Thailand was dragged into the Second World War on December 8th 1941. Due to the time difference, the Japanese Navy mounted an assault on Thailand’s southern coast about the same time as they attacked Pearl Harbour on December 7th. Thai troops immediately defended the country, with battles erupting in Prachuab Khiri Khan, Chumphon, Songkhla, Pattani and Had Yai. Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram, the Prime Minister of Thailand, said before the attack that Thailand would fight to the last drop of blood. Yet, while these troops were being marched to their inevitable death, Phibunsongkram and the rest of the cabinet met in secret to discuss their surrender. In just 12 hours, and with hundreds of Thai and Japanese soldiers dead on the beaches, Thailand had declared a ceasefire, giving Japan free passage throughout the country on condition that, on paper at least, Thai sovereignty and independence were safeguarded. Until this point Thailand had tried to remain neutral in the growing global war but with the ceasefire agreement set in stone, Thailand had sided with the Japanese. Just one hour after that decision however, Phibunsongkram received a message from Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, which read “There is a possibility of imminent Japanese invasion of your country. If you are attacked, defend yourselves. The preservation of the true independence and sovereignty of Thailand is a British interest, and we shall regard an attack on you as an attack upon ourselves.”

Chiang Mai was not exempt from the war. With the invasion of Burma on the horizon, Chiang Mai and other northern cities were commandeered by the Japanese to help their war effort. Soon the Shan States were seized and then given to Thailand by the Japanese who wanted to keep on good terms with their somewhat unwilling hosts. Thirteen days after the invasion, on December 21st, Thailand concluded a military pact with Japan and established the Payap Army, a troop of 70,000 army and air force personnel that were assembled in Lampang, the city which would serve as the headquarters of the Japanese Army and Air Force throughout the war. Convinced that Japan was going to win, Phibunsongkhram declared war on the Allies via telegrams to the United States and the United Kingdom. The Thai ambassador in Washington, D.C. at the time publicly repudiated the declaration, refusing to deliver the message to Franklin Roosevelt, the US President, whereas Churchill received the message loud and clear, and to this day Thailand is the last country that Britain has officially declared war on.

Thailand was on the side of the Axis, but debate still rages about whether Thailand was forced to declare war on the allies or not.

The United States considers Thailand’s status during the war as an occupied country, unlike the United Kingdom. This is due in part to the Thai ambassador’s stance but also to Pridi Banomyong, the then finance minister and future Regent, who returned home at the start of the war and immediately started the underground Free Thai Movement (Seri Thai). Seri Thai soon brought together a number of other key figures such as Jamgad Palangkoon (the first envoy who smuggled the first Seri Thai message to the outside world), Prince Bhisatej Rajani, head of the Royal Projects, Puey Ungpakorn, the Thai Student Union leader in England and Prince Subhasvasti Svasti, a member of the royal family who followed King Prajadipok into exile in 1933. Working underground, the Seri Thai Movement spent years galvanising locals from across the country in training to prepare to attack the Japanese when the time came. Ironically, just days before they were ready to strike the Japanese occupiers, the Asia-Pacific war came to an abrupt end following the dropping of two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

History books around the world recount stories from the 415 kilometre Death Railway in Kanchanburi. Built by around 60,000 allied prisoners of war, and an estimated (and little talked about) 270,000 civilian labourers from Thailand, Malaya, Burma and the Dutch East Indies, this is unanimously understood to be the most tragic chapter during the war in Thailand and the only chapter known in popular history. However, Northern Thailand played a key role in the Japanese offensive during their movement into Burma, our city acting as a main headquarters and eventually becoming the graveyard for hundreds and thousands of fleeing Japanese soldiers after the counter offensive by the British army. This story is little known and much has been lost to memories and jungles.

