She arrived incognito at the place she calls “the lake of liquid crystal and infinite wisdom”: “I wanted to have my own experience there, a pure, individual experience, and so I didn’t admit I was a shaman at first; I went disguised as a student,” explains Diana. “I have no words to describe the beauty. It was the first time in three quarters of a century that the borders were open, and shaman who had fled to Mongolia during the Soviet purges could return to this sacred place – all these shaman coming together to kiss the earth.”

But within two days, Diana was recognised as kin by her fellow healers, and chosen as one of 13 people to be initiated by a revered Mongolian medicine man. “If you are a true shaman, you will be recognised by your kind anywhere in the world,” she says. The true nature of this small, strong and well-groomed woman may have been clear to her peers at Lake Baikal, but to the untrained eye, she appears surprisingly conventional. The only outward sign of her profession is a pair of piercing green eyes that hold the gaze steadily and seem to penetrate through to the soul.

Shamanism has been around for aeons: it is thought to pre-date all forms of organised religion, and to have originated around the end of the Stone Age (roughly 9500 BCE). The term, meaning ‘he or she who knows’, was drawn from the language of the Evenki, a division of the Siberian Tungus people, who were devout followers of a shamanistic religion before they were persecuted for their beliefs and practices during the Soviet takeover. In fact, traditional healers have been victimised in scores of societies throughout the ages: during the spread of Christianity and the Catholic Inquisition; the Spanish occupancy of the Caribbean and South and Central America; the Great Terror of Stalinist Russia. Today, shamanism is practiced mainly by ethnic groups who have had limited access to the western world and retained their traditional customs and beliefs, though some, like Diana, are exceptions to this rule.

Born in Moscow, Diana first realised she was different from others at the age of eight or nine, when she recovered spontaneously from endocarditis and rheumatism after being bed-ridden for more than six months. Since then she has spent years studying and practicing meditation, Buddhism and shamanism all over the globe, and working with countless people in spiritual, emotional and physical need, from the Russian prime minister and Thai monks, to Nepalese orphans, Hmong villagers and Tibetan Lamas. Today, she is based in Chiang Mai, but still travels widely to teach, heal and study in different parts of the world.

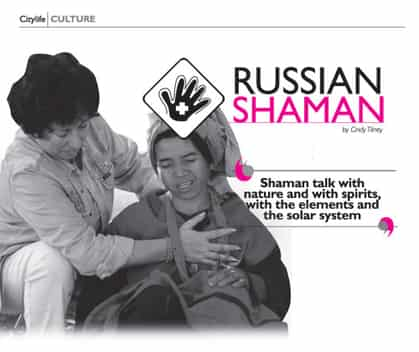

“Some people think shamanism is only philosophy, or only medicine, but for me it is a style of life,” she explains. “Shaman talk with nature and with spirits, with the elements and the solar system. We are all part of nature, we are all connected to all things – the shamanic world is not on a mountain peak somewhere out of our reach, it is all around us. But many people aren’t in touch with this connection; it’s like they cut off part of their existence; they cut off their connection to God – and God is Love, Wisdom and Truth. To feel this connection – with nature, your ancestors, your soul, trees, flowers, the sun, moon, stars – you need to give time to your soul. That is the first step, and the first problem, because people are conditioned to the ‘must’ – must make money, must do business, must have children – so they need to be reprogrammed to do rather what they like or love.”

Shaman are often referred to as diviners, traditional healers, or medicine men and women, but there’s no clear cut definition of the phenomenon, largely because the practice transcends cultures and nationalities. Such Healers can be found across the planet, from Africa to Asia, Siberia to South America. There are differences in style and approach, but all shaman share the ability to communicate with the spirit world and to promote healing and well-being (or in cases of shaman working with ‘black magic’, malaise). The tools and techniques used to commune with the spirit world vary widely, from drumming, meditation, mantras, singing and dancing, to the use of psychoactive and ameliorative plants. Diana is a Buddhist shaman, which means she makes no animal sacrifices, practices meditation, and works only with ‘white’ or good magic. “The tools I use depend on the area in which I am working,” she says, “whether it’s a healing ceremony or ritual work, removing a curse or connecting with ancestors.”

In the last 15 years, Diana has travelled 60 countries spreading her healing far and wide. “Sometimes I feel tired,” she says matter-of-factly, “but this is my work, this is what I do. If there is a chance that I can help people, if they are ready to ask ‘who am I?’, if they are ready to wake up and be truly conscious, it is enough reason for me to carry on.”