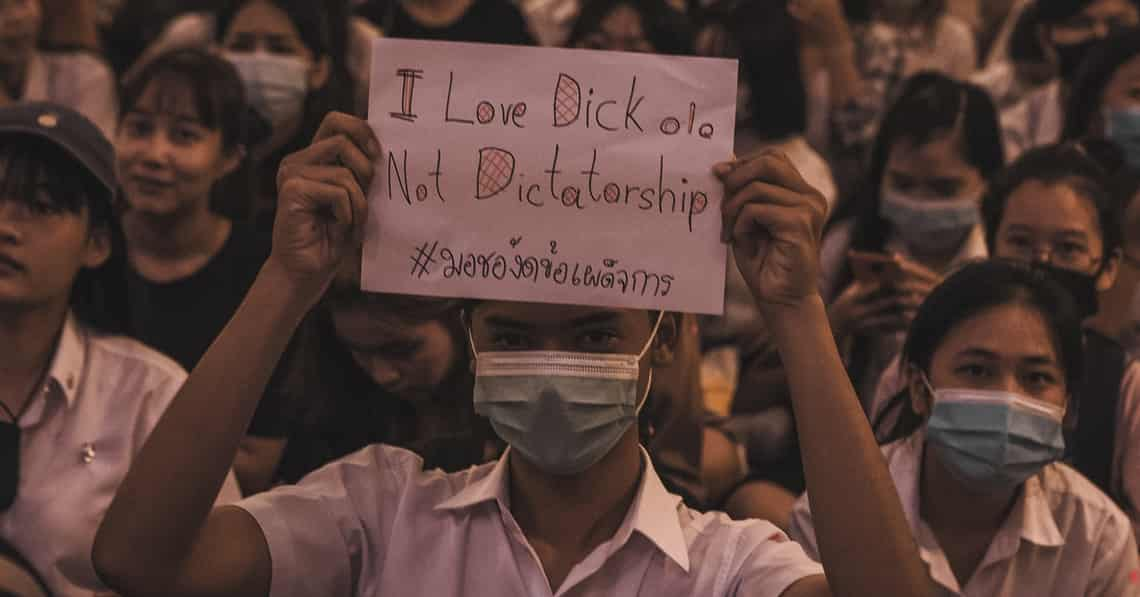

“The anti-junta political movement began to heat up again pre-covid,” said James. “But over the lockdown the Twittersphere exploded and hashtags which were antigovernment got stronger and stronger. Covid was our compress chamber that made people just say, ‘fuck it’. Our current national platform has come together through the joining of our collective hashtags. What is incredible is that it isn’t university students but school children who are the super spreaders of hashtags, as we tend to prefer to meet and organise offline, coming together through clubs, personal connections or classrooms. Children are not finding answers at school, and with the natural thirst for knowledge they have gone online to educate themselves, sharing reading material and information. Some of these kids are reading political, philosophy and history books and materials which most adults have never read. They are smarter than most of us and they are concerned about their future. These kids know how to find sources, fact check and then share information, much of which is showing them new and different ways of thinking and telling them that they have a right to speak up. Some lean towards Marxism, some are liberals, others anarchists and even conservatives. They are savvy, they are smart, they had time over the lockdown and they have power. Years of frustrations over the violence and ignorance by their teachers and school admin have led to this. It all started with the need for education reform which was and is the children’s main platform. The authorities are not happy at all right now with the children, they see them as antiestablishment, anti-everything that they are being taught and told to believe. And they are right. Sadly, it is the adults who have suffered from Thailand’s poor education system and they can’t conceive that we have minds of our own because we now have tools to educate ourselves.”

“It is the adults who have suffered from Thailand’s poor education system and they can’t conceive that we have minds of our own because we now have tools to educate ourselves.”