The Tigers Look South

Compared to the rest of East Asia, Thailand remained relatively peaceful despite being home to Japan’s main headquarters during their offensive on the region and very few battles were fought in the north of Thailand. The Allied Campaign against Thailand during the war was almost entirely aerial, due to the challenges of the mountainous region to the north and west of Thailand. In the wake of the Sino-Japanese War where over two thirds of China was under Japanese occupation by 1940, Roosevelt agreed to provide secret air support to China. The American Volunteer Group, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed in China and was ordered to defend China and the Burma Road. Following the invasion of Thailand and then Burma by the Japanese, the Flying Tigers had their eyes squarely on the region.

Towards the end of March 1942, the Allied air force was pushed out of Burma after a successful attack by the Japanese.

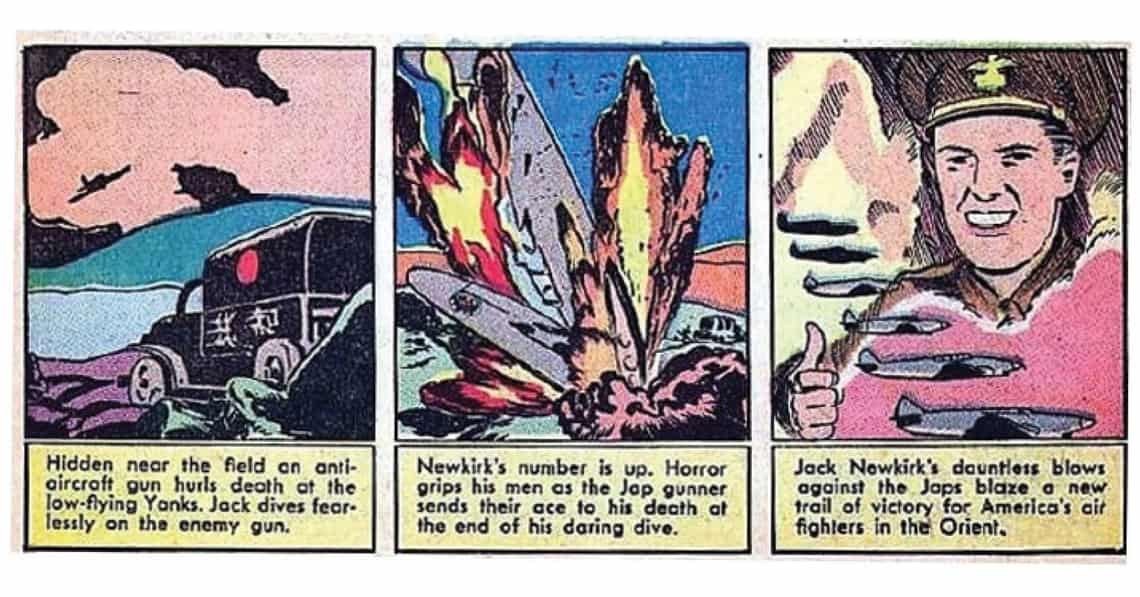

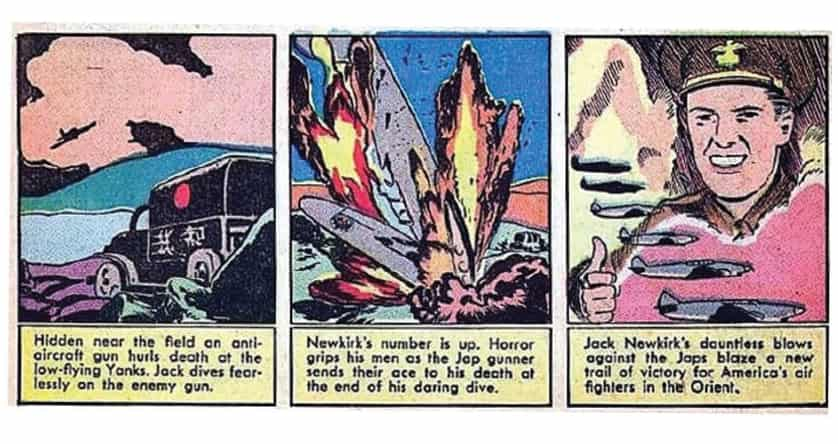

The Americans fled to China to regroup with the Flying Tigers and the British RAF fled to India. The commander of the Flying Tigers, Col. Claire Lee Chennault, ordered a revenge raid on airfields in Chiang Mai and Lampang, places he suspected were being used by the Japanese war machine. Two squadrons of P-40 Tomahawks, with their iconic shark teeth decals on the nose, made an attack on Northern Thailand on March 24th. One squadron was tasked with attacking the Chiang Mai Airfield, and after a successful attack one pilot, ‘Black Mac’ McGarry, was hit by ground fire and crashed into the jungle in Mae Hong Son. He survived the crash but was then quickly taken prisoner by the Thai police before being imprisoned in Bangkok until he was set free by the Seri Thai Movement in 1944.

The second squadron was bound for Lampang, and if they had made it that far, the entire war in the region could have been very different. At this time the Allied forces were still unaware that Lampang was home to the main Japanese headquarters in Thailand, and returned home with no idea as to what lay over the mountain range. It is believed that they mistook Lamphun for Lampang, and upon seeing no troop movements, headed back. When they turned around they followed the railway back to Chiang Mai but were intercepted by gunfire coming from the Ban Tha Lo railway bridge over the Mae Kuang River. Circling around for a dive attack, Squadron Leader Jack Newkirk saw what he thought was an armoured car on the road and attacked. As he dove his wing hit a tree and he crashed into a rice field ahead. The armoured car turned out to be an oxcart and the driver was killed by the gunfire. Locals buried the pilot’s remains in the rice field, in a western grave next to Wat Phra Yuen. They were returned home after the war but memorials are still held at the temple from time to time. To this day, remains of the downed plane in Lamphun can be still be seen at the Tango Squadron Museum found in the Wing 41 Airbase at the Chiang Mai International Airport along with the wreckage of ‘Black Mac’ McGarry’s P-40 that was found by villagers in 1991.

