On its surface, Can Do Bar seems like your average after-hours watering hole. Shelves of liquor bottles shimmer under neon signage, and the latest pop chart-toppers drift out from the loudspeakers. Despite its comfortingly nondescript appearance, it is the only bar of its kind in Chiang Mai: it’s run entirely by sex workers.

While its uniqueness is notable, the women who own and work at the bar hope to eventually see more establishments like it, because the space they have created is safe, community-run and fairly managed. They also want make it clear that their employment as sex workers at Can Do Bar is their choice. And they make the rules.

“Here, the women aren’t forced to dress a certain way. We’re not forced to drink,” says Neena, one of Can Do Bar’s longtime employees. Can Do Bar’s rules are in place as protective measures against the unjust treatment sex workers often experience when hired at other places. Other bars require that sex workers consume alcohol while on the job, demand that they maintain a certain weight, and have a number of additional strict policies that exploit them.

Sachumi Mayeo, another woman who works at Can Do Bar, explains that in many of the karaoke, massage and bar venues that employ sex workers, “for every minute you come late, your salary is cut. Every time you wear the wrong uniform pieces, your salary is cut.” In other industries, labour laws protect staff members from these illegitimate policies, but because sex work is criminalised in Thailand, women like Sachumi are at the whim of their controlling employers.

The criminalisation of sex work can malign these women into feeling trapped in dangerous situations without proper legal resources. “If a customer doesn’t pay us or treats us badly, we can’t go to the police,” says Sachumi. “If the boss forces us to drink but we refuse, where can we go?”

This is why the priority of the Empower Foundation, the organisation behind Can Do Bar, is the decriminalisation of sex work. Sachumi makes an important distinction: “We don’t want legalisation, we want decriminalisation. We don’t want more regulation. We just want to work in the same way that other workers do.”

Decriminalisation could have a dramatic impact on the lives of sex workers by granting them the freedoms to which they are entitled. “We’re people, but the law doesn’t see us as people,” says Sachumi. “Because the law doesn’t recognise sex work as work, we don’t have freedom. We don’t have rights. The law says that sex work isn’t work, and contributes to the perception that sex workers are pitiful victims. We don’t want to be pitied; we want justice.”

The women of Can Do Bar are all too familiar with the public stigma surrounding the decriminalisation of their livelihood — and the fear that accompanies it. “A lot of people are afraid it would be chaos,” says Sachumi.

Another issue inevitably arises in our discussion about sex work: human trafficking. The industry of sex work is sizable in Thailand: a 2014 UNAIDS report estimated 123,530 sex workers within the country. Yet there is little nuance in the way the government addresses these issues; sweeping raids of the places where sex workers are employed involve arrests of all who are present, even those working consensually.

Sachumi and Neena emphasise that human trafficking should not be conflated with all sex work. By their account, they have actively made this career decision, and say they are better off for it.

They have found a helpful support network of like-minded women at Can Do Bar, and within the organisation that founded it: the Empower Foundation. Empower’s website describes itself as a foundation dedicated to improving the lives of sex workers through advocacy, education and personal mentorship. In the thirty years they have been active, Empower has developed a wide range of programme in cities around Thailand for sex workers, including English and Thai language classes. These women often struggle to afford English classes offered through traditional language programme, and many have faced discriminatory treatment in those environments. They recounted the story of one woman who was prohibited from going to the bathroom during class when someone there found out about her job.

The organisation also provides legal services. “Women have the opportunity to come here and learn about the law and what their legal rights are. They can’t easily do that other places,” says Amornprapa Seechana, a legal volunteer at Empower.

Neena enthusiastically advocates for herself and her place of work. “Can Do is very important for sex workers, because here, we have an opportunity to work safely and with as much justice as is possible to access under criminal law,” she says. “It’s also a place where people who aren’t familiar with sex work can get access to an education about it in a way that’s available in very few places.”

