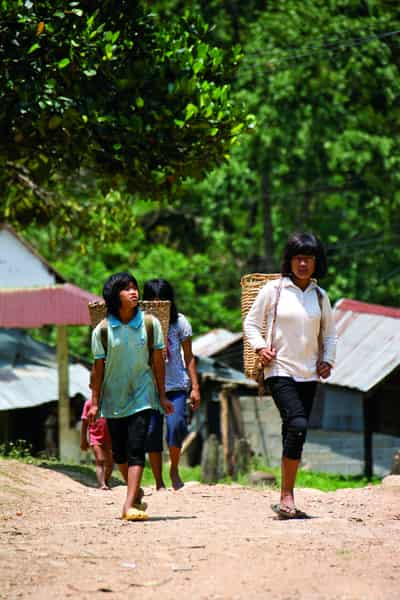

The land on the road to Ban Boonyuen is scarred. The rolling hillsides previously lush with teak and fruit trees now a barren horizon of dusty, brown mounds and scattered rice cultivations. I tightly hug each turn of the narrow road in anticipation of passing cars, but there aren’t any. The land is a shadow of what it once was, a dense jungle thriving with wildlife and an intricate ecosystem that supported the ways of hunter-gatherers for at least a thousand years. It is obvious, looking at the bare terrain that there’s nothing left to hunt; there’s nothing left to gather.

I had first heard of the Mlabri by stumbling across yellowleafhammocks.com, a social enterprise started by an American man that provides Mlabri villagers the means to sell hammocks online. The website boasts a beautiful video of the Mlabri weaving on a sunny day in Ban Boonyuen, an aerial time lapse of villagers laying out freshly dyed yarn in rainbow colours to dry in the sun, and a group of weavers giggling and roughhousing in one of their completed hammocks. A smiley missionary in the video acts as a sort of narrator, explaining how he and the American have worked together to make hammock weaving a tangible revenue stream for this community. The jangly guitar soundtrack and high definition video, professional website design and cheery missionary — it all looked great. But I couldn’t help but wonder, what’s really going on here? Am I just witnessing the dreams of others being imposed on an indigenous community? Is this what the Mlabri people really want? And so I set out to Ban Boonyuen with my questions.

The Mlabri have a nickname. “Spirits of the Yellow Leaves,” or Phi Tong Luang in Thai. Its origin is generally the only blurb of information you can find about the Mlabri without doing some serious digging. It goes like this: while moving through the landscape, the Mlabri would hunt and gather from specific areas for a few days at a time, building tiny structures of banana leaves as shelter. Suspicious of outsiders, the Mlabri had generally moved on before anyone could notice them, leaving only the fading leaves of their shelter, which turn bright yellow after a few days of being severed from a tree.

Because the Mlabri language is preliterate, their origin and history is not known in great detail. The first mention of the Mlabri was a description of a 1938 exhibition by Austrian anthropologist Hugo Bernatzik in his work “The Spirits of the Yellow Leaves,” an account accompanied by vivid photographs of his time spent hunting and foraging through the mountains of Phrae with a band of what would later be known as Mlabri. There is little mention in academia of the Mlabri afterwards, until a 1963 exhibition of archeologist and historian Kraisri Nimmanhaeminda who described his contact with a group of Mlabri and who later attempted to study the loose records of Mlabri language.

During the 60s and 70s rapid teak harvesting and conversion of the mountainous landscape into monoculture farms closed in on the Mlabri way of life. Traditionally, the Mlabri could use their knowledge of the forest to trade with local Hmong and Northern Thai villagers and retreat back into the jungle, picking and choosing when and how they interacted with “outsiders”. But as the jungle began to fade, their ability to trade and remain secluded from other communities became impossible.

Without the jungle, the Mlabri faced hunger and severe poverty. The only alternative was working with neighbouring villagers on rice, cabbage, or other farmlands, essentially assimilating into an outside world they had avoided for centuries. Being completely inexperienced with the idea of working for wages, and without any other options, the Mlabri were easy to exploit. A scene of the 2007 documentary by Danish filmmakers Final Cut Productions entitled “The Importance of Being Mlabri” accounts for the unfair conditions the Mlabri face working in the neighbouring farms.

“When I was a child we couldn’t find any food in the jungle, so we went to the outsiders, and they gave us some food,” describes an elderly Mlabri, seated in the middle of a dry cornfield. “They said ‘Friends, work in our fields,’ and we said ‘We don’t know how my friend,’ they said ‘in that case, no food,’ ‘but our children cry for meat, we would like a pig,’ they replied ‘then work in our fields.'”

