You may be surprised to learn that Chiang Mai is well on its way to submitting its final dossier to UNESCO in our bid to become Thailand’s first living heritage city. It has involved an extraordinary amount of work by people from many sectors. And while UNESCO suggests an indicative timeframe of ten years for the preparation of nominations, and we have been at it for just over three years since we were placed on the tentative list in 2015, those leading the charge say that they may be ready to submit in as little as a year’s time. If accepted, this would be a great honour and boon for Chiang Mai; if not, the process itself has been an invaluable asset to the development of the city…and we will still have many years to regroup and reapply.

According to Dr. Richard Engelhardt, a former Regional Advisor for UNESCO, who has helped around 200 sites achieve the coveted status over the years, this ambitious mega project has the ultimate goal of strengthening and benefiting the roots of the city. “It is a long-running fight against the rapid and unruly development of the city,” explained Engelhardt who is also a Chiang Mai resident and proving to be a formidable ally and asset to our bid. “Unlike historic sites such as Ayutthaya or Sukhothai, Chiang Mai is a living breathing city, with all the urban complications that goes with it. Therefore at the heart of this project are the people; it has little or nothing to do with providing economic benefits for external people who come to Chiang Mai to make a quick profit by running tourism-related businesses. We want to see a quality of life that is greener, cleaner, quieter, less polluted; a continuation of the generations of development that has gone into what makes Chiang Mai unique.”

Engelhardt explains that each year a country can propose only one site to the committee which will only consider 35 sites worldwide. Chiang Mai is not the only site to be on Thailand’s tentative list and he urges authorities to avoid having Thai sites jostling against one another, but to follow China’s model in queueing them up by priority and possibility. “China has queued nearly 100 sites to be submitted over the next 100 years,” he said, while explaining that Thailand still has yet to decide which site would be submitted next. That decision is made on a national level and will depend on which site is most likely to be considered.

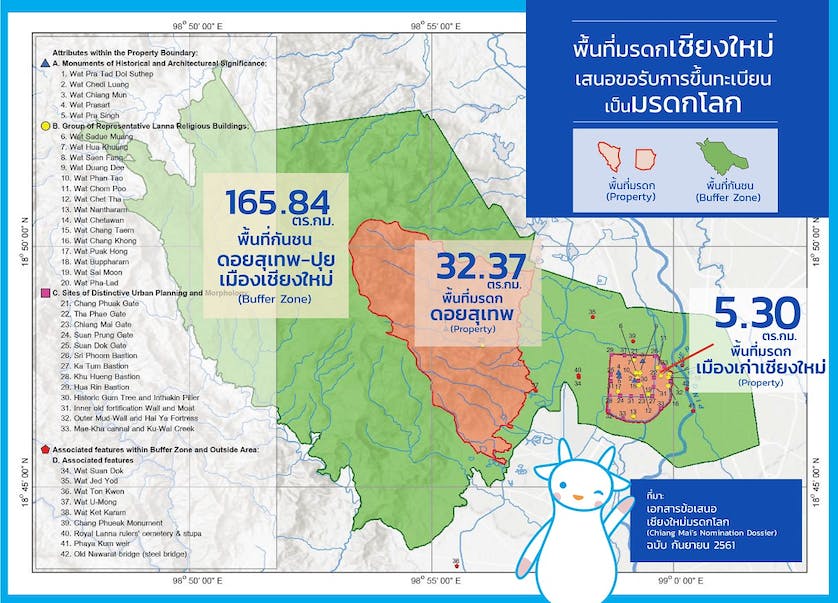

Chiang Mai will be proposed for inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List as one property consisting of two complementary components: the historic old city extending to the outer walls and moat including Mae Kha canal (5.30 sq.km.) and the sacred mountain of Doi Suthep, within a buffer zone which covers much of the Doi Suthep-Pui National Park area (165.84 sq.km.). It is a little known fact, but the national park was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in 1977, which means that it is already in compliance with some of the organisation’s rigorous conservation standards.