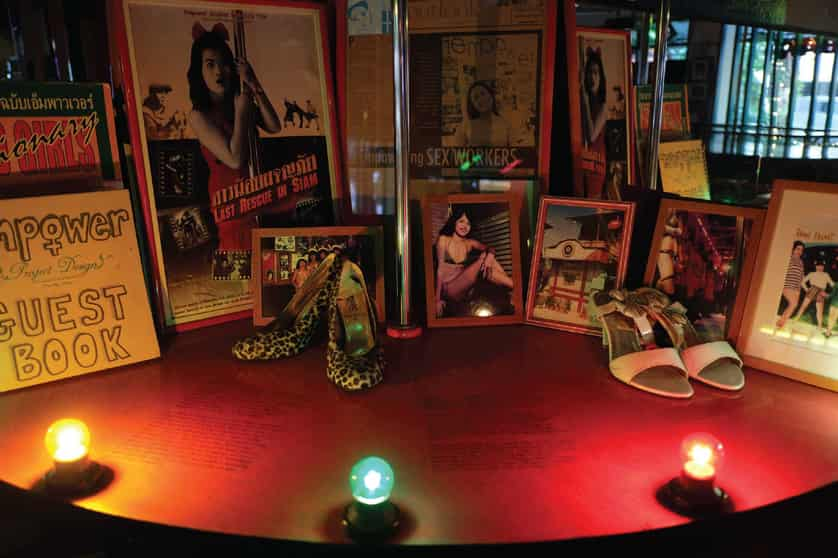

Resources designed to educate people about the realities of sex work take a number of different forms at the bar. Upstairs, there’s a room with a bed, a couch and a small number of seats arranged for an audience. This is Reality Theatre, designed as an educational performance space to showcase sketches written and performed by Can Do Bar employees about the mundane, humorous, frustrating or humorous experiences they have while working.

There’s also a bookshelf with texts about sex work, including a dictionary that contains definitions of words that are frequently used — and misused — when sex work is discussed publicly. For example, as a commentary on the way sex workers are arrested for their work, the definition for the term “victim” is, “Society sees sex workers as victims, and society has no place for victims outside a cage.”

This dictionary also contains a glossary of frequently asked questions. “What does your family think about what you do?” is translated as, “They must be so devastated that you do this kind of work.” And the question, “When did you start doing this work?” is listed as implying that it must have been an absolute low point for someone to turn to sex work. Many members of Empower are accustomed to hearing these questions, but they hope to encourage curious observers to think about the underlying implications before they ask.

Neena made the choice to work at Can Do Bar not because she was out of other options, but because it would support the life she wanted and because she did well in her work. “I used to work at a hospital,” Neena says. “When working there, to make the kind of money I wanted to support myself and my parents, I would need to work sixteen hours per day. But when I went to work at a bar, in just half a month, I was making better money than working a month at the hospital. So I left the hospital, and I started to work full time at the bar. It changed my life. Here, I can support my parents and my siblings’ education. I’ve done this for three years now and my life has continued getting better every year.”

The nighttime hours of sex work have also allowed Neena the freedom to take a job during the day at a guesthouse, and she was worked as a tour guide recently as well.

She says all of her jobs have included some aspects that were easy and other that were more difficult. In this job, Neena says, “a lot of it is about taking care of customers. We need to listen to them, talk with them, take care of their feelings. If they’re crying, we need to comfort them. Sometimes, a sex worker will go with a customer and not even have sex, but they still pay, because it’s work. We give our time.”

“We’re like therapists,” Sachumi chimes in.

Can Do Bar is helping Neena prepare for her future, and she imagines that her future will still include sex work. She aims to one day own a bed and breakfast, as well a bar that she will model after Can Do Bar, where sex workers will be treated justly. Sachumi’s hopes for her future are equally defined: to find security in sex work. “We don’t want to feel like we have to run from the police,” she says. “We don’t want unfair salary cuts. We want to work in a place where we can be safe, where there are benefits, and where the work is considered work.”

Reciprocally, the women are shaping the future of Can Do Bar as well. “Here, we can listen and we can learn, and then we can become teachers,” says Sachumi. She took Thai language classes at Can Do Bar early on, then progressed to becoming a Thai teacher herself. She also studied in Empower’s non-formal education programme for high school diplomas. Now, she is able to teach Thai at other foundations and in universities, and she leads the non-formal education classes at Empower.

Having a space where these women can come together to work in a safe environment and share resources for how to improve their industry has given many of them a better understanding of their own capabilities. “Becoming involved with Can Do Bar has built my confidence,” says Sachumi. “Everyone might have some level of confidence already, but it’s powerful when women learn to use that confidence.”

Can Do Bar

322 Chiang Mai Land

Chang Klan Road

Open Wednesdays to Fridays 6pm to midnight