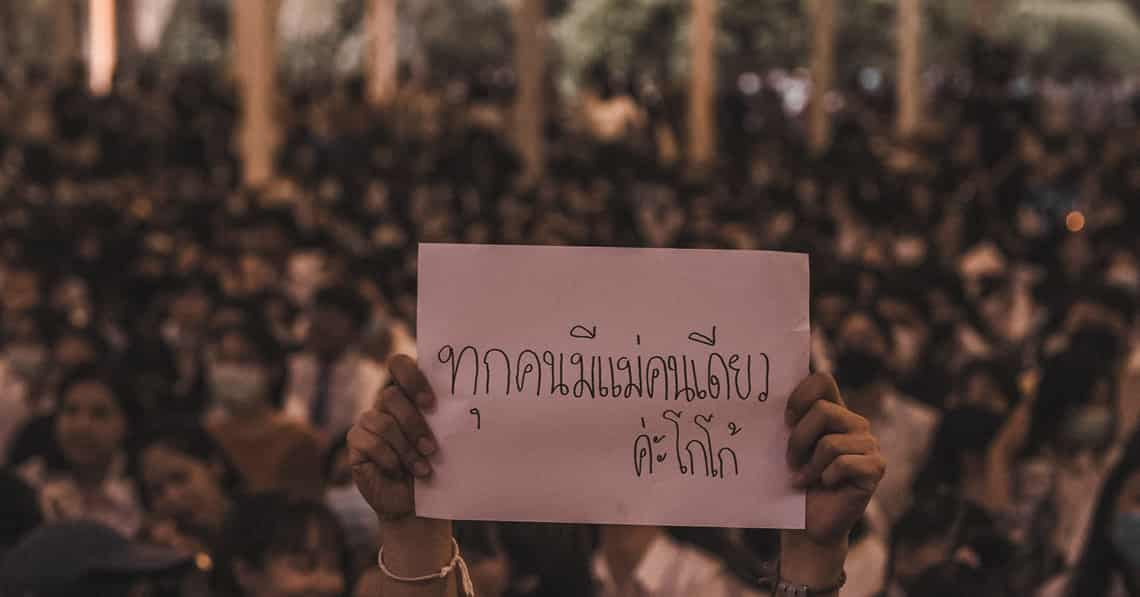

James says that he sees the current rise of the anti-government movement as a human rights movement.

