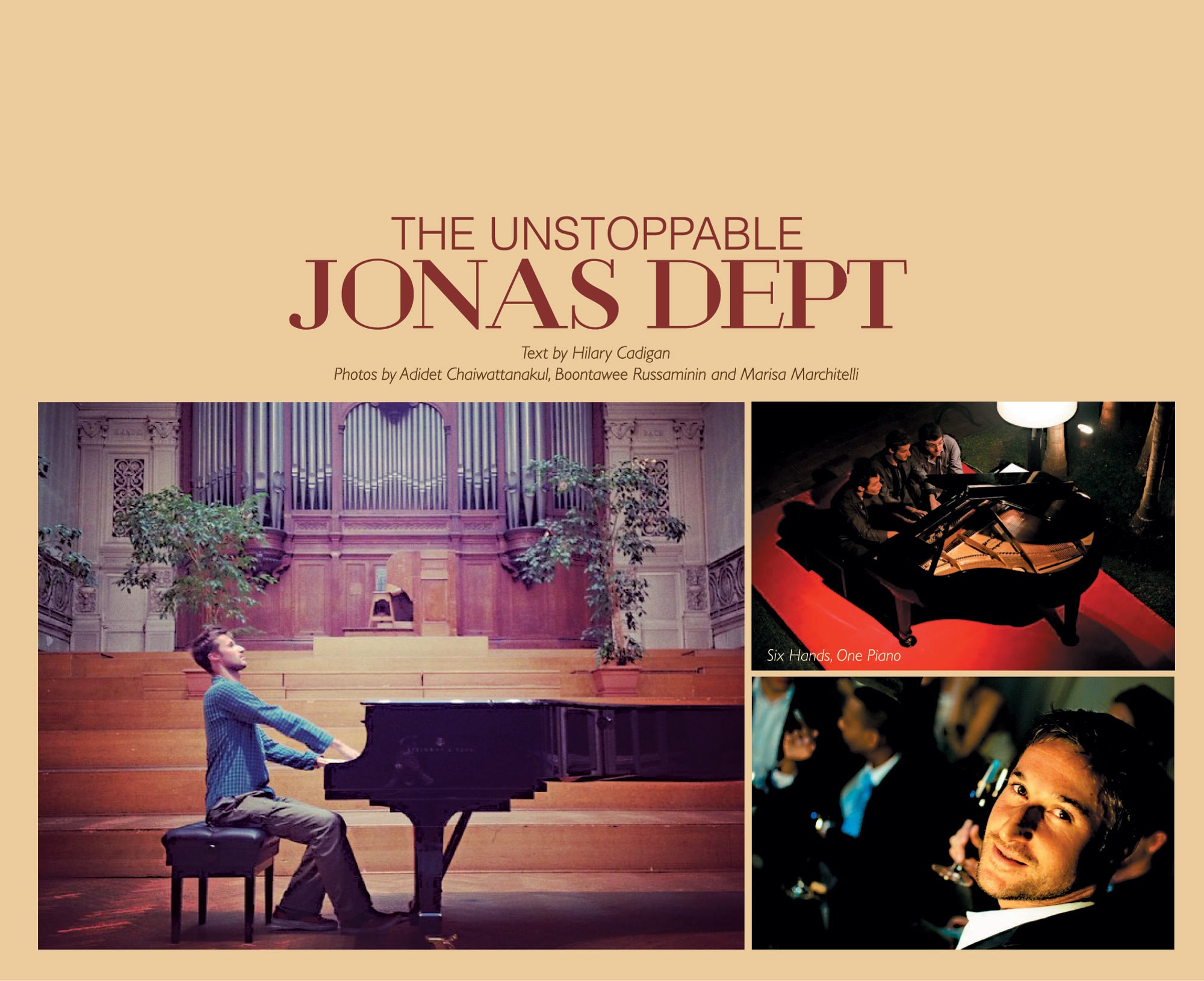

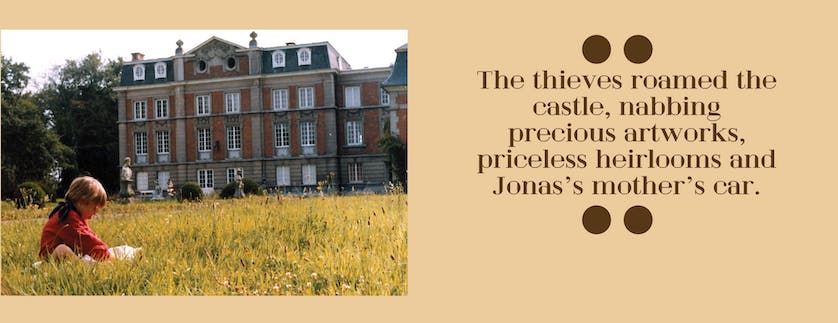

Jonas Dept sits in front of the gleaming grand piano, face calm, torso swaying slightly, fingers flying rapidly over the keys in a dance that seems effortless. Beside him sit his two co-players, their six hands moving in intricate patterns that somehow never collide. They occasionally make eye contact, smile briefly, one hand shooting out to turn the page of the sheet music before returning to the ivory, barely breaking stride.

The “Six Hands, One Piano” act has become a bit of a trademark for Jonas, who now plays regularly in Chiang Mai with two old friends from his Royal Conservatory of Brussels days.

“Six hand piano playing was very uncommon when we started,” Jonas tells me, taking a drag from his cigarette. We’re sitting at a small bar in Chiang Mai, sipping beer from frozen mugs. “I started doing it because I happened to have a friend who was a pianist visiting me here in Chiang Mai, and she was with her boyfriend who is also a pianist. That’s really it! We wanted to do something all together.”

Handsome, friendly and impossibly charming, Jonas is the kind of person who gets offered a free trip to Bali after a single glass of wine. Everything about him seems effortless, even blasé – he can be found at every party, surrounded by a gaggle of friends, flouncing and bouncing and staying out until dawn. Only his achievements, which he rarely talks about, allude to his impressive work ethic.

This year, at just 31, Jonas is in the process of being approved for “Statut d’Artiste Belge” – Belgium’s coveted official Artist Status – an exceptional honour which recognises career artists making a living solely off their art. He receives a special stipend between performance contracts that, once finalised, will remain for life.

So, while I’ve known Jonas now for quite some time, I felt compelled to learn a bit more about exactly how he got to where he is today. The story turned out to be far more interesting than I expected – a modern fairy tale of sorts, complete with castles, stallions, Prince Charmings, and…armed robberies.

Okay, let’s just start from the beginning, shall we?

The Early Years

