“When I first moved to Chiang Rai in the early 80s, the city’s cultural events consisted of parades blaring international and Thai pop tunes carrying along beauty queens in white tulle western style dresses on foam and plastic floats,” recalls Rebecca Weldon of her early years in the northern city.

What Rebecca is talking about are the incredible changes which have turned the ‘behind the mountain’ town of Chiang Rai into a city famed for its artistry and culture. Today, some of the greatest artists in Thailand hail from, and live in, Chiang Rai. The province itself is home to unique initiatives which have been adapted and adopted nationwide. While change has indeed come, as it tends to do, Chiang Rai has embraced its changes while infusing them with the city’s very own creative palette.

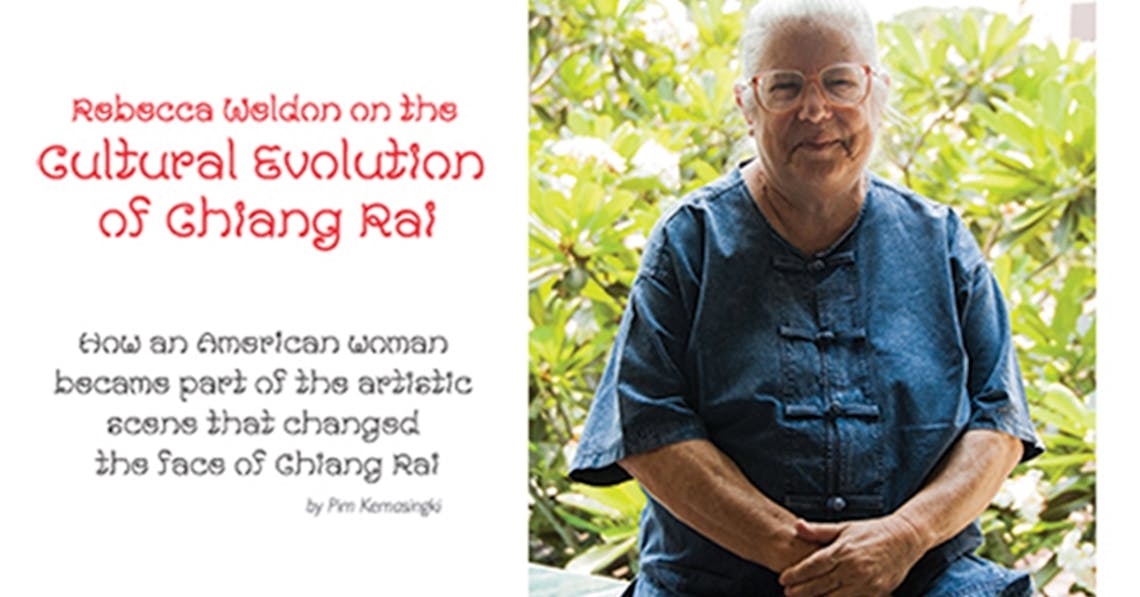

Rebecca Weldon is a familiar face to those of us who have lived here for a while. Short, plump, with a white bun atop her head, Rebecca is always seen in her ‘uniform’ of faded dark blue morhom. An unassuming woman, Rebecca says that she likes to stay unremarkable and unexceptional, but after getting to know her, one realises that her life has in fact been quite remarkable, and one of great exception.

Rebecca and her two younger brothers spent their early childhood in Louisiana before moving to Samoa in 1960, where their physician parents went to work for the US Department of Interior. Though rusty, Rebecca, who has had a lifelong love affair with languages, still speaks Samoan today…along with Laotian, Thai, Northern Thai, French and of course English.

In 1963, the Weldons moved to Vientiane, Laos, where the parents administered the public health programme for USAID. “There were only seven Laotian doctors in the whole of Laos in those days and we spent much of our time upcountry,” says Rebecca. “We did not live in the American compound. We went to a local school taught in French and we had lessons in Laotian on the weekends.”

After many years in Laos, Rebecca was sent to boarding school in Switzerland as her parents headed off to work in other countries including Egypt and Haiti. Rebecca continued her studies in Belgium, Paris and California, graduating with a BA in anthropology. She worked in Haiti for awhile before returning to Southeast Asia in 1981. This time, because of conflicts in Laos, her destination was Thailand, where Rebecca spent a year in Nong Khai working for the Catholic Relief Services.

It was in the early 80s when Rebecca met her Thai husband, Julaphan Sithiwong, who worked for Thai International, and moved to his hometown of Chiang Rai. There she helped him set up the first Chiang Rai based tour company, a guesthouse and the first western restaurant in the city, the Golden Triangle Cafe and Inn.

