When hearing the name Bo Sang, those who have lived in Chiang Mai long enough might nod and say ‘yeah, they make umbrellas,’ as a TAT postcard-image of the colourful painted paper umbrellas that used to be one of the city’s most ubiquitous cultural symbols, floats to mind. A few decades ago, kaleidoscopic Bo Sang umbrellas would be daintily held by some of the most beautiful women in Chiang Mai as they appeared at every major town event. Some may remember the heady days of the 1995 Southeast Asian Games, when the event’s mascot was a cat holding an umbrella, a symbol featured on all of Chiang Mai’s marketing and branding collateral for years to come. In fact, the actual mascot itself was only removed from the 700 Year Stadium, built for the occasion, a couple of years ago. As a plethora of exciting new products and souvenirs have flooded the market, the jaunty Bo Sang umbrellas appear to have faded from our minds, slipping into the past. Citylife therefore decided to take a look this month at what was once one of the city’s thriving industries and symbols and see where they are today.

The Bo Sang umbrella is not just the product of a superficial promotion. Although there is no official record of its origins, it is believed that its craftsmanship could be traced back as far as two centuries. The origin of the Bo Sang umbrella is mentioned in a popular local myth where, according to the tale, Kruba Intha a wandering Thai monk from two centuries past, went on a pilgrimage near what is now the border of Thailand and Burma. There, he was given an umbrella by a Burmese person who came to make an offering. The monk was so impressed by the umbrella’s quality that he traced it back to the village where it was made. After he succeeded in learning the craft, he returned to his hometown (present-day San Kamphaeng District, Chiang Mai) and spread the knowledge and skill to his community.

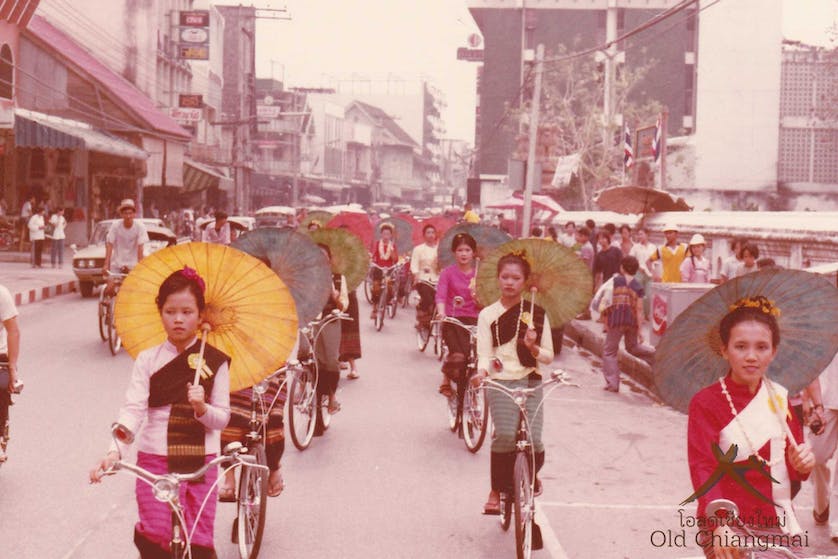

In 1976, the Old Chiang Mai Cultural Centre (now renamed Old Chiang Mai) held an event which was, effectively, the first to introduce the umbrellas as a cultural symbol of Chiang Mai. “Mae Ying Kee Rod Teep Kang Jong (Woman Riding Bicycle with Umbrella) was my grandmother’s idea,” said Manaswat Chutima, Assistant Managing Director of Old Chiang Mai and the third generation running the centre. “She was inspired by her childhood memory of seeing women riding on the bicycle while holding an umbrella on the other hand.” The event, which comprised a parade down Tha Pae Gate heading towards the centre, was exactly as her grandmother envisioned. Each district across Chiang Mai would send their candidates to compete in a beauty contest where each contestant had to participate in the bicycle parade dressed in full Lanna costume with, of course, a traditional umbrella. “I mean, it was quite a skill, wasn’t it? Riding in the Lanna pasin is hard enough and they had to hold the umbrella too, it’s impressive. And it was quite a distance too,” said Manaswat, as she shared an old photograph of the event. The contest grew larger and became one of the biggest annual events on Chiang Mai’s calendar, comparable in attraction to the historic Songkran Festival. “It became a big thing where all hi-so rich people and many big names people in Chiang Mai participated. The crowned beauty who won the contest would be such a pride for her district,” said Manaswat, who explained that the contest later expanded to include foreigners for the fun. For 10 years, the Old Chiang Mai Culture Centre hosted the event before handing it over to the Chiang Mai Municipality.