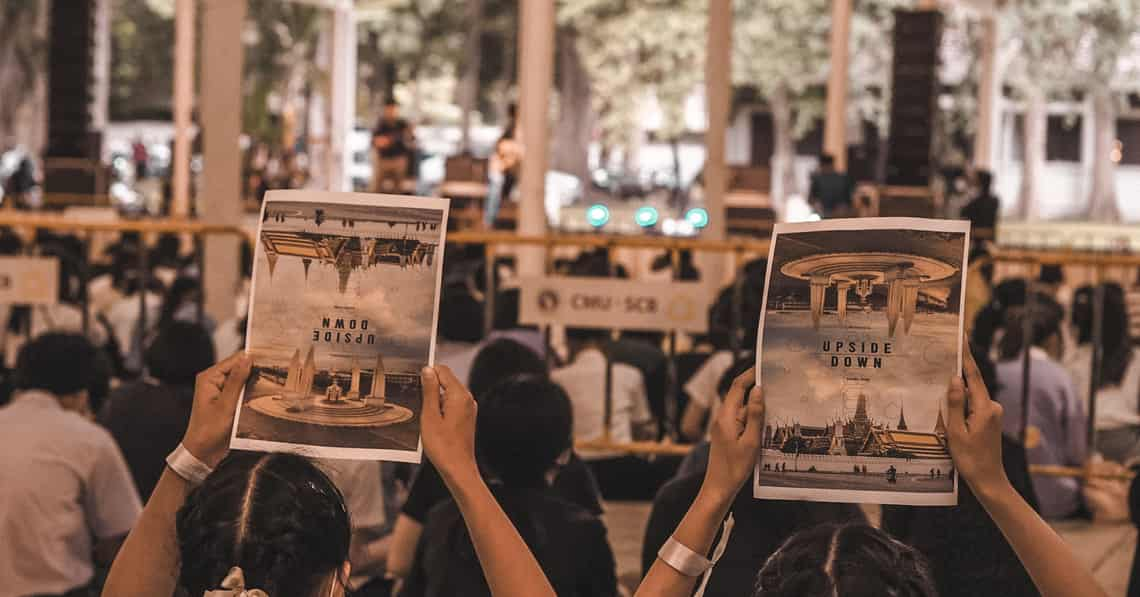

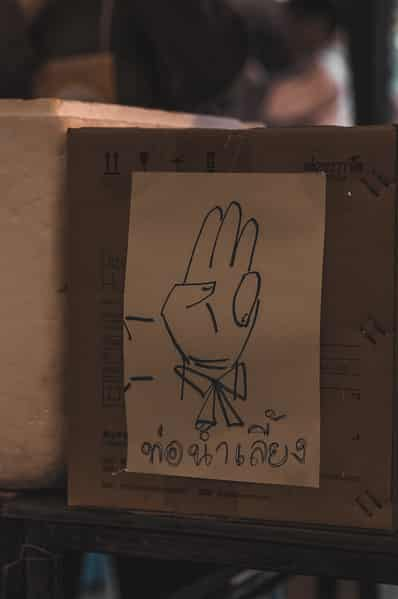

“That is all anyone is asking for,” he explained. “The children want a good educational system which isn’t corrupt and mired in authoritarianism and an unfair power structure. For many of us we can’t tolerate an establishment which doesn’t accept the mechanics and systems of parliament which has checks and balances. Because they couldn’t function under a constitution, they held a coup and tore it up. They didn’t allow for democracy to find its own way. For others, such as LGBT groups, migrant, women’s, handicapped, ethnic minority groups, they all have their own grievances, but it all comes back to the same agenda. They want their rights under a democracy.”

“Thailand’s current climate doesn’t allow for voices to be spoken,” he continued. “Bangkok is the main space with the largest voice reserved for the conservative middle class which the government appeases by indulging. We just want to be heard and represented too.”

“The constitution needs to be the highest thing in the state. It should be the frame within which we all function freely. Can we also just take care of the people first? Make sure we are OK? Then the monarchy or the army or any other institution can have its place. We can coexist. We just want to have rights too.”

James is resentful of many critics of the movement who are using the monarchy as a tool to silence dissent, falsely claiming students wish to topple the institution. He said that it is all interconnected, and it is a discussion which needs to be had, but if all institutions can co-exist under the constitution then that would be ideal.

“What we are saying is pretty much common sense and reasonable, there is nothing radical going on,” said James. “But they won’t listen to us. They choose to imbibe what reaffirms their point of view. They are saying that children are being brainwashed. You try brainwashing these kids! They would catch on immediately and wouldn’t put up with it!”

“We have hope. We have to keep moving onward, open channels for discussion. While so many are obstinate, there are signs that some at top levels are beginning to listen. People who were hard are softening. This means a lot. Look, we can’t go against society. But we are hoping to create a new society for change.

Next step. Expand network, and educate the public.

“I believe we can do better and get better,” he continued. “This is a wonderful country in so many ways. We are a resilient people and we have accepted so much oppression over the years. We just want a just society.”

James doesn’t see the immediate future of the movement shutting down airports or locking down Bangkok as the previous decades’ protesters did, but finds it more appealing to create pop up mobs which can be easily dismantled and moved around.

“Imagine if small groups all across Thailand just grabbed a microphone and started speaking in public,” he continued. “First off, they will have their power dispersed too, so it’s safer for us, but also we would be heard by so many. I want people to realise that what makes society stronger is awareness. Human rights is our rights, no one gave it to us, we were born with it and people need to be aware of this. We don’t all have the same ideology, we just want a platform of governance which will protect all of our beliefs and rights.”

“What is worrying is that right now our movement is benign and reasonable,” he concluded as we finished our meal. “But if no one listens to us, if they crack down on our freedom of speech, there will be some people who will harden, become extreme. This could lead to trouble. So let’s start having a conversation and see what we can build.”

If you wish to support the student movement, follow their (Thai language) Facebook page or go further and donate towards their cause. The money will go towards sound systems, fliers, pamphlets, posters, souvenirs such as stickers and pins for protesters and organisational costs.

👉 074-1-52180-6 👈

นางสาวภัคจิรา ทรงศิริภัทร และ นางสาวภิญญาพัชญ์ แท่นงาม