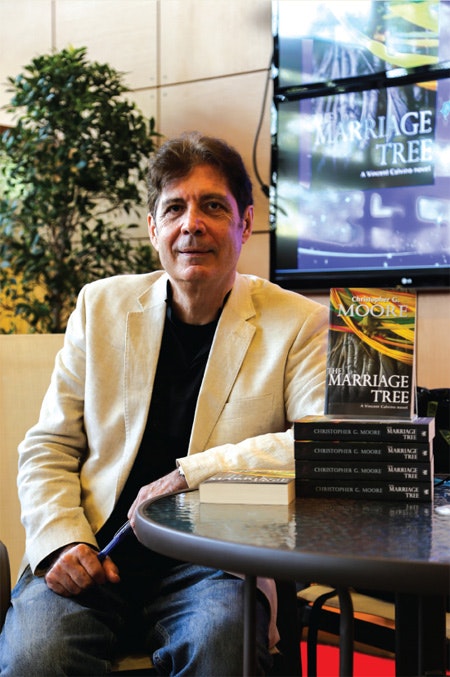

When you talk with Christopher G. Moore about his new book, The Marriage Tree, the 14th in the popular Vincent Calvino detective series, it’s not long before he is focusing on the broader themes that are present in all of his books, the role of the novelist as social commentator, and the challenges created by an ever-changing world. Sure, you learn about the book, but, in the end, you learn more about the man.

For avid readers and fans of the noir crime genre, Moore and his fictional Bangkok private eye hardly need an introduction. His books have been translated into 14 languages and received critical acclaim and awards from around the world. With his latest release, this Canadian law professor turned novelist has put together a contemporary story examining recent events in Thailand and the contribution of technology to the current state of humanity, all within the context of an unsolved murder.

Moore describes The Marriage Tree as “a book that looks at how technology has made it almost impossible to be a missing person anymore. The old necessity of a paper chase and talking to people has been replaced with a digital world where it is much easier to track people. It is also the story of people living under the radar, illegal immigrants, and what happens to a displaced people, like the Rohingya, when they end up having no resources, no friends, no kind of political power, and they are put in camps where they are vulnerable to the temptations of exploitation. The Marriage Tree is about people who set up an underground organisation to help extract Rohingya and other illegals who are being exploited.”

The topics of Moore’s books are always timely and ethically motivated. The plight of the Rohingya had been in the news and fit right into his pattern of writing. “What I try to do is to keep the novel as a chronicle of our times, particularly in Thailand and Southeast Asia,” he explains. “People who can take care of themselves, you don’t really need to write about them; they have their own ways to cope with the rough edges of life. But the Rohingya is a very vulnerable group.”

In putting the Rohingya’s story within his own, Moore looks for a way this issue, and others, will remain with the reader long after the book has been read.

“The news of things comes and goes,” he observes. “What seems absolutely significant on the front page today, two weeks from now people will vaguely remember. What a novelist does is try to put them in a larger context. At that point there is a chance that a book will be meaningful this year, next year, and the year after because the issues are universal and, through the novel, have specific individual cultural expressions.”

Through Vincent Calvino, Moore writes from the perspective of an expat living in Bangkok. After 25 years of living in the city and being a keen observer of the world around him, Moore himself is somewhat of an authority on the subject. As a result, he’s become known for his ability to give the foreigner insight into Thai culture and to put expat life into clear focus. The fact that he is fluent in Thai just adds to his credibility.

“The value that a writer should bring to a book is to be able to give the wide angle view, to the extent that you can pull the lens back, talk about the local beliefs and culture and rituals and somehow put it in a larger universal context,” says Moore.

In the case of The Marriage Tree, insight into Thai culture starts with the title, which was inspired by Moore’s visit to a friend in Chonburi. Near his home, the friend pointed out a so-called “marriage tree” which he said contained the spirit of a 1950s Thai rock star. If a young woman dies before she is married, he explained, her family buys a wedding dress, has a ceremony with monks, and that dress is hung from the tree to signify that the young woman is now married to the spirit. For Moore, this was the spark.

In the novel that grew out of that spark, Moore says he is “looking at Thai culture as encompassing the language and the politics of the place. It’s an insight into the mindset of two communities, how foreigners view events that go on here and how Thais view events, particularly, traditionally powerful Thais. It looks at what are the limits on power, what are the restraints on authority, and if there aren’t any, what does that mean in terms of how people live their lives?”

There are a fair amount of Thai words and expressions in Moore’s Calvino books and The Marriage Tree is no exception. However, there is one word that stands out among all the others: jai. The word translates to “heart” but it goes far beyond that. Much like the Eskimos have hundreds of words for snow, the compound forms of jai (900 and counting) hold a similar position in the Thai language.