Temple Prisons

Prisoners of war were quite rare in the north, with most who were captured during the Burmese offensive either kept in Burma or sent to Bangkok and Kanchanburi just like ‘Black Mac’ McGarry. However, while occupying Chiang Mai,

the Japanese used Wat Muen San, just off Wua Lai Road, as a military hospital and allied POW compound, which, according to documents written at the time was home to just 46 POWs.

It also served as a banknote printing press, printing occupation currency for Burma. Chiang Mai Railway Station was used to transport goods, weapons and personnel in and out of the north and when Allied POWs were brought in, a local mechanic and driver who happened to be quite good at English was conscripted by the Japanese to work as a translator. The mechanic soon discovered that many of the POWs were malnourished and suffering or had died from malaria. After working up a relationship with the Japanese, he began sending his 12 year old son, Orachun Tanapong, to Wat Muen San to make deliveries to the Japanese so that he could smuggle goods to the POWs held there. Food, tools and cigarettes were smuggled in by the brave young boy. In fact, Orachun was the first person to tell the POWs that the war had ended in 1945, having heard the news even before the Japanese guards. Orachun grew up to join Thailand’s diplomatic corps before taking the roll of Acting Director-General of ASEAN in the 1980s.

Wat Muan San is now home to a somewhat dusty Japanese war memorial museum built in 1981, housing several artefacts and documents from the era. There are statues of Japanese soldiers alongside Buddha statues around the temple and outside the museum is a plaque with the words ‘May Peace Prevail on Earth’ written in three languages; English, Thai and Japanese. It is also alleged that many Japanese soldiers were buried on the grounds of the temple as they didn’t have the resources to cremate all the corpses. Today, annual memorial services are held at the museum on August 15th, in honour of the date of the end of the Asia-Pacific War. This year’s event will auspiciously mark the 72nd year, or 6th cycle, since 1945.

Northern Scars

Signs of Japanese occupation can still be seen in Northern Thailand today. Numerous roads, airstrips and temples were built or used by the Japanese army. Present day Highway 1095 that stretches from Chiang Mai to Mae Hong Son is one of those scars, having been built as a dirt track to the border by the Japanese. Although reaching northwards, the Japanese looped the road to join with the city of Mae Hong Son before cutting a small road across the border heading westward out of Khum Yuam. The last stretch of this road was never finished before the end of the war, but during its construction many locals died from the terrible conditions after being used as slave labour.