Jonas was born in Ghent, Belgium on the day after Valentine’s Day, 1983. A few months later, he moved into a castle.

“My parents had no money and my dad was a wine sommelier at the time,” he says. “One of his customers was a count who lived in a castle (naturally) and they happened to have an empty top floor with, like, seven bedrooms. So they said we could move in!”

Jonas recalls a charmed childhood, frolicking through the castle’s sprawling grounds, a regular utopia dotted with greenhouses and lakes.

Then one day there was a sound at the door. Jonas’s mother was baking cookies – he remembers this clearly – the next minute, she and the elderly countess were being duct-taped to chairs by several armed robbers. The thieves roamed the castle, nabbing precious artworks, priceless heirlooms and Jonas’s mother’s car. “The cookies burned,” recalls Jonas. “That’s what I remember most.”

He was only about six years old at the time, yet somehow managed to set his mother free after the robbers left, cutting the duct-tape with a pair of scissors.

Unfortunately, the countess blamed Jonas’ family for the robbery, thinking them somehow involved, and things got awkward in the castle after that. The Depts decided it was time to move along.

Their next destination? A hippie commune called La Baraque in Louvain-la-Nueve, Belgium. But of course!

La Baraque began as a university project by several architecture students, and still exists today as a haven for alternative living, filled with geodesic domes and colourful art houses. Jonas remembers living in a mud hut and showering communally in a glass house.

“It was quite different from the castle…” Jonas laughs. “But it was an interesting place to grow up. I knew what hash was at eight years old!”

La Baraque is where Jonas’s younger sister Eva was born. It is also where Jonas encountered his first piano, left by a family friend who was quitting the commune. A big old ancient thing, complete with a Liberace-esque candelabra and gradations of coloured wax coating the keys, the piano was an instant source of fascination for eight-year-old Jonas. “Some hippies taught me to play a few songs – Beethoven’s Für Elise and that song on the black keys…what is it? I forget what it’s called.”

