But it was the incessant phone calls and messages from home, increasing in frequency and urgency that pressured her return home. She didn’t want to, she knew that she wouldn’t be earning a living back in her remote village of Mae Jae in Khun Yuam District of Mae Hong Son. But her family told her that the village was shutting down, that no one was allowed to enter unless they go and find a hut in the forest or paddy field to self-isolate in for a fortnight. Pam was living in relative comfort and had a good job paying good wages. She was guaranteed full salary, room and board for the duration of the pandemic and not being able to go anywhere she could have saved up quite a decent amount of money had she chosen to stay.

But she decided to go to quell her family’s fears and to support them through the pandemic. Pam’s husband, who works as a martial arts instructor in Chiang Rai, agreed to also return with her. Her family found a shack in the middle of a rice field for the couple, put basics such as mosquito net, cooking materials, a mat and some pillows in it and Pam and her husband headed home with a few bags of groceries and necessities to sustain them for the duration of the fortnight.

They spent two weeks alone in their hut, every day or so waving and talking to other couples in other huts dotted across the mountains – mainly younger members of the village who had been recalled from Chiang Mai, Bangkok or even Phuket.

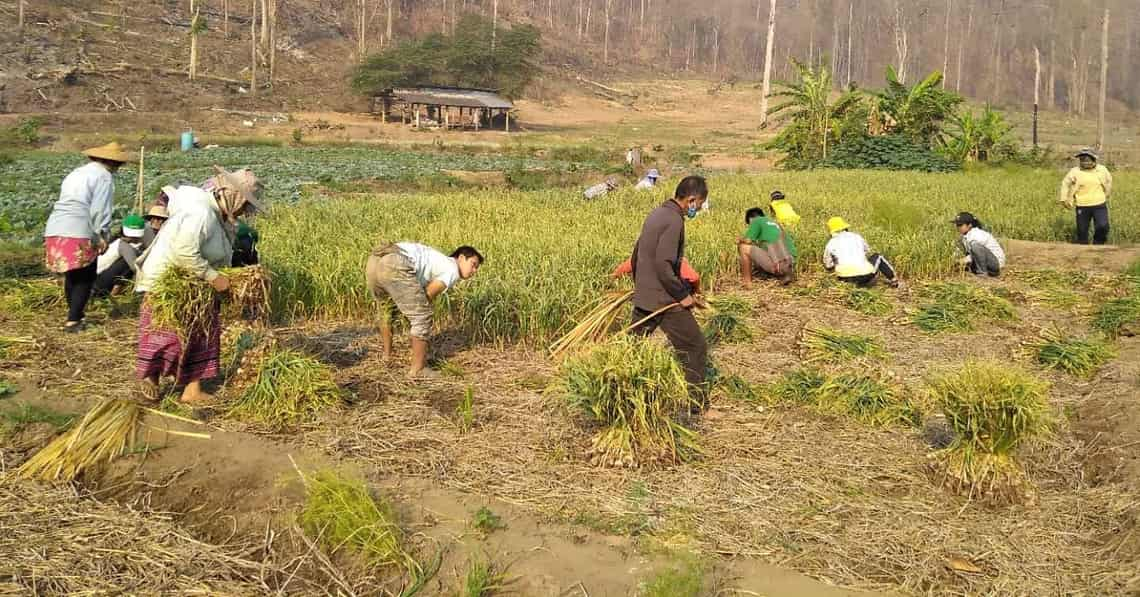

After a fortnight the pair were allowed into their village and returned to their family home where the couple have been living with Pam’s widowed father, helping him till the land.

Today she sent in her notice to her employers in Nimmanhaemin, having decided, along with about half of the 20 or so COVID-refugees to Mae Jae, to stay home and see if they can make it work.

“One of my friends has opened the first noodle shop in the village,” said Pam to Citylife as we tried to converse on one bar, Pam climbing a tree at one point to get a better signal. “It doesn’t look like much but she leant how to cook in the city and it’s so delicious, we are all loving it.”

Others in the village are bringing some of their modern ideas home, Pam says, some talking about opening a homestay to attract future tourists, others talking about growing organic produce such as coffee and opening a café one day. There are talks of forming a cooperative with other young farmers choosing to stay in other villages in the area.

“It was tough at first as it was so hot and dry,” said Pam. “It was very hard to hunt and forage then and we were running very low on any food supplies. But now the rains have come it’s wonderful. I am really enjoying doing all the things I did all those years ago in my childhood. We hunt and forage and we are growing vegetables, and we are doing it all together as a village. We eat tadpoles, frogs, bamboo shoots and find whatever we can in the forest. It is easy living in the city to forget how to live on the land, but I am really enjoying it.”

Pam has had a teachers’ licence for the past two years now but couldn’t get a job, hence her stint as a domestic worker. She has now been offered a job as a teacher in the village paying her 3,500 baht a month (her city job paid 9,000 baht) but she has decided that that is enough. “I can help my family farm and we can make extra money that way and I am happy to teach here until I can get a good teaching job placement.”

Even though Pam’s village is no longer closed off, anyone returning still has to go and find themselves a remote hut and self-quarantine for two weeks. “No exceptions,” said Pam.