Underdog

Citylife interviewed three people in Chiang Mai who have had to overcome great obstacles in life, only to achieve their dreams. We think you will find their stories as fascinating, and encouraging, as we did, and hopefully we can all learn something from their strength and confidence when up against the odds.

The Fighter

At 13 Pornchai ‘Pel’ Puttapoun was told by his parents that they had no choice but to ask him to leave home. It was either him or his brother, his dad told him, as they just didn’t have the money to support two children. Pel left home.

A few years later he was earning up to 45,000 baht a fight as a Muay Thai boxer, fighting at Bangkok’s famous Rachadamnoen Stadium. After several fights Pel returned home with a present for his parents, who were still struggling to make ends meet. “The proudest I felt was when I bought my mum and dad that car,” says Pel.

But the first couple of years on his own weren’t the best days of his life, says Pel. “I went and lived at a boxing camp and went to a free school,” he says, and explains that life wasn’t easy. “At first it was difficult, I lost hope, especially when I compared myself to other kids with families,” he says, but adds that now says he’s ok, and tells us that his experience has actually made him stronger.

At age 24 Pel trains hard and still wants to become one of Thailand’s great boxers. “But I need a back up plan, because when I stop boxing I will need a way to earn money,” Pel says, “so I got a loan and started studying media and communications at Rajabhat University.” He hopes to graduate and begin a career as a journalist, failing that, he will teach.

“You’ve got to be disciplined,” he says concerning Thai professional boxing, and adds that he always stays focused. Pel still doesn’t have a real place to call his own and lives where he trains at the Rattana boxing gym in Chiang Mai, but he seems content with that, and at least he’s never too far from a pair of boxing gloves. “I’m always ready for a fight,” he says.

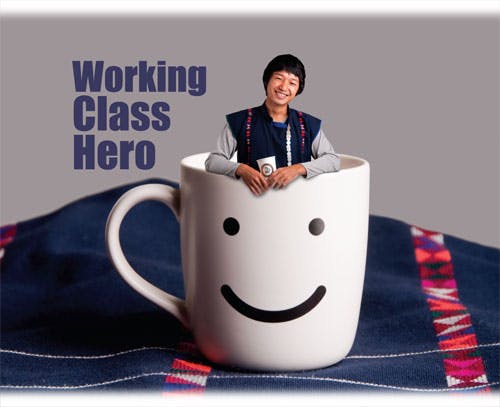

Working Class Hero

Lee Ayu Chuepa is the founder of Akha Ama Coffee, a ‘fair-trade’ coffee that has warmed the hearts and palettes of many. Lee was born in Mae Chan Tai in Chiang Rai, and brought up in an Akha village. “I’d never been to the city as a kid,” says Lee, “but I told my parents I wanted to study.” And so Lee began his journey. At first at a temple in Lamphun, where he learned to speak Thai and some English, and later onto university, a feat none in his village had ever achieved.

“It was challenge in my life. I had to support myself, I had to confront language barriers, and integrate into a bigger kind of society,” says Lee on leaving his Akha village. “I became a temple boy and started going to monk chat in Chiang Mai. There I began talking to foreigners so I could improve my English.”

Lee finished high school and became a member of various youth groups and organisations in Chiang Mai, including UNICEF. “I wanted to do something for society, but I didn’t know what,” says the young looking 26 year old, and explains how he went on to study English at Chiang Mai Rajabhat University.

“I did an internship at Child’s Dream Foundation, and then I became full time staff.” But Lee had a dream of his own, and after receiving a social entrepreneurship grant he started Akha Ahma coffee in 2010.

“The idea was to support the farmers from my village,” says Lee, adding that he knew they weren’t receiving a fair price for their coffee. He also mentions that monocropping, which had been practiced to support demands from large companies, was dangerous. “It meant that if the price of the crop fell, then the farmers suffered, but if they had multiple crops all year round then there would be less risk.”

“The farmers were working 365 days a year and had no money. Nothing ever changed for them. They had no negotiation skills, and they didn’t understand their bargaining power,” says Lee of his fellow villagers.

“My parents lived just with nature, they didn’t even understand the concept of money,” Lee says, but when it became the law that all Akha children must have a primary school basic education school fees had to be paid for, and farmers needed hard cash.