The man stops, and scans the large corn field with his finger, “If you took a pig, you’d have to do a field this big. All of it. It takes a long time. Two people even, maybe a month.”

“They tricked us!” explains Chuwit, a middle aged Mlabri man, during another moment documented in the film. “They gave us a small pig and the work was huge! We then asked, ‘The work is finished, is our debt paid?’ ‘Oh no! Pigs are very expensive,’ they’d say, ‘your work is still not enough to pay for it. Three more fields and the debt is paid.’ Its Terrible! It used to be a BIG pig for a small field. Now its a SMALL pig for a big field.”

The labour agreements also required the Mlabri to remain near the farms, thus forming quite possibly the first Mlabri villages in their history, where the Mlabri don’t sleep under banana leaves anymore, and don’t approve of being addressed as “spirits” either.

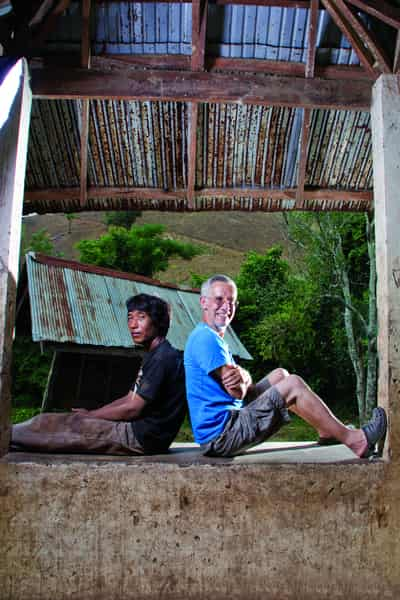

Ban Boonyuen is one of such Mlabri villages nestled deep in the hills about an hour outside of Phrae city. At the top of the village, beyond the bamboo and cinderblock houses of the villagers, sits a different looking house; the modest, but modern home of Americans Mary and Eugene Long who have lived among the Mlabri for over 40 years.

“I first heard about the Mlabri, or Yellow Leaf People, from a 1963 copy of the Journal of the Siam Society,” Gene explains. “At that time, many missionaries were seeking out people that never had the chance to hear the story of Jesus Christ, and that’s what I was looking for.”

“When I found them, it was 1979, their children were undernourished, they had those skinny limbs and big stomachs, they were frightened and poor. Some of them were shivering by a fire in the middle of the summer — they had malaria. I eventually learned how to test for malaria and was shocked to find so many cases of it, some of them just walking around that seemed fine, but they were positive.”

Though Gene’s initial motivations were to preach, he knew that even despite the language barrier, such an endeavour would be meaningless to the Mlabri given the state that they were in.

“If you’re out here, and you’ve got a guy shivering by a fire this time of year with malaria, and you say ‘Hey pal, God loves you, he loves you so much he sent Jesus Christ to die for our sins,’ well, that’s not really going to catch on. We decided to speak through our actions instead.”

Gene’s commitment to helping the Mlabri eventually led to relocating his entire family to the village. He raised his children in the village, built his home in the village, and together his family spent years piecing together the Mlabri’s beautiful, melodic, tonal language to gain insight into what the Mlabri thought and believed. The Longs have never held a Bible class or preached a sermon, there aren’t any Christians among the Mlabri that they know of. The Mlabri remain animists to this day.

The Long’s efforts mainly focused on alleviating unfair labour agreements, assisting with healthcare needs, and advocating for Thai citizenship for the Mlabri. After years of lobbying the Thai government, they were finally approved, giving the Mlabri access to many things including local boarding schools, the option to have seats in the local council, and the ability to start their own businesses.

The Long’s decision to live in constant contact with the Mlabri has not been without both secular and religious criticism. Their lack of emphasis on literal evangelism met with Christian critique claiming they were doing too little, while at the same time others claimed that their presence threatened the Mlabri way of life.

“I get it from both sides,” explains Gene, “I’d get it from the Christians and they’d say ‘these peoples’ physical needs are nothing compared to their spiritual needs’ but the truth is that spiritual considerations are part and parcel to every aspect of the Mlabri way of life, the physical and the spiritual worlds completely intersect for them! So you can’t say that helping someone get better physically isn’t a spiritual thing. Then I’d get it from the atheists, deists, you know, secular humanist people, they’d basically say that their culture needs to be preserved.”

