Towards the end of each winter here in the north of Thailand a silent and stealthy enemy arrives: a pall of pollution that smothers the city and its surrounds like a toxic blanket. It’s a foe that’s grown more menacing by the year, as dust and smoke have combined with other noxious gases to form a dangerous atmospheric cocktail. In 2007, smog reached such a critical level that northern Thailand made it onto BBC news, and this year, the haze has been bad enough for a visiting member of the Polish media to dub it ‘the most polluted place he’d ever been’.

The region’s smog problem is as ancient as it is complex. People have been burning forests in northern Thailand for centuries: clearing the way for farmland, smoking mosquitoes away from livestock, and scorching the land in the belief it boosts the yield of forest products. Modern life has only compounded the problem: as forests have dwindled, carbon dioxide levels have risen; industry and agriculture have mushroomed, along with pesticides and emissions; vehicles on the road have increased in tandem with traffic fumes; and the invention of plastic has added a particularly poisonous element to the burning of waste. Most of us who have lived with this perennial problem have more than rudimentary knowledge of its multi-faceted causes.

This year, pollution has once again risen to critical levels in certain parts of the country, with the level of fine-particle dust (PM10) in the atmosphere hitting 172.1 micrograms per cubic metre in Phayao and 185.5 in Lamphun on February 24th – relatively early on in the burning season. These figures are well over the national safety standard of 120 micrograms per cubic metre and almost four times the safety ceiling of 50 set by the USA, Britain and the rest of the European Union.* Translation: they pose a serious danger to wellbeing. So fine are PM10 particles that they can be absorbed into the trachea, causing irritation that can morph into bronchitis, asthma attacks or other respiratory difficulties. Even more hazardous are PM2.5 – particles so minute that they can penetrate the lung cells. If breathed in repeatedly over a long period of time, they create the potential for gene mutation that finally evolves into lung cancer.

*At last check before we went to print, the pollution index had hit a high of 437.8 micrograms per cubic metre in Mae Hong Son on 17th March, nearly four times the national safety standard and over eight times the UK limit.

The most drastic documentation of pollution-related fatalities was during the Great London Smog of December 1952, when the burning of cheap sulphurous coal produced such toxic air that 4000 more people than usual died in just five days. In the weeks that followed, 12,000 more died and 100,000 fell ill from respiratory ailments linked directly to the smog. The incident woke up the world to the dangers of haze pollution and spurred restrictions on burning coal, but recently, research into California’s poor air quality revealed that the state racks up roughly $193 million annually in smog-related hospital care. Though the health hazards of Thailand’s haze have not been well-documented, Deputy Public Health Minister Pansiri Kulnartsiri estimated pollution in the northern region had led to an eight-fold spike in respiratory ailments by late February this year. It may also be no coincidence that Chiang Mai province has the highest rate of lung cancer in the country.

Despite the haze’s health repercussions; despite a recent study that has showed forest mushrooms and vegetables to be more prolific in areas absent of fire; despite the fact that tourism to northern Thailand plummets in the mustard-coloured face of the haze, with a domino effect on the economy…despite it all, the burning continues each year. It is a way of life that has become deeply entrenched and therein lies half the problem. One northern villager commented: “It’s just our normal way of life; we have used fire for many years. It doesn’t last forever. When the rainy season comes the conditions will improve”.

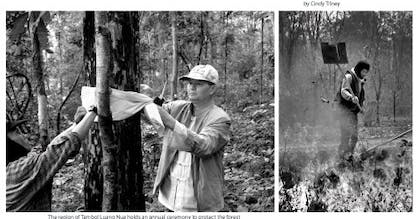

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Though the burning issue may take many more years to resolve, a handful of northern communities have finally begun to take matters into their own hands. Several villages from the region of Tambol Luang Nua, near Doi Saket, are taking a grassroots approach to the problem, with surprisingly successful results. A diverse collection of bodies and individuals – village elders, the police, fire brigade, District Administration Organisation (DAO), business owners and local residents (both Thai and foreign) – are all working together to clean up the air and conserve the environment. One of the key projects is a fire response plan formulated to deal with the annual burning crisis. Through a network of volunteer firefighters and lookouts stationed at various points, as well as funding from the Royal Project, the task force has managed to put out 40 fires in the last two months [mid March at time of writing].

But there are many obstacles involved, says nayok tessaban Duangkaew Saadluan: “Manpower is insufficient to cope with fires burning in more than one place, and fires burning high on the hills can’t be accessed by the fire engine. We have only 80,000 baht to fight fires for six months over a 75,000 rai area, but realistically our 11 volunteers can only police 1,000 rai. There is also resistance from some locals, who prefer to take the quick and easy option of clearing land by burning it rather than through hard labour. And others, who live off the land, still believe that certain edible forest plants grow better after burning, so they see it as a matter of survival.”

The Tambol Luang Nua initiative is not only one-dimensional, explains Duangkaew. “Students from Mae Jo University have visited and set up school programmes to teach the negative effects of burning so the younger generation grows up with a different outlook. We are encouraging people to compost their leaves, or to take them to Tao Garden [a health resort in Doi Saket], where they are making compost for their organic vegetable garden. People are fined if they’re caught burning their waste and we also have an annual ceremony to promote protection of the forest.” This ritual has had interesting results, he adds. Decades before, when trees were still plentiful in the area, natural streams came down from the mountains and provided water for the village. As the forests were stripped bare, these dried up, forcing the villagers to find other sources of water, but in the last few years, the jungle has started to recover and the streams begun to trickle back.

A study of two community forests in the region of Mae On illustrates just how vital involvement at a grassroots level is for conservation. Assessments of two woodland areas in Mae On – Ban Sahakhon Moo 10 and Ban Mae Pa Kang Moo 6 – were carried out in February and March 2009, with very different findings. Ban Sahakhon was a healthy ecosystem that had suffered little to no fire damage and was full of healthy tree saplings and grasses, while Ban Mae Pa Kang’s was distinctly degraded and showed signs of extensive burning. In interviewing the headmen of both villages afterwards, two major reasons for the differences became apparent.

The Ban Sahakhon Agricultural Cooperative – started by HM the King in 1981 – had given the villagers a sense of ownership over their land. Though the forest belongs in essence to the project, members can pass tracts down to their offspring, creating an incentive to protect it. The stance of authority figures also emerged as a driving force: Ban Sahakhon’s village headman was a respected and powerful leader who upheld the principles associated with a shared community forest and enforced regulations associated with burning. “Strong leadership is what is needed to prevent fire,” he said. “Encouraging people to think about the area and take responsibility for their actions and how each individual has a role to play in protecting the local environment”. On the other end of the spectrum, the pu yai baan for Ban Mae Pa Kang openly admitted the presence of fires in his area, saying, “Catching those responsible is difficult, because it is quick and easy to light a fire. Smoke indicates that a fire has been lit, but by then the person responsible has fled.”

It may take years – even decades – for northern Thailand’s burning issues to be resolved. But the willingness of the local communities to take responsibility for the land around them is a huge step in the right direction, and one that can only have positive spin-offs. Already, villages neighbouring Tambol Luang Nua are beginning to show interest in starting similar firefighting projects and at Ban Sahakhon last February, villagers went as far as to participate in a parade held to raise awareness of the problems associated with burning. With any luck, ideas and initiatives such as these will take hold and spread as fast as the wildfire that sparked them.