You can see it from every vantage point in Chiang Mai’s Ping River basin, the sun sets somewhere beyond its ruffle of peaks to the west, it leaks dozens of waterfalls and streams which gurgle down to the thirsty valleys below and the people of Lanna look towards the glittering golden pagoda, which appears to be at its summit, as one of the most sacred sights in the north of Thailand.

Doi Suthep-Pui National Park has often been likened to a blessed green lung, pumping and breathing its oxygen onto the polluted concrete jungles of Chiang Mai city below.

The mountain gives.

Treasure trove

Doi Suthep-Pui National Park covers 160,000 rai of land (261 square kilometres). It contains more orchid, bird and butterfly species than Kao Yai National Park, which is eight times its size. A study of monsoon forest on Doi Suthep showed that it has more tree diversity than any tropical deciduous forest, bringing it closer to that of a rain forest. The national park is also home to over 350 species of birds. To put this number in perspective, the entire continent of Europe has 700 species, the United Kingdom and Doi Inthanon (which covers more altitude) each are home to around 400 – being within yoo-hooing distance to the city, this is a bird watcher’s paradise. One fourth of Thailand’s 1000 orchid species can be found on the mountains, fifty of which the International Union for the Conservation of Nature has declared to be endangered. This park has also seen more species discovered than in any other protected area in Thailand, with over 320 new species of plants and 200 new species of animals having been discovered to date.

“While bears and other large mammals have long since left Doi Suthep, you would be surprised at the number of wildlife still here,” said Hans Banzinger, of the Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Agriculture Department of Entomology, who conducted his first research on Doi Suthep 41 years ago. “There are lots of small mammals remaining, and if you are lucky you can see flying squirrels gliding through a moonlit night, hear barking deer at dusk, glimpse an occasional wild boar or leopard cat deep in the jungle and, if you are really lucky, catch sight of the one monkey family remaining. But these are rare sightings; the majority of small animals are frogs, reptiles and bats, all of which are essential to seed dispersing and an integral part of the ecosystem.”

Rungsrit Kanjanavanit, cardiologist and President of the Lanna Bird and Nature Conservation Club says that Doi Suthep is attracting more and more bird watchers, with 300 members in his club alone and five to six international bird watching tour companies regularly bringing watchers to the mountain. “Birds are essential to the national park, they pollinate and act as gardeners, planting seeds,” he explained. “One exciting development recently is the return of Mrs. Hume’s Pheasant, sighted for the first time after a thirty year absence.”

From past to present

Geologically speaking, the mountain is ancient: the granite was formed a mind-boggling 330 million years ago and was heaved up with the Himalayas around 50 million years ago. But let’s fast forward a few years…

Legend goes that in 1386, about a hundred years after Chiang Mai was founded, a white elephant carrying a relic of the Lord Buddha himself was set to roam. It immediately made its way up the mountain, finally lying down to rest at the auspicious site that is the Doi Suthep temple today. The temple, and the mountain on which it lies, took its name from the hermit Suthep, the son of Pu Sae and Ya Sae, the cannibalistic giants who roamed the mountains in ancient times, and for whom a gruesome appeasement ceremony is still held every June at Mae Hia District. The temple has been considered sacred by the people of Chiang Mai ever since and is one of the twelve temples which must be visited in the north by pilgrims.

The Phuping Palace was built as a winter home for the current monarchy in 1961. The Doi Suthep-Pui National Park was established in 1981 by the Royal Forest Department (which changed into the National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department in 2002). Opium was officially banned from the mountain in 1958 (though according to authorities it secretly continued to be grown until 1991!)

“This sacred mountain is at the heart of Lanna people; it’s not a tourist attraction, but a historical, cultural and environmental inheritance.”

Patcharin Sugunnasil of the ‘For Chiang Mai Group'

Green lung getting cancer

We naive residents of Chiang Mai have often been told of reforestation programmes, check-dam systems to retain mountain water, eco-friendly and sustainable tourism initiatives and other mouth-filling rhetoric. Few of us have ever questioned what we have been told.

“I call this eco-pornography: though the government claims 25%, satellite imaging shows that only 10% of Thailand remains forested.”

James Franklin Maxwell

In fact Doi Suthep is ill. Very very ill. According to James Franklin Maxwell of the Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Science Biology Department, who has been studying the mountain for over 20 years, only 25% of the national park’s 160,000 rai is healthy forest, the rest is at best, secondary growth; at worst, developed. Maxwell also warns of dire consequences if (lack of) water resource management continues the way it is, and over population of the mountain range remains unchecked. The great green lung which we have depended upon for so long is gasping for breath and it won’t be long before this tide of overdevelopment does irreversible harm.