Moore believes comprehension of the jai expressions is a porthole into Thai culture and the changes it is undergoing. “Kreng jai is a good example,” notes Moore. “A little bit of awe and fear: it’s essential to the whole patronage system, the whole system of obedience, to respect authority without question. What we are seeing now in Thailand is an erosion of the whole kreng jai system. And once you erode a crucial cornerstone of a culture, it’s going to have political, economic and social ramifications.”

Just as Thai culture evolves, so does Bangkok, its expat community and its criminals. The world that Calvino entered in 1992 is basically gone. The once-centralised figure of the sleazy expat, focused on the sex-driven back soi, is today on the far fringes of the expat community. The Marriage Tree reflects a Bangkok with a wealthy international farang lawyer in a high-rise office, an intellectual NGO worker, and a yoga master functioning as a guru. Even Calvino, who used to eke out a living, is now settled comfortably in a condo overlooking Lake Ratchada.

Despite all of these changes, things can still go terribly wrong and usually do, and because of this the noir aspect of the series is alive and well. “The criminals are changing and the opportunities that they have are slightly different,” notes Moore. “The ways of getting caught or exposed are different, but the nature of crime has not changed that much. Noir is a reality that we can’t really ignore.”

Moore jokes that the 25 novels he has written over the last 30 years are really just one novel with 25 very long chapters. A generation’s worth of political, economic, and social evolution is chronicled, and all transformed through globalisation and technology and the movement of people. It is within these changes he finds the friction points, the points that give rise to the plot of each novel. And right now, he points out, we are in a period of very rapid transformation.

“Rapid change causes dislocation, psychological problems, and people reacting emotionally,” he says. “You either adjust and adapt or you find ways to be reactionary, and that’s a lot of what’s happening politically in many places.

Our institutions, our morality, the politics: they no longer have the luxury of time to slowly adapt to the changes as they come along. Suddenly that pace has increased to the point where adaptation is very difficult. Large institutions are like supertankers; you can’t turn them around like a speedboat. But we live now in a world where you need to be able to navigate as if you are driving a speedboat. That’s hard to do without sinking your ship.”

The frictions these situations create are interesting to Moore because, as he says, “a novel is really about emotions, not events. It’s about the way people react emotionally to change, how they act morally, and whether they act responsible or exploitive given a particular temptation that’s in front of them. Temptation created by, for example, globalisation; in some ways it has allowed more efficient means of exploitation, not just of resources, but of people. This has increased the temptation to exploit and as a result we lose more of our humanity.”

Although Moore has perfected the use of the novel as a vehicle for social commentary, he has also found an additional outlet to satisfy his passions. In July of 2009, he started a blog and invited a group of international writers who write about different cultures to contribute a weekly essay. He is of the opinion that those who are fluent in language and narrative and are observers of human life ought to be looking at things outside of fiction as well, examining aspects of the economy, of culture and politics.

Another focus of the blog is to examine authenticity as a part of fiction. Moore explains, “We have a higher expectation from fiction being truthful than reality being truthful. Reality is riddled full of all kinds of inconsistencies, but fiction has to somehow be plausible. Plausibility and truth are things that have to be separated out. The blog allows a format for doing this. A lot of the nonfiction blog is kind of the intellectual foundation, or infrastructure, for the fiction itself. The story in a novel is more about our emotional calibration, while in the blog, you’re looking at things from a less emotional, more intellectual point of view.”

Free from the burden of creating a plot and characters, Moore posts his own essay every Friday at 9 a.m. where it stays until 9 a.m. on Monday, when it’s changed to someone else’s essay. During that time he receives between 25,000 and 30,000 hits.

While free from the burdens of a novel, his weekly blog does not come without frustrations of its own. “Everyone was born to write an op-ed,” Moore says. “Two of them. The third one becomes a little more difficult, the fourth one they’re pacing up and down, the fifth one they’re standing on their balcony and wondering whether they should jump now or later. It’s living under a kind of tyranny, self-imposed, an intellectual journey, where you must now put your mind to what you are going to write about this week and not make a total fool of yourself. ”

So when will he write the next Vincent Calvino novel? Moore has some choice words on that topic: “Whenever I finish a book I always say, ‘That’s it! Put a gun to my head, pull the trigger, but I’m not going to write another book!’ And I’ve been doing that since 1985.”

He laughs. “Do I really want to go through this process again? I’ve done over 30 books; it’s like going through 30 messy divorces. They are exhausting. You’re living through all of these characters and you’re watching them evolve throughout the story. When you finish, you’re like, whoa, let me out of this. I don’t want to do this anymore. People think it’s an easy thing, but it’s a hard thing to do.”

In other words, the next Vincent Calvino case is expected to hit bookstores sometime in late 2014.

Christopher G. Moore’s blog can be found at www.cgmoore.com/blog