All in a Day’s Work

Songsri ‘Oy’ Ruankaew is a busy but contented lady. At 39, she has a fledging business, multiple places of work, an adopted 12-year-old son, a car, a motorbike, and best of all, no debt.

Life never handed her any of these things. Born to one of the poorest farming families in a farming village in Mae Rim, Oy learnt early in life that if she wanted something, it was up to her to go and get it. While her family could afford the bare necessities such as food, Oy had to sell vegetables in the market from a young age to pay for ‘extras’ such as shoes. She left school at 12, knowing that she had to help her parents work in order to send her younger sister to further education, so she took free courses at the Non-Formal Education Centre in sewing while completing high school through correspondence courses.

Eventually, Oy got a job at Green Valley as a caddy earning 50 baht a day. Realising that this was not going to take her where she wanted to go in life, she joined a Thai massage course, negotiating to pay the 3,000 baht fee in small installments. She eventually landed a job at a massage shop in Kad Suan Kaew and, sharing a flat with many other women, scrimped and saved enough to send her sister to Mae Jo University, from where she graduated. With one responsibility completed, Oy realised that her parents were getting old, and that she needed to earn still more to secure their retirement.

It was then, ten years ago, that she was hired by a retired American couple to massage them at their condo. “The first time Oy came to us, she brought a friend with her who waited downstairs and was told to call the police in one hour if Oy didn’t return,” said the American lady, who is still receiving daily massages from Oy a decade on.

“It was my first time in an elevator,” grinned Oy, who now speaks English after years of interaction with the American couple and their friends. Taking on more and more work, she eventually became the cleaning lady as well as doing the laundry for this couple, along with seven other foreigners living in the same condo.

“The Lord Buddha gives us all 24 hours a day. It is what we do with it that makes the difference,” said Oy, who starts her day at 5 a.m., dumping a load of laundry in the machine before going to the market and returning to cook for her now aged parents. She then heads off to the condo to work for her expat clients before returning home to prepare lunch for her parents around noon.

Due to her work ethics, Oy has now also become the accountant for her village’s one million baht fund – for this she is paid 150 baht a day. Oy pays the utilities for her village, sets money aside for eventualities such as funerals, and sits on the 15-person committee to dole out loans to those who need it. Following the government initiative, she is also on the committee to help restructure non-formal loans, helping those who are paying up to 20 percent interest to loan sharks start afresh with low interest loans of one percent. Her system has been so successful that in May she was visited by Minister Warathep Rattanakorn, who uses her as a case study for the programme’s success.

As if that weren’t enough, Oy also helps out her fellow villagers with personal loans when they wish to purchase something on time payment, helping them to buy a refrigerator or motorbike while adding a reasonable five percent interest rate. “So far, in all my personal and the village’s loans, we have had everyone pay back,” she says proudly.

When she finds time she earns extra money on Sundays by helping a friend at her coffee shop and recently she started up a modest sticker and sign printing business with another friend, which is slowly beginning to yield dividends.

Today, Oy is highly respected in her village and can hold her head up high as a contributing member of society. She lives with her parents and adopted son (the son of a cousin who passed away) in a household that boasts a car, a motorbike, a bicycle and all the mod cons she ever only dreamed about as a child. Some months she earns up to 30,000 baht through her various jobs and ventures.

“I enjoy it, it is so much fun,” she told me. “I don’t get stressed out; I love my work. I feel a sense of accomplishment and I occasionally treat myself to a nice dinner followed by a visit to the cinema.”

Oy’s American benefactors have become like family to her, and have even taken her on holiday to Vietnam, Singapore and Bali, though they were very frustrated when Oy was denied an Australian visa.

Not about to sit on her laurels, Oy is pragmatic. “One day she [the American lady who is now a widow] may return home and I will need to build my own security,” she said. “I am now saving up money so that I can eventually own my own business. I want to open a coffee shop.”

The Long Walk to Success

Somsak ‘Ton’ Lirungrueangkit was born into abject monetary poverty. His Akha village was a good 50-60 kilometres from the town of Phrao and his family subsisted by tilling the land, tending to their cattle and, once a month, walking the distance to Phrao to sell their forest goods. Those were the only times they had actual cash. “Our village had no road, no electricity, nothing, but we lived off nature, and it was enough,” he said.

At nine, Ton, along with many other boys from the mountains, was sent to a temple for education. He arrived at Wat Srisoda where he spent four years, before moving to a temple school in Chiang Rai where he was given free education, but had to pay for food. For 50 baht a day he worked the fields and made enough to live on. He left school at 15 and joined his sister, who was working as a cleaner in Chiang Mai.

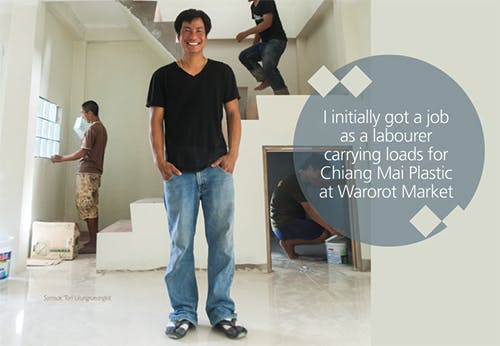

“I initially got a job as a labourer carrying loads for Chiang Mai Plastic at Warorot Market,” said Ton, now a handsome and successful 31-year-old. “I was in my late teens and knew that I needed a better education to get further in life, so I saved up as much as I could and paid the 1,000 baht a term to send myself through night school from where I eventually graduated.”