The problems are myriad and so great that I shall have to go through (some of) them one at a time.

So many people

According to a 1999 ranger station chiefs’ report, around 5000 people live on the Suthep-Pui National Park land…today’s numbers would be much higher.

Visitors going up the national park via Huay Kaew Road number an average of 160,000 per month, 120,000 of whom visit the temple

The abbot of Doi Suthep temple, Phra Thep Worasitajarn, says that around 120 monks, nuns, novices and workers live in the 60 rai temple grounds, while the Doi Suthep Village which rims the massive temple car park is home to 620 registered villagers, claimed Sompong Paphonpat, the village head. Not everyone agrees on the numbers however, and Surachai Tuamsomboon, Superintendent of the Doi Suthep-Pui National Park – the man who is ostensibly in charge of the entire national park – says that in high seasons this number easily swells to 3000. The Phuping and Hmong villages contain quite a few hundred people and no census has been made on encroachments on various foothills.

Where have they come from?

Surely you are as incredulous as I am in wondering how on earth these people managed to put their roots down in a national park. Sure, the four Hmong villages predate the formation of the park, some having been established over a century ago. Sure, with the Phuping Palace and the temple requiring staff, these people must be housed. Sure, some rich locals managed to grab a few parcels of land pre 1981 and dotted around areas such as Pa Laad Waterfall are still some of these run-down houses. But thousands upon thousands?

According to Sompong, Doi Suthep Village Head, most of the 620 registered villagers are not local. He, as village head, and reporting directly to the Suthep Sub-district Administrative Organisation (SDAO), oversees 90 square kilometres of land, 35 of which is residential, and was granted to the village by the government in 1992. “We are citizens with no rights; we have no chanote (land deeds) and can’t take out loans from banks. We manage a budget set by the government and do our best to support the tourists and visitors to the temple with our 30 restaurants and other businesses.”

Not so, says the Surachai, the Superintendent of the national park. “Once the land was given to the village, we lost all jurisdiction over it, and this is why it has been allowed to become the slum it is today,” complained Surachai. “The government built commercial buildings and housing for the village and initially they each paid rent of 600 baht per year. However, we didn’t have a system to collect rent until 11 years ago, so the villagers soon cottoned on that without official receipts, they could get away with refusing to pay rent. Then once we were able to collect rent, people had changed residences so often that the lack of paper trail allowed the entire village to continue to live and earn a living rent free until today. So when they ask to become legal owners of their land so they can take loans, I want to know what they have paid to deserve such ownership.” Not all villages are stubborn however, and Mae Sa Mai and Phuping villages both pay rent, thereby being given documents from the government which allows them to take out loans.

Basically the national park, while having the law on its side to enforce its policies, loses any control once land within its territory is handed over to another department or organisation, and their role is relegated to that of advisor. “Whether it is this government demanding us to slice off 819 rai of land for the Night Safari, the Chiang Mai University taking land for ‘research’ purposes or the Highway Office wanting to build another road through the park, we have no say,” continued Surachai, “while the law is on our side, we have no muscle to enforce it. If we step onto too many toes we get transferred.”

Everyone means well

“The first phase of the Night Safari is now 100% Plodprasob Suraswadi, Natural Resource and Environmental Ministry Permanent Secretary, told me proudly. “Within the next year and a half we will also complete the planned elephant camp and the 8.5 kms cable car project. It will be wonderful, Chiang Mai World will be like Disney World, but based on culture and the environment.”

Chiang Mai World project, of which the 819 rai Night Safari is part, intends to expand to 23,000 rai, taking a whopping 14% of the entire Doi Suthep-Pui National Park according to Plodprasob Suraswadi, Natural Resource and Environmental Ministry Permanent Secretary

So far, claimed Plodprasop, 1.6 milion people have visited the Night Safari since its opening seven months ago (averaging an astonishing 7 thousand visitors per night).

“I want to tell conservationists that I am not a monster,” insisted Plodprasop, “I have been responsible all my life for our evironment which I love. I work within the rules and regulations set down by the national park department. Just becuse people criticise what I do doesn’t make them as dedicated as me, I do the hard work.”