“I want to see all the children get a better education, I want to strengthen the economy of families,” says Lee, adding that sustainable agriculture and multiple crop farming have now generated a regular manageable income for his village. And at least they are getting a fair price for their coffee. Lee has helped to enhance production skills, and has marketed his coffee so well it is now sold all over Chiang Mai and beyond. It has also been chosen for the World Coffee Events twice from thousands of other coffees around the world. “It’s in such high demand these days there is not enough supply,” says Lee, and adds that now the farmers dictate the price.

“When I go back home now I see people smiling, kids playing,” Lee says, ‘I’m not really a business man, I’m more a social worker in the village. It wasn’t all about business, it would never have happened if I weren’t helping the people in my village.”

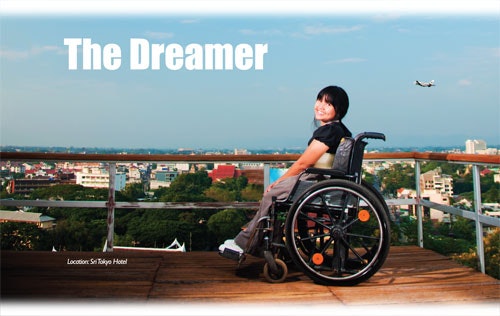

The Dreamer

Orapin Paiponganurak, 34, was only seven years old, and living with her mum and dad in their Karen village near Mae Sariang, when she started to feel excruciating pain in her back and joints. Within a matter of months she could not walk, and it was too painful for her to be moved at all. “My mum and dad didn’t know what to do,” says Orapin, sitting across from us in her wheelchair, “and they had to work. My dad believed the witch doctor could cure me, but my mum wanted to send me to a hospital. She feared taking me as she couldn’t speak Thai and thought she might get some blame for not taking me earlier.”

Orapin may have stayed bedridden for much longer if a doctor hadn’t visited the village for a healthcare talk and been told about her. The doctor immediately took Orapin out of the village and sent to her Suan Dok hospital where she saw an orthopedic specialist. “I found out I had Spondylitis (a rare vertebrae disease) and was told with surgery they would cure me.” But after two failed attempts and a lot of physiotherapy she was still in great pain and couldn’t walk. She tells us that at the time all she wanted was to go home back to her Karen village, “but,” she says, “my family never came to collect me. I didn’t know why.”

Only by sheer chance did Pat Kemasingki learn about Orapin, twenty years ago, when her maid told her she was delivering fabric to a girl in the hospital. After visiting Orapin, Pat moved her to McKean hospital where she helped sponsor Orapin through various physical therapies and pain management strategies, while also offering her money for making cross stitch cards. Orapin expanded her home-business by selling bead necklaces while studying and graduating from school. Pat helped Orapin find sponsors, a husband and wife from Germany, who sent her 2,500 baht a month for many years and visited her regularly, fueling her interest in learning English.

Orapin ended up living at McKean for many years, being given one of the old colonial-styled houses initially built to house lepers. Her family eventually came to see her, and admitted that the leprosy had frightened them away, and she even returned to her village at one point, but they were simply not equipped to take care of her and, even though Pat built a room for her under the house, the villagers thought that she brought bad luck, especially as her brother was also handicapped. A couple of years ago, there was a change of administration at McKean and a former social worker from McKean invited her to stay at his new foundation. The Tawanchai Foundation, where Orapin now works breeding fish and poultry, while also still making bracelets, is her new home.”With this money I paid off my bills at McKean, and I also saved a little bit of pocket money once the bills were paid,” says Orapin.

Oripin’s dream came true when she finally managed to save enough money to fly her mum and dad to Hua Hin for a holiday. “It was the first time they ever saw the sea,” she says, and certainly the first time they had all been in a plane.

She may have fulfilled that dream, though Orapin says there is one more thing she wants to do. “I hope my condition will improve. And when I am more self-reliant I plan to visit Germany and thank Bernadette, a journalist (whose husband is now deceased) for helping me.”

There is no self-pity here and while she was dealt a pretty tough card at birth, she is simply getting on with her life and fighting for what she wants out of it. This past September Orapin flew to Bangkok to attend a course in connection with her work for a degree at Sukothai Open University in child care, from where she is soon to graduate.