It was the following year, in 1977, that the Umbrella Making Centre was founded in Bo Sang. “My father saw that these umbrellas were attractive to tourists, but feared that the tourists may not find it convenient to search through the village for houses which made or sold the umbrellas,” said Kannika Buacheen whose father, Dr. Thavil Buacheen, founded the centre. “Many of the umbrella craftspeople had left their skills to dust or shifted to other crafts like woodcarving or furniture making, which was more profitable. With concern that skills and knowledge may one day die out, and understanding that tourism needed something tangible, my father aimed to turn the small cottage industry into something more beneficial to the entire village,” said Kannika. “So in 1977 he started to bring visitors to the craftpeople’s houses where the umbrellas were made.” Kannika explained that while the idea was intriguing, it was not very practical. “The villagers only made the umbrellas in their free time between farming and other things they do in their daily lives, so it was a failed attempt…The project had no one to present the craft,” Kannika explained. Still, there was an even more intractable logistical challenge. Because a whole community participated in making one umbrella, each devoted to only one element, visitors would be required to stop at every craftsperson along the process. This proved unrealistic. A year later, the Umbrella Making Centre gathered all the resources into a single location. “Our focus is the welfare of our craftspeople while preserving our cultural heritage,” said Kannika. The centre, which started out with 12 craftspeople, now has over a hundred people under its wing. The centre was integral in building Bo Sang village up as a cultural tourism destination where visitors can either observe or get a hands-on experience in making the distinctive sa paper umbrella. Through the centre’s efforts, the sa paper, made from a native plant, also became well known.

In 1982 the village collaborated with the Tourism Authority of Thailand and local authorities to found the Bo Sang Umbrella Festival, which eventually adopted the bicycle ride idea along with the beauty contest, calling it Miss Umbrella. The title was later changed to “Miss San Kamphaeng” which has morphed into today’s “Miss Chiang Mai” event, held at the annual Winter Fair.

Unfortunately, the village is no longer as popular a tourist destination as it once was. Orasa Boonlit, one of the shop owners in Bo Sang who has been operating for over three decades, revealed to Citylife that for the past five years she has been having a tough time with the stagnant economy due to the decreasing number of tourists. The Umbrella Making Centre is also struggling with the decreasing income. “Three years ago we exported up to 80,000 umbrellas earning approximately 10 to 15 million baht. Now, the figure downs to 8 to 12 million baht a year,” Kannika noted. Small retailers in the village, such as Bangon Uthama’s shop, said that the profit per umbrella is only around 3 to 4 baht.

Declining profits and changing trends put the craftsmanship of Bo Sang umbrella at risk of disappearing. Upon a recent visit to the Umbrella Making Centre, Citylife learned that the youngest craftsperson in the Centre is now 40 years old. Walee Jaijoy, 58, who has been working for the Centre for over three decades, said that majority of the craftspeople send their children to study in town and hope for them to be better off with a higher level of education. “We might have our kids work here during summer break but then they just grow out of this place,” said Walee.

“I’ve tried to cooperate with a school in San Kamphaeng to include the umbrella crafting knowledge…but with complication of their system, I failed to do so,” said Kannika.

Around the world, many forms of traditional craftsmanship are at risk of vanishing without a new generation of craftspeople and a receptive market to sustain their craft. However, the story of the Bo Sang Umbrella is not finished. Despite its decline, there are people fighting against the odds to preserve this special part of the city’s cultural heritage. The Bo Sang umbrella is waiting to thrive again, as one of the elements of our unique identity.

Perhaps with some innovation and savvy marketing, the tired Bo Sang brand can be resurrected. In fact, in June of this year New York Magazine published a story featuring a trendy new ‘wearable art’ umbrella by Lily-Lark which also features a UPF 50+ coating which they say is made in Chiang Mai, we presume (and hope) by Bo Sang’s many talented craftspeople. It may be time for a Bo Sang brolly renaissance.