“A dossier comprises around 1,000 pages,” explained Engelhardt, an old hand at compiling and scrutinising such dossiers. “There are three major sections — the narrative, proof of authenticity and integrity, and the management plan.”

Our Story

The challenge of crafting a successful nomination, according to Engelhardt, is threading together the chosen criteria into a compelling story of “outstanding universal value” — that is to say, a local narrative with global significance. “The committee wants to know how a nominated town has contributed to a global story of interest to the entire international community. In the case of Chiang Mai, I think the components of our story are very clear. First and foremost, is Chiang Mai’s original and unique urban form, designed by the famous Three Kings: Mengrai, Ramkhamhaeng, and Ngam Meung. This ’new city‘ enabled a new, ethnically-diverse and culturally-rich, society to take shape — a civilisation that today the world recognises as Lanna Culture. Lanna Culture is, of course, one of Southeast Asia’s most distinctive cultures, especially renown for gorgeous decorative arts and resplendent temple architecture. To understand how this all came to be, it is important to contextualise the development of Chiang Mai within the historical events swirling around the region when the Three Kings founded their ‘new city‘ in the late 13th century CE. At this time, Kublai Khan, all-powerful Mongol emperor of the newly founded Yuan Dynasty of China, was embarked on a ruthless campaign to expand his territory by systematically attacking the older smaller kingdoms of South East Asia. The Chinese Mongol army had just sacked Bagan and it was obvious that next on the list was to be Sukhothai. Sukhothai’s King Ramkhamhaeng needed an ally willing to build a fortress strategically closer to China, because he knew that if the invading forces made it down into the Ping and Mekong river valleys, not only Sukhothai but all the smaller Tai kingdoms to the north would be lost. The Three Kings concluded a strategic alliance and built the ’new city‘ of Chiang Mai to be the much-needed advanced fortified settlement to thwart any possible incursion by the marauding Mongols.”

Engelhardt explains that what made Chiang Mai so unique was the combination of urban design influences which were drawn upon to build the city. “First, like most cities in the world at that time, spiritual beliefs and cosmology greatly influenced urban planning. The choice of the setting of Chiang Mai at the foot of the sacred mountain of Doi Suthep, was based on ancient local Lawa beliefs in the power of the mountain’s nature spirits. These indigenous Lawa beliefs were reinforced by Mon cultural beliefs in the protective power of the Buddha, especially the protective power of the Buddha relic enshrined on the mountaintop temple of Wat Phra That Doi Suthep. It is also important to recall that, at this time, the famous Emerald Buddha was enshrined in Wat Chedi Luang at the very heart of Chiang Mai, making the new city spiritually invincible. Many of Chiang Mai’s unique cultural traditions and customs, originating from the time of its founding are still being faithfully followed today — for example, the Inthakin City Pillar ceremony. But in their wisdom, King Mengrai and his allies did not rely on spiritual power alone for their protection. Chiang Mai was designed using state-of-the-art knowledge in hydrological engineering derived from Khmer technology, thanks to the contribution of King Ramkhamhaeng to the new city’s urban design. Chiang Mai’s Khmer-influenced water management system, was highly sophisticated and showed great understanding and foresight, thus enabling Chiang Mai to continue to function as a sustainable city even as it has grown exponentially in size from the small town of the 13th century into the urban metropolis it is today. And lastly, Chiang Mai’s high walls, strong gates, and deep moat were modeled after the architecture of fortified Chinese military garrison towns. It is this confluence of disciplines that makes Chiang Mai an unique city, not only in the north of Thailand, but in the entire world — and therefore part of the global story of urban design and development, worthy of inscription on UNESCO’s World Heritage List.”