From there, Jonas’s passion for the piano only grew, and at age nine he advanced from his original piano instructor to a local government school. “But I hated my teacher,” he says. “I’m not really sure why, but I remember he had very fat fingers, his wedding ring all squished on, you know?” He giggles, then frowns. “We just didn’t click, which is really important. You have to click with your teacher.”

Fortuitously, his next teachers were a match: a pair of piano aficionados that Jonas looks back on fondly. First the wife taught him, then he switched to her husband at age 12. “I loved them,” Jonas recalls. “He was almost like a dad. I would spend whole weekends at their house, mow their lawn, stuff like that. They were very passionate teachers, very passionate about their jobs.”

When the Dept family eventually left the commune, Jonas was 12 and Eva was eight.

They spent the rest of their childhood moving around the country. “We just loved moving!” he says. “We moved at least once a year, and even when we stayed in the same house for a while we would change the rooms around – the dining room would become the bedroom, the living room would become the dining room…”

But even with his family’s rather haphazard lifestyle, or perhaps because of it, Jonas’ dedication to the piano remained steadfast. “My parents were supportive but never pushy. I loved piano lessons. Nobody ever had to force me to go,” he tells me. “I realised piano was my passion at age 13.”

His other passion was horses. The Depts somehow managed to finagle two black stallions for free from the boss of Jonas’ father (who was working as a translator at that time and who, like Jonas today, was a magnet for people who wanted to gift him things). Teenage Jonas would ride the stallions bareback with no reigns.

After applying and failing to get into the prestigious Royal Conservatory of Brussels (at age 16, mind you), Jonas enrolled in the Higher Institute of Music and Pedagogy in Namur, Belgium. But it was not a good fit, he says. “I didn’t love it because there was lots of other crap we had to learn, psychology of music, stuff like that. Also it was in a stupid city, very provincial.” He waves the memory away with a timeless Gaelic gesture.

That said, the experience in Namur wasn’t all for naught. “I came out to myself at age 18 after a gay couple flirted with me, aroused me and took away my virginity,” he recalls with his usual nonchalant air. “I knew instantly what I had never known before: I am gay! I came out to my family a few months later when I had my first boyfriend to introduce to them. It was a piece of cake. My mom said she kind of knew and that she never liked my girlfriends anyway. My dad said that when he had tried it himself in his early years, it hadn’t really convinced him. Then we had a fun party at home with my new guy.”

After living what may be the most idyllic coming-out story of all time, Jonas continued his studies in Namur, but soon realised he’d need to move on. So, just before completing his fourth year in the programme, he said his farewells and returned to the Royal Conservatory to try his luck a second time at the rigorous, week-long, three-part admissions process.

“It was so hard,” he says, grimacing at the memory. “For the first part, all 120 or so applicants sit in the same room, and there’s a guy playing like crazy on the piano. We had to write everything down as he played – all the notes, the rhythms, the tempos. Part two is sight reading, which is awful. You get 15 minutes to look at the music and then have to sing it along with a pianist. The third part is when you actually play your instrument.”

This time, at age 20, Jonas was accepted.

Of the years that followed, Jonas has only good things to say, recalling the arduous but friendly atmosphere with obvious fondness. “I loved the conservatory. You have to go way beyond what you think you can do and I was training ten hours a day, but loving it.”

I ask him if he ever got bored. “No!” he says, convincingly.

In 2007, Jonas completed his master’s programme and graduated. But rather than entering into the world of professional musicianship in Belgium, he made a rather curious decision. He decided to move to Chiang Mai, Thailand.

To Chiang Mai and Beyond

We’re a few beers deep now, Jonas dutifully recalling his past as I scribble furiously in my notebook. We take a break so I can give my hand a rest while noshing on some chicken satay and French fries, and chat about music. As it turns out, while Jonas can bang out Debussy without skipping a beat, he is utterly tone-deaf to pop culture and can’t even name a single one of the Beatles. “Mick Jagger, is he one?”

“Jingle Bells is probably the song I know the most lyrics of,” says Jonas. “And it’s six words.” I refrain from shattering his pride by telling him that there were a few more words after the opening line.

He starts to sing a song he made up: “Lobster on a stick, lobster on a stick, baby! Stuff the shrimp inside the crabmeat, ha HA!”

“I’m writing that down.”

