One of the most distinct illustrations of gender inequality in Thailand is found in its most entrenched institution: religion. In her fascinating new documentary, White Robes, Saffron Dreams, acclaimed filmmaker Teena Amrit Gill explores the discriminatory treatment of women within Thai Buddhism, a topic that has gone largely unexamined in the past.

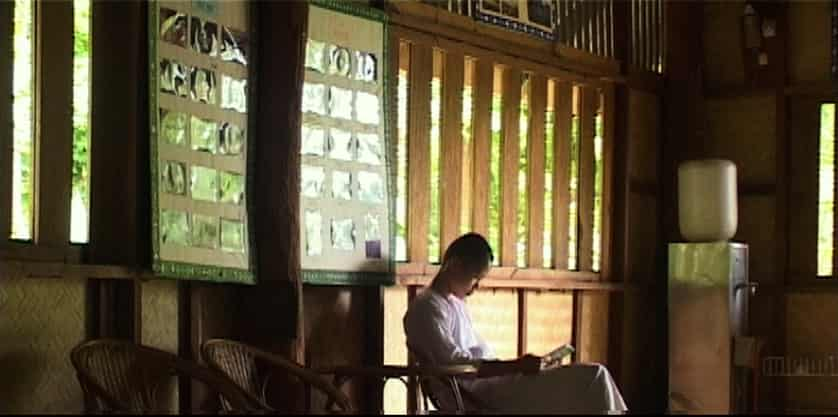

The 43-minute documentary, which was released last year and is currently on the festival circuit, follows the story of a Buddhist monk and a Mae Chi (Buddhist nun), and explores the sharp difference in opportunities for males versus females in Thailand, a country that is 95% Buddhist.

Indeed, boys who cannot afford to attend public schools due to the cost of books, uniforms and transportation, always have the opportunity to become monks and receive food, shelter, and education (which can go all the way up to university, masters and PhD programmes) for free. Impoverished girls, on the other hand, are left with virtually no options as they are barred from being ordained. In the film, we visit one of Northern Thailand’s tragically few nun’s institutes in Lamphun, which has now sadly been all but shut down due to lack of funds.

Filmmaker Teena Gill, who shot, scripted and directed the documentary on her own, without any outside funding, has a background in gender and development and a long-held interest in Buddhism’s patriarchal inequalities. Gill was born and raised in India but lived in Bangkok and Chiang Mai for 11 years as a journalist and filmmaker. She spent over a decade working on White Robes, Saffron Dreams, which she says allowed her to really understand the lives and backgrounds of her subjects. I was able to meet with Gill, a warm woman with a soft-spoken but powerful presence, to learn more about her experience making the film, and the issues she hopes it will bring to light.

“This was a very difficult film to make, not just because I was an Indian filming in Thailand, but also because nobody wants to talk about these issues,” Gill told me. “It’s very difficult to challenge the status quo in Thailand. The risk is very high.” However, she says, there is now a growing movement of women willing to confront the deep-set patriarchy that has come to characterise Theravada Buddhism over the centuries. In the documentary, Gill introduces us to Thailand’s first Bhikkhuni (a fully ordained female Buddhist monastic) of modern times.

Ordained in Sri Lanka, Bhikkhuni Dhammananda is a scholar and a leader in the growing movement to bring gender equality back to Buddhism. Since her ordination, close to 80 other Thai female Bhikkhunis have been fully ordained, along with hundreds of novice nuns or Samineris. But the Buddhist Sangha has strongly resisted and denounced the inclusion of women in this male-dominated world, and the general public seems vastly uninterested in helping girls get an education equal to that of boys. Today, as the film explains, there are 10 to 20 thousand Buddhist nuns living in Thailand. Most live in temples like the monks do (in their own separate quarters) and can shave their heads and wear white robes (never saffron). However, the nuns are given only eight precepts (versus the 200 or so that monks receive) and their main role is doing domestic chores. “Mae Chi don’t have much freedom,” added Gill. “80 percent live in temples where the monks are in charge, and occupy very traditional roles such as cooking and cleaning.”

Meanwhile, as Buddhist activist Ouyporn Khunkaew points out in the film, these nuns are often subjected to abuse from the monks, which they endure thanks to a deeply entrenched belief that they will continue to make merit and be reborn as a man in the next life. In this life, however, they have no standing in Thai society, are not accepted by the Buddhist Sangha and have no legal status to speak of. It’s a pretty black and white picture (or should I say, saffron and white) of inequality. But where did this come from? “Buddha himself acknowledged that there is no spiritual difference between men and women,” said Gill. “Back then, around the third century B.C., there were actually many female spiritual leaders, including Buddha’s own mother. But the society in which he evolved was already very patriarchal. These dynamics of power go back so far. The moment there’s an opportunity to challenge female leadership by men, they’ll take it.”

Indeed, the film points out that in 1928, the daughters of a radical monk in Thailand decided to be ordained as Bhikkhunis. But when the powers that be found out, the women were forcibly disrobed and imprisoned, and a law was passed officially outlawing the practice altogether. Allowing this kind of patriarchy to infiltrate Buddhism has created an unwinnable situation for Buddhist women, who are told that just being born female in the first place is the result of bad karma from a previous life. As Gill and Ouyporn note, this is why it is usually women you see in temples and out on the streets making merit, so that in the next lifetime they might be lucky enough (or “good” enough) to get reborn as men and eventually reach nirvana. “As I worked on this film, I felt that the more this whole attitude toward women is projected by Buddhism, the more misogyny exists in society,” said Gill. “If you use religion as your argument, you leave no room for discussion. If you have a whole society that believes this is the truth, then what are your possibilities of moving away from that?”

DVDs can be purchased directly from Teena by emailing teenagill06@gmail.com.