The Chiang Mai story doesn’t end with the 13th century, according to Engelhardt. “The 18th and 19th centuries saw an explosion of art and architectural abundance in the city. Again, Chiang Mai’s story is both unique and globally connected. As Europe’s shipping empires grew, the great ships needed big, long, sturdy masts. And there was no other wood better than teak. Chiang Mai had an abundance of teak and unlike other commodities there was no shortage of it in local supply. And because there was no immediate need to reinvest in planting teak, as the trees were abundant in the surrounding mountain forests, so Chiang Mai’s local teak merchants accumulated vast surpluses of wealth — wealth that they reinvested in the lavishly beautiful temples of the city that had made them rich. The result of this is what we see when we look around at gilded pagodas and glittering temples — a surplus economy based on rich profits made by local teak merchants who supplied valuable, strategic material vital to the development international shipping and commerce. Understanding this, we can understand that Chiang Mai’s long and continuing story of prosperity isn’t just a temporary local phenomenon or a consequence of the city’s link to regional economic fortunes, but because the city had a far greater reach as an indispensible link in the chain of global trade and development.”

Always Verify

“Over the past three years I think we have produced about 20 doctorates’ worth of research to defend our application,” said Asst. Prof. Komson Teerapapong, from Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Architecture, one of the many researchers tasked with writing and verifying submitted data on the city. “We can’t just say that our city was founded in 1296 or that this temple was the oldest in the city; we have to prove it. UNESCO’s standards and values are very high.”

A total of 33 attributes have been chosen to represent these values, including all our city gates and bastions, the moat and many temples.

Two words repeated by all people interviewed by this article, are integrity and authenticity — the second section required in the World Heritage nomination dossier. “Chiang Mai must deliver proof, challenging all of the history books to prove its authenticity,” added Komson. “As to integrity, this is the hard bit as it is about showing how intact a building is. Wat Phra Singh, the wall, or gates for instance, have been renovated so many times over the centuries, so you have to look at how they have been repaired, and what techniques used to rebuild.” He goes on to explain that the World Heritage Committee has adjusted its guidelines over the years, giving space for living cities which have evolved with societies. “Now that we have declared our valuable assets, the next question is how to preserve it. And with that comes the management plan. As a nominated living heritage, the concept of sustainable development will be pulled into the plan along with the conversation,” added Komson.

The Hard Part

“There are some people who think that Chiang Mai is too bruised to be considered a World Heritage site,” said Suwaree Wongkongkaew, Director of the Chiang Mai City Arts and Cultural Centre who is now the interim head of Chiang Mai’s World Heritage Office. “They don’t see how we can push for the status within the current mechanisms of the city management plan.”

The third part of the dossier involves the plan; basically how will the city manage itself so that it complies with UNESCO’s stringent guidelines? Here there is good news and some cause for concern. According to Engelhardt the good news is that there is national will in supporting this bid. The head of Thailand’s World Heritage Committee is the Deputy Prime Minister, crucial in liaising often-discordant departments. “Thai agencies each have their own mandates and responsibilities and so inter-agency coordination is a challenge,” said Engelhardt, “but with a top-level order setting a common goal, yes, it is possible. The national government has said it wants to pursue World Heritage status for Chiang Mai, and the local authorities have also been clear in wanting this. The biggest challenges come because each department has its own timeline for its development plans; case in point the Department of Public Transportation, which has recently released a 20 year plan to build a mass-transit system in Chiang Mai, with one underground route going directly under the old town. This transport development plan doesn’t necessarily fit well with the more slowly-evolving vision for the conservation of the old town’s historic values, but the transportation plan already has an allocated budget and is moving ahead, regardless of a possible conflict with conservation values. Top level management will be required to get everyone on board and working to the same plan. UNESCO expects well-coordinated, long-term management as a basic condition for all World Heritage properties. Indeed, demonstrated proof of good site management is the third pillar required of all successful nominations for inscription on the World Heritage List.”

To date, the project has received positive responses from the Department of Public Works and the Town and Country Planning Office Chiang Mai, both pledging to collaborate. The Chiang Mai Provincial Office for Natural Resources and Environment will also play a significant role in managing the Doi Suthep property and the mayor has pledged his full support and the Provincial Electricity Authority has already offered to take care of cleaning up the messy wires. Impressively, to date, it has been the office of the Provincial Administrative Origination which has funded much of the work done in preparing the dossier, including numerous study trips to other world sites so key players can understand and support this vision.