“Good!” Jonas is the kind of person you just want to roll up into your handbag and take with you everywhere you go. He says he also knows a Mariah Carey song, but he can’t remember what it’s called, nor any of the lyrics. “I had a good kiss to it once, though.”

We return to the past.

“It was kind of a whim,” Jonas resumes, recalling his decision to move to Chiang Mai. “After seven years of intense studying I was ready to do nothing for a while. My boyfriend at the time was moving here to teach, so I decided to come. I was not planning on doing music here. In Belgium, we think there are no pianos in Thailand!”

Luckily, a few months in, after a rather disastrous attempt at a TEFL course, Jonas found a job at Chiang Mai’s Santi Music School, where he began teaching piano, choir and music theory to children. At the time, there wasn’t much of a piano scene in Chiang Mai.

But in many ways, being in Chiang Mai during this time was a huge boon for Jonas, even if he didn’t know it then. During his two years teaching at Santi, he was able to do a few small piano recitals around Chiang Mai.

“I did one at Centre of the Universe – the pool!” he remembers. “It was really weird. The wind was blowing the music sheets away, there was rain…the kinds of things that would never be accepted in Europe.”

He tilts his head, looking thoughtful. “But here, it was okay. Here, it’s more human. The freedom you feel when you are an expat is like nothing else. Nobody knows you, so no one can judge you.”

In order to make a living as a performance pianist in Belgium, Jonas says you have to be “really, really, really on top of the game” – win competitions, claw your way to the top, that kind of thing. “There are thousands of concert pianists there. Gigs are booked two years in advance. So I’m certain I wouldn’t have made it there. I would have become a teacher like everybody else.”

In Chiang Mai, Jonas stood out. Not long after his concert at the pool, he caught the ear of Mom Luang Preeyapun Sridhavat, owner of the prestigious Chiang Mai Ballet Academy, and got a gig playing piano for their upcoming dance exams.

With that, he had found a new niche. He soon quit his job at Santi and began building a network out of Asia’s dance community – from Chiang Mai to Bangkok to New Zealand to Australia to Singapore to Malaysia, the contracts just kept coming. “There is no competition!” he says. “Most people who play the piano don’t even know about these kinds of opportunities. Playing piano for ballet can be a career.”

And today, for Jonas, it is. He’s on the list of official pianists for the highly prestigious Imperial Ballet and the Royal London Ballet, and can pick and choose his assignments. He spends the rest of the time developing his own work, both solo recitals and Six Hands performances.

After well-connected Chiang Mai friends Donjai Srivichainanda and Marisa Marchitelli formed a production company just for him called M&M Productions, Jonas’s performances really took off. Marisa added visuals to go with his arrangements and the trio began organising events from Rachamankha Hotel to 137 Pillars House to Sangdee Gallery to Chiang Mai University.

“I like people to go to a concert and relax, have a drink,” says Jonas. “I want them to enjoy themselves, have fun and not be intimidated.”

Onwards and Upwards

Jonas’ most recent performance, which hasn’t happened yet as I write this but will have by the time you read it, will take place at Maya Lifestyle Mall’s rooftop. It’s special not only because it’s being organised by your good friends at Citylife, and raising funds for the Northern School of the Blind, but also because it will mark many firsts for Jonas: his first contract under his official Belgian Artist Status, his first time performing his own music, and his first time collaborating with his little sister Eva, who is now 27 and a filmmaker based in Brussels. She’ll be doing the visuals, which will be shown on an enormous screen behind Jonas as he plays, overlooking the mountains and the city lights twinkling below.

The performance is also a return of sorts – Jonas’s first Chiang Mai show in over a year. Recently, he’s been living the majority of his days in Bangkok (that is, when he’s not travelling the world, playing for ballet exams).

“Right now I’m finding my balance between Bangkok and Chiang Mai,” he says. “I’ve always considered myself a city boy and a nature boy.” Indeed, David Bowie’s rather obscure “Nature Boy” is one of the only karaoke songs Jonas knows.

His biggest dream of the moment is to put together a show that he can take on the road and perform more than just a few times, hopefully internationally. Recently, he was contacted by a top executive in Singapore who wants to make him the next Richard Clayderman.

Of his life so far, Jonas has no regrets. As usual, he is confident but humble. “I’ve been quite lucky. I’ve been in the right place at the right time.”

And of the future? “I really don’t know! But I know I’ll never retire. I’ll be a musician ‘til I die.”