“Ok, I’ll give you some things, and you tell me if you want them to be preserved,” elaborates Gene. “When we got here there was an infant mortality rate of 50%. You want to preserve that? Last year we had seven babies, all of them are still here. Is that bad? How about when they get a toothache, we’ll just let it swell up and explode like they used to, and their mouth is all full of puss. You want to preserve that?

How about citizenship, they have that now, so they get healthcare and go to school and can start a business, should we preserve them as criminals on their own land? A lot of people, they look at the Mlabri and they see picturesque poverty, and that’s what they want to preserve. Really? They say, ‘If you keep helping these people out they’re not going to be Mlabri anymore.’ The way I see it, the only thing they’re in danger of is being Mlabri.”

In 1996, the Mlabri received another visitor, a Swiss textile engineer named Peter Schmid who happened through the Mlabri village on a motorcycle tour. Schmid couldn’t help but notice the Mlabri’s skills of weaving bags from vines they found in the jungle, a bag that combined braiding, weaving, and macro met. He had heard some of the Mlabri’s story, and knew of their state of poverty, and offered a suggestion that the Mlabri should make hammocks as a means of income.

The hammocks provided a supplemental income for some Mlabri at first, most of the hammocks being sold on eBay. But initially, most of the villagers didn’t see much in return for their work.

“When we first started making hammocks we just made too many,” recounted Gene, “I was giving them away! They were spending all this time on them, and we had a guy that said he wanted to buy all of them, but then there were too many and he couldn’t afford it, so people would come up here and I’d give them a bag of like 13 hammocks, and that’s just not a good business model.”

Enter Joe Demin, an American backpacker who happened across a Mlabri woven hammock while hiking around various islands in the Andaman Sea. He was instantly smitten by its craftsmanship, to the point that he had to visit the Mlabri to see it for himself, and brought along an idea of his own.

“It’s more about giving people a job that allows them to remain together,” says Joe, founder of Yellow Leaf Hammocks. “It allows them to empower themselves, so they can drive their own change. Back in the United States people were saying things like ‘Hey, this is a village, they’re poor, let’s give them things,’ but I saw it as a beautiful opportunity. With hammock weaving we’ve seen that it has dramatically changed people’s trajectory because they had a means to an income that they were responsible for themselves.”

Yellow Leaf Hammocks is just the latest start up to market the hammocks to the United States, Mlabri work with other sites as well including jumbohammocks.com, maintained by Peter Schmid who markets the hammocks to Europe, and mlabri-hammocks.org that markets to Japan, but Joe has taken a different approach by presenting them to more high-end retailers at a higher price point, and has seen an incredible demand for the product.

The model has been used to offer Hmong and Northern Thai villagers the same opportunity and provides them with a comfortable and reliable alternative to working long, labour intensive jobs in agriculture.

Jiap, mother of three, with one more on the way, is a local Mlabri and hammock weaver. The process has become second nature for her as she manoeuvres the shuttle across a taught strand of yarn, forming another weave in a beautiful pattern of indigo and natural white.

“Weaving hammocks is fun, it’s much better than working in the fields. I don’t have to worry about the weather, I can work in the shade out of the sun, and can rest when I want to. If I didn’t have this job, I would be working in Hmong fields.”

With the income from weaving hammocks, Jiap plans on building new mice-proof rice storage. Her opinion is similar to those of others’ weaving that day, Sukanya and Pla, both of whom agree that without the hammocks, the only alternative would be working on Thai or Hmong farms.

Inside many of the cluster of houses in Ban Boonyuen weavers have set up looms in their living rooms, or leave home to work in the community weaving house. They choose the workload, when to work, and what to do with the income. Inside the weaving house the three woman work while listening to the radio, their dogs lounging around beside them while they chat and laugh amongst each other. While hammock

Pulling out of the village, waving goodbye to the children playing in the gurgling stream that divides the village, and the weavers chatting and working in the weaving house, I felt overwhelmed by what I had learned.

There were so many outside forces, so many layers, so many stories of hardship and good will simultaneously that had led the Mlabri to this point. I left them laughing and weaving, and with my vague understanding of the hardships they had gone through. Whatever the future brings to the Mlabri, whether they remain a tribe, or become assimilated into the frenetic outside world, as have so many, their fates are, at least, now in their own hands.

To support a local weaver and pick out your own Mlabri hammock, check out yellowleafhammocks.com or jumbohammock.com.