The road had been intended to be used for logistical support but also helped supply the Japanese troops during their failed Imphal Campaign into Northeast British India. However, the success of the British saw a disorganised retreat by the Japanese across Burma that finally flowed into Northern Thailand. Highway 1095 soon became the main escape route for the thousands of Japanese troops who were all but abandoned by their commanding officers and who had to find their own way back into safe Japanese territory. It was eventually dubbed ‘Skeleton Road’ by the Japanese as it was littered with bodies of fallen Japanese soldiers who had died from war wounds, malaria or exhaustion.

In addition to the disorganised retreat, Karen and Karenni guerrillas appeared out of the jungles along the road and attacked the already severely diminished soldiers. These guerrillas were armed by the British after they sought help in retaliation against the Japanese for drafting hundreds of tribes’ people into forced labour.

An estimated 12,500 Japanese troops were killed by the tribal guerrillas as they retreated into Thailand along that one road alone.

Although almost all who survived managed to regroup with the Japanese army and return home after the war, a few decided to stay. One of these men was Fujita Matsuyoshi who was eventually naturalised, and spent his life, until his recent death, dedicated to collecting the remains of soldiers who died along the Skeleton Road. The remains of approximately 100 soldiers were sent to Japan in the 1980s after decades of work by Matsuyoshi, who also erected a memorial from his own funds in Ban Nakhon Chedi, Lamphun.

Still Standing

Despite the lack of attention given to this important chapter in history by the Thai government — mostly due to a series of political catastrophes following the war which saw the Seri Thai resistance vilified then forgotten following Pridi’s exile, and also for being on the losing side — memorial sites do exist, with most being Japanese rather than Thai or Allied.

In addition to the places mentioned already, you can still visit a number of locations which are either relics from the war or memorials of remembrance. The Ban Tha Lo railway bridge in Lamphun is still there to this day and the San Khayom railway bridge just down the road is perhaps the only structure remaining in Northern Thailand that still displays damage from air attacks during World War Two. Between Lamphun and Chiang Mai sits the Ban Kat Technical College which is now home to a Japanese memorial site built in 1995 after the bones of thousands of Japanese were discovered. In town, the museum at Wat Meun San is accessible if you can find a monk with a key, and you can visit Wing 41 Tango Squadron Museum, though you are supposed to write them a letter requesting permission first. The Chiang Mai Foreign Cemetery hosts a memorial service every Remembrance Day on November 11th, and is also home to a black obelisk honouring the Flying Tigers, as well as being the resting place for several foreign war veterans who made Thailand their home after the war. Along Highway 1095 is the largest Japanese war memorial in Northern Thailand located in the grounds of Wat San Kayoum in Ban Kat village. Two Japanese hospital units also buried the dead in Don Kaew, just north of Chiang Mai, but sadly, to this day, neither camps nor graves are marked despite the estimated body count of over 400. However, all bodies exhumed were flown back to Japan following efforts by a war veteran group under the motto “Leave not one body behind”. Slightly further afield in Mae Hong Son, there is a private World War Two museum full of Japanese and Thai artefacts from the war, collected by Police Lt. Col. Cherdchai Chomtavat during his time working as a police officer in the area. If you go straight to the border, a police blockhouse built in 1901 that was used by the Japanese during their retreat into Thailand on the banks of the Thanlyin River and can be found, still standing, near the Tha Ta Fang School in Mae Yuam.

Citylife would like to thank historian Jack Eisner, M.R. Saisvasdi Svasti (daughter of Prince Subhasvasti Svasti), Major Roy Hudson (World War Two Veteran and one of the longest living foreign residents in Thailand, first moving here 77 years ago) and www.lanna-ww2.com for their time, images and detailed descriptions of what happened during the Second World War in Thailand that helped make this article possible.