“The challenge will be to create a management plan for the protection of the city’s heritage values that will meet World Heritage requirements within the current framework of the Thai government’s management system for the governance and development of urban areas,” said Engelhardt. “The fact is, that kind of management plan doesn’t yet have an operational reality within the existing structure of the Thai development code,” he said, “with the nomination of Chiang Mai to the World Heritage List, Thailand is charting exciting, promising new territory in urban conservation planning and management. This will have an important impact in the conservation of not just Chiang Mai, but of all the many other beautiful historic cities and towns of the Kingdom.” Engelhardt also points out that the responsibility for good conservation management is not the responsiblity of government alone. In a living heritage city there are many stakeholders, each with a legitimate concern for and responsibility to contribute to the effort. In Chiang Mai, with its many beautiful Buddhist temples identified as important attributes of the city’s ’outstanding universal value‘ as a World Heritage, the monks, or sangha, as custodians of many of the most important and iconic of the sites contributing to the value of the historic town, also need to be brought into the fold. The beleaguered (and fabulously wealthy) sangha has been under attack in recent years for its lack of transparency and oversight and to date appears ambivalent to jump onto the World Heritage bandwagon.

All Aboard!

At the end of the day, however, this is going to end up being a city-wide effort, and the Chiang Mai committee has an uphill battle not only explaining what it all means, but what intangible benefits we will all reap.

“I don’t really understand when people keep asking me what they will gain from us being a World Heritage site,” said Ajirapa Pradit, the Project Coordinator, pointing out that everyone needs to look beyond pocketing from the city. “What we are gaining is a system that will preserve our values and help us to develop sustainably,” added Assoc. Prof. Woralun Boonyasurat, Director of the Social Research Institute, Chiang Mai University.

The management plan is a mechanism which will outline the preservation and development structure of the city. The priority of the plan is community empowerment. “There will be no point preserving our values if there is no longer a community,” said Ajirapa referring to the alarming number of locals in the old city selling off their land to live comfortably elsewhere, leaving the city to be filled with outside developers and tourism-related businesses. No one wants to see the city turn into a tourist playground, especially with the current nine million tourists a year coming to Chiang Mai expected to double in a decade, and part of the plan may have to include incentives such as tax breaks to appeal to remaining locals.

Over the past three years, the committee has successfully reached out to many location-based communities, setting up workshops and town hall meetings to explain the project and its many benefits. “We have had groups of sex workers and the disabled come and show us their support,” said Woralun, saying that most of the feedback has been positive. “There are still many communities which we have failed to reach,” said Suwaree. “The expats and Bangkokians who have made this their home need to join in the conversation effort, too. These are groups we are struggling to find common ground with and reach out to. But we want everyone’s participation because this decision will impact everyone in the city. This process will require the government, local authorities, residents, institutions, the private sector, the sangha, and everyone else to come together.”

“If we get the community on board, then we can all decide on things such as whether to allow non-resident vehicles into the moat,” explained Ajirapa. “The community plan will allow residents a more active role in deciding how they want to live. Their suggestions will then be submitted to a committee and we will have more local autonomy. This will be the first model of its kind in Thailand.”

If all goes as planned, this dossier will become our city’s management masterplan which, if accepted, will come with the ongoing support of UNESCO’s professional team of urban planners to help implement it. Waste water systems, electric cables, transport and congestion, proliferation of signs, public transport and all other issues which have long been eyesores and heartaches for we residents could, potentially, be managed in a more efficient and more sustainable way.

And pollution, I hear you ask? Important as this issue is, it is not directly relevant to Chiang Mai’s bid for World Heritage status. As explained by Engelhardt, pollution may make some temples a bit dusty, but it doesn’t directly impact on the integrity or authenticity of the 33 proposed attributes. However, a well-coorindated conservation management plan that makes our city cleaner, greener with less congestion and reduces pollution, will inevitably have a powerful impact on the way we manage all of our urban development issues — collectively, together, and for the benefit of all residents of Chiang Mai, today and into the future.