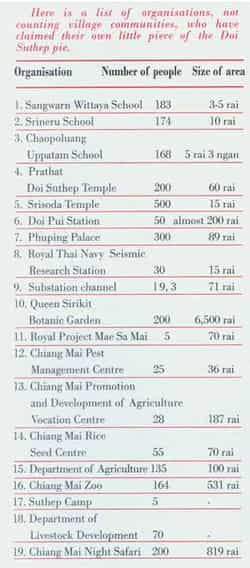

Here is a list of organisations, not counting village communities, who have claimed their own little piece of the Doi Suthep pie.

So what is the problem?

Jurisdiction.

The Chairman of the Suthep Sub-District Administrative Organisation (SDAO), Karun Khlaiklueng, who manages infrastructure for 21 square kilometres of land in the national park, covering such famous attractions as Montatarn, Huay Kaew, Wang Bua Ban, Pa Ngerb and Pa Laad waterfalls and the Doi Suthep, Hmong and Phuping villages, says that he is responsible for around 3000 people who live in the national park. With his 60 million baht per year budget, he collects their garbage and taxes, supplies their water and electricity, educates and hospitalises their needy and acquires the budgets to build their roads. “The main problem that I can see is legal,” he said. “It is all too complicated. There are many laws: the forestry department has its own laws, the fine arts and religious departments, which look after old and new temple grounds, have their own requirements and we have our own regulations and expectations. So many of these laws are old, they do not fit in with the modern world and modern governance.” Karun’s solution would be to form a committee of all those organisations in the national park and start working together to reach the same goals.

“Otherwise who knows what’s going on around here?”

Utter rubbish

What with thousands upon thousands of people living on the mountains and the even larger numbers of tourists visiting every day, what happens to the garbage?

According to Karun (SDAO), in 2004 his office campaigned successfully to rid the mountains of rubbish and while temporary dumpsites are still used for a couple of days, SDAO’s garbage trucks climb the mountain twice a week to collect all of its garbage. “There is no garbage left on the mountain anymore,” he announced; a statement echoed by the Doi Suthep temple abbot, who insists that all their garbage is collected and only organic waste is allowed to be disposed of naturally.

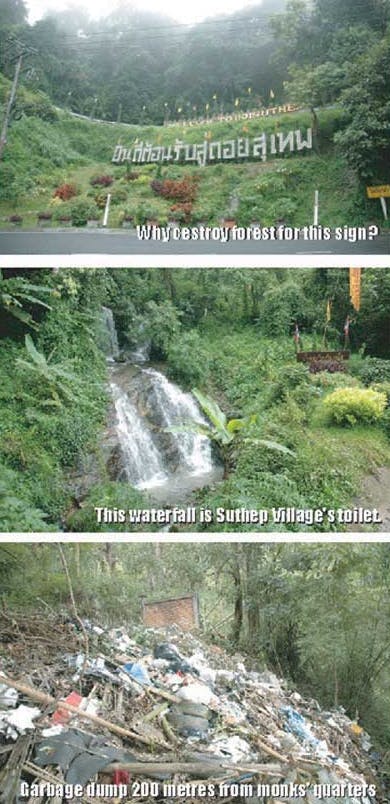

You can draw your own conclusions with the photograph (bottom) of a dump-site not 200 metres from the monks’ living quarters at the temple. Not just newly-dumped and organic waste, but old saffron robes, used toilet seats and all sorts of nasties were discovered by our photographer a mere five minutes’ walk from the sharp curve in the road before reaching the temple.

Out of the 19 listed organisations persent on the mountain, three admitted to burning and two to burying their garbage and only the Night Safari has its oun system of disposal. The rest claimed collection from the two, twice-weekly, SDAO trucks.

“Five years ago the national park decided to dig large pits 10 metres across and 5 deep to dump mountain garbage,” said Maxwell of CMU’s Biology Department. Everything went in, including heavy metals such as batteries. Who knows what will happen when these materials seep into the ground in ten to fifteen years time? There is no way to reverse the damage now, it is too late.”

what’s up with the water ?

Just think about it. Thousands of people bathing, washing and toileting every day, thousands more in the city foothills doing the same thing…where does all the water come from? According to Maxwell, the water crisis is the most frightening of all. In 1992-1993 twenty check dams were built to keep the water on the mountain. “This is not natural, especially in evergreen forests,” claimed Maxwell. “Once water is stopped, it increases sedimentation which backs up the waterway, killing trees. The water seeps down anyway – that’s gravity. These ill-conceived, inefficient and incompetent dams are causing hydrological and ecological disasters. And, with this government’s blessing, another twenty-odd check dams have been built over the past few years, earning undeserved praise and promotion for government officials.” Several formerly pristine streams in the Chang Khian Valley have now been destroyed due to the lack of an environmental impact assessment before initiating these projects.