After graduation, Ton lucked out and landed a job at the real estate agency Domiduca. While his job was still menial, and he was earning only 6,000 baht per month, driving around on a motorbike all day searching for properties for rent and sale, he began to make contacts with clients and soon was taking on more responsibilities. One day a condo owner contacted Domiduca with a request to renovate his condo to prepare it for sale. Ton, who is quite a strapping young man, offered to help with the heavy work and as more work was required, he coordinated friends from his village to come in and help out as well. Soon he was working with the contractor, sourcing and managing electricians, parquet floor layers and plumbers.

Unfortunately, Domiduca closed down and Ton was out of a job. Fortunately, a few clients still had his number and would sometimes call to ask him for help here and there. Ton slowly built up his freelance reputation and has since renovated over 30 condo units, with some jobs valued in the millions of baht.

“I feel independent,” said Ton as we flicked through photos of condos he renovated on his iPad. “I feel as though I am not just a poor hill tribe boy that is looked down on anymore. I am a contributing member of society. I can send home money to support my parents and five siblings. I have a solid client base and, importantly, I have no debt.”

Ton is now the proud owner of a Fortuna and four and a half rai of land in Doi Saket, where he and his Akha girlfriend hope to someday build a house.

“Sure, I am young. I like going out and having dinner or a few drinks with friends,” said Ton, “but I don’t do drugs, gamble or drink to excess. I know that my future is in my hands and I know that I have to work hard for it. All I aim for now is to have security for myself and my family.” His average income now sits at between 40-50,000 baht a month, not bad for a mountain boy who hardly ever saw cash growing up.

True Grit with a Sprinkle of Glitter

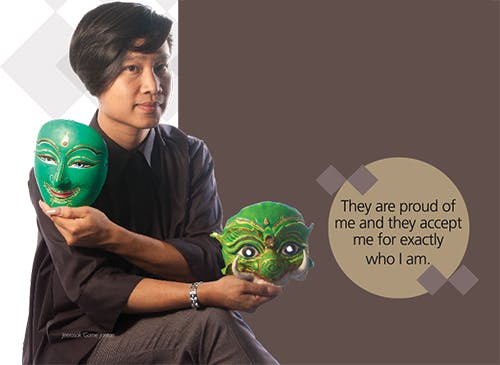

At 33, Jeerasak ‘Game’ Jantan has the face of a teenager. His effeminate mannerisms, long fingernails and trendy hairstyle add to his air of youth. But Game is no wilting lily; he understands hard work and true grit.

“My parents were from a rural village in Mae Orn where people like me, girls, are not accepted,” he told me. “I used to be beaten up for being different and my parents were always ashamed of me. All through my childhood at the village school, I was always the one involved with cultural activities – organising parades, being head cheerleader, planning cultural events like teachers’ day. But in spite of all this, my parents, who own a small village shop, instilled in me rural traditions. I was expected to become a civil servant, an accountant or a teacher, and that was their ambition for me.”

Game’s parents saved up enough to send him to a vocational school in Chiang Mai where he studied accounting. The responsibility on his shoulders was to become the first member of the family who was released from the cycle of genteel rural poverty, to gain an education and land a secure job with a pension. With the help of student loans, and after-school work such as being a waiter at the Riverside, he eventually received a degree in accounting from Far Eastern University.

“My world was small,” Game recalled of those days. “All I wanted was to be an office worker and when I was offered a teaching job at my old school, I decided to cut off my hair, become a man, and start work.”

But through all the years, starting from his university days, Game loved costumes. He would go to every cultural event he could find: flower festivals, Loy Krathong, anything that inspired him. Soon, friends were borrowing his costumes or asking him to custom-make them a cheerleading uniform or a New Year’s Eve outfit. Game realised that since borrowed clothes had to be laundered and sometimes fixed, he may as well start charging money for it. “Each time I rented out a costume, I would make a small profit and use it to make new pieces.”

Soon, Game realised that he had a huge collection of Lanna costumes and fancy ensembles, and after three years of being a teacher, he decided it was time to focus on doing the kind of work that he loved full time. With dread, he returned to his parents and tried to explain to them that he was different but that being different was not only valid, but potentially a path to greater success. Fortunately, his parents agreed to support his decision and the rest is history.

Today, Game has two costume rental shops in four townhouses, one of which he has already paid for and owns. He has also purchased a 300,000 baht godown where he houses his three thousand costumes. He supplies these items to all the events companies in Chiang Mai, to schools, to businesses and to walk-in clients. Not only that, he is branching out into events organising, having won and executed a 2,000-man show recently at the 700 Year Stadium. On a good month, Game can earn between 50-100,000 baht and he employs eight staff.

But his greatest achievement, according to him, is in the fact that his parents have not only come to terms with who he is, but are tremendously proud of him. His certificates and awards adorn his parents’ walls, and his success is now one of the crowning achievements of his village.

“My parents can hold their heads up high,” he said with a smile. “They are proud of me and they accept me for exactly who I am.”