Not only are waterways being meddled with but the mountain is literally being sucked dry. When Phuping Palace was built in the 60s the Doi Pui watershed at 1450 metres provided a reservoir for dry seasons, but over the years, this reservoir has been tapped into by all sorts of villages and organisations leading to an alarming drop in water levels. Twenty years ago a 75 metre deep aquifer reserve under the rocks – which had been there for millions of years – was penetrated by a drill which has been sucking vast quantities of water out ever since. “No one knows the full environmental impact of these activities,” said Maxwell, “but they could be disastrous.”

It hardly bears thinking about…no waterfalls, no trees, no animals and lots and lots of floods for us city folk.

“No one is in charge of the mountains’ water supplies,” said Karun of the SDAO, “my worry is the Night Safari. Think of all those animals and the water they require, then there is the Royal Flora project growing non-indigenous plants which need even more water.”

And after the water’s used ?

This is quite disturbing.

You know that pretty little waterfall by the sharp curve just before you get to the temple? The place where tourists are always seen dipping their feet into the falls, basking in the rainbow-streaked spray for a Kodak moment to cherish forever?

Well, sorry to burst you bubble, but it’s pure sewage. While the abbot of Doi Suthep temple insists that all temple waste water is treated, Sompong Paphonpat the Suthep village head, sheepishly admitted to me that he had no budget for treatment and all village (and tourist – for which the villagers cheekily charge up to five baht per flush) waste goes straight into the stream, trickling down Pa Laad waterfall (hence the recent evacuation of the Pa Laad temple as a meditation retreat), on down to my favourite sliding falls, Montatarn, then down to pool in CMU’s Angkaew reservoir over which students gaze romantically every day.

“It is the only thing that weighs on my heart,” Sompong told me with a sigh.

We called the organisations working on the mountains according to the previous table, and asked them what they did with their sewage and found that out of the 19 organistions, only the Queen Sirikit Botanic Garden, the Doi Suthep Temple and the Night Safari had waste water disposal plants. The rest just let their waste flow into nature.

“They got a forty million baht budget from this government under the SML scheme,” said superintendent Surachai disgustedly. “Instead of dealing with their waste, they built a bigger car park. They tell me to mind my own business as it is an internal matter, even though we all know that their irresponsible behaviour affects the entire national park. ”

“Bangkok has carried this country’s economy, development and growth, it can no longer carrythis country alone. Chiang Mai needs to pull in and that is why this project is important.”

Plodprasob Suraswadi, on the 12 billion baht Chiang Mai World project.

“While waste water is not necessarily bad for the environment, – it can actually be quite nourishing – excess isn’t, as algae use up oxygen which could kill life in the water. While this process is reversible, it will not happen here as there is no budget, and even less will.”

Snapshot

“While the snapshot of the national park may look good,” says Rungsrit of the Lanna Birds Club, “If you had a crystal ball and could see into the future, the prospects are grim.”

Where to start ?

It’s all rather overwhelming I must admit. But a good place to start would be to contact the ‘For Chiang Mai Group’ which is organising a mammoth event in November hoping to rope all organistions and groups involved and concerned into a comprehensive series of talks and data gathering. “The problem is that people don’t see Doi Suthep as an entire mountain range,” said Patcharin Sugunnasil coordinator for the group. “They see it as destinations – palace, temple, waterfall, etc. – and not as one ecosystem.”

“My band was asked to play a nightly gig in a planned campsite between the Night Safari and the Royal Flory Project, naturally I didn’t think that rock and roll and national park camp sites gelled, so I refused.”

Joe Cummings (Lonely Planet Thailand)

We are so lucky to have our heaving green lung on our city door step, but I think that it is time we stopped relying on government PR and start asking questions, demanding answers and then double check the answers given.

The issues I have touched on are just at the mere tip of the mountain (so to speak) and while I may have simplified them for brevity and clarity, obviously these problems are extremely complex.

But the good news is that now you know. What are you going to do about it?

If you are interested in getting involved with this issue, please contact Adrian Pieter, who is coordiating Navember’s saminar at 053 893158

“The planned cable car is making fun of something sacred and serious.”

Hans Banzinger

“Big problem with the mountain is that there are too many people playing host (chao pap).”

Karun Khalaiklueng (SDAO)