Rebecca’s cafe became the meeting place for those who would eventually reshape Chiang Rai’s landscape. People like great writer and bon vivant Rong Wongsawan, who had a house in Chiang Rai; local legend and arguably Thailand’s most famous living artist Thawan Duchanee; cultural provocateur Nakorn Pongnoi, one of the founders of the Mae Fah Luang Foundation; Wicha Promyong, founder of Doi Chang Coffee; and ceramist Somluk Pantiboon were amongst her customers and friends.

A decade later, when Rebecca opened up Chiang Rai’s first art space, Ahimsa Gallery, the next generation of influential artists became supporters, including Chalermchai Kositpipat of White Temple fame, who exhibited at her gallery in the early years. Internationally acclaimed artist Angkrit Ajchariyasophon used to spend hours sitting in her gallery as a young student, looking at paintings and reading art books. Ahimsa was his only true contact with real art in those early days. Today, Angrit spends his life travelling around the world, exhibiting at such prestigious events as the Venice Biennale.

It was one of those rare moments in time when the right people came together at the right time.

“Chiang Rai was ready for change at that time,” continues Rebecca. “The border conflicts were over, many Thais who had gone to study elsewhere were returning, the expat community was developing, businesses were beginning to take off, trade was roaring between the now opened borders and tourism was arriving. For the pioneers of Chiang Rai, this was the perfect time. They were all looking for something to do, places to go and people to meet. The early eighties was a time of great possibility and with the right people, those possibilities became realities.”

At the Rai Mae Fah Luang, cultural events spearheaded by the students and Nakorn were put on and artefacts were bought or donated to enhance these events. Soon these objects became collections and over the years the collections grew larger and larger (with Rebecca’s guidance, the collections eventually turned into a museum) while the small cultural events eventually birthed the mega Wai Sa Mae Fah Luang annual festival in the early 80s. Wai Sa Mae Fah Luang saw hundreds if not thousands of Bangkok and Chiang Mai socialites attend. Ladies with double-decker hairdos and double-deep pockets came to parade their jewellery while their husbands rubbed shoulders with Royal sponsors. These Bangkok elite were utterly charmed by the cultural extravaganza of the event and the foundation received generous donations to continue its work.

“Rai Mae Fah Luang hit Thai consciousness at a time when people were concerned about changes affected by the economic successes of Thailand,” explains Rebecca. “When Bangkok grew in the late 70s and early 80s, Thai people looked to the west for all things. It reminded me of when immigrants arrived in the US and discarded their cultural roots, seeking to shed their Polish, Russian or Bulgarian pasts. Those in Bangkok were looking to the west for cultural influence while the rest of Thailand was looking to Bangkok. Within two generations, Northern Thailand’s strong and illustrious literature was obsolete, its language only preserved in spoken, not written, form. Similarly, Thai artists were emulating western artists and much of what was Thai, artistically and culturally, began to fall between the cracks through sheer lack of support. But this unique group of artists living in Chiang Rai bucked the trend. Thawan was rejected as an artist for many years because he didn’t follow them. He created Thai art at a time when others were doing western influenced impressionist or abstract art.”

Today, Thawan, Angkrit and Chalermchai can pretty much set any price for their works: Thawan famously sold a painting for twenty million baht, Angkrit commands over 150,000 at least for one painting, and Chalermchai is involved in mega projects worth hundreds of millions, his own paintings going for up to six million a peice.

“But in the early 80s, when Wai Sa Mae Fah Luang came about, Thai people were feeling the effects of internalising their culture. People felt Thai, but they didn’t show it on the outside. They wanted to join the modern world and were proud of being as western as any westerner. This was promoted by the government as the roadmap toward success and acceptance. Unlike neighbouring countries, Thailand didn’t have to fight a colonial power in order to preserve its culture; it perhaps therefore let it go more easily. It was only as the economic successes of Thailand created these sweeping changes that Thais realised they must start fighting to preserve their culture. The 60s and 70s saw foreigners like Jim Thompson acting as custodians of Thai culture, and Thai people began to feel as though they had lost something. As the antique trade sucked artefacts out of the Kingdom, those in Bangkok took stock and began to appreciate all things Thai. Artisans were patronised by rich Bangkok socialites trying to go back to their roots, renovating temples and designing government buildings. Historians started to do research into a variety of fields in the search for authenticity, and the government’s patronisation of tourism created the momentum to support Thai culture.” In other words, art flourished.

In Chiang Rai, Rebecca was part of this massive shift in consciousness. She had joined her friends in the art community as a volunteer at Rai Mae Fah Luang shortly after her arrival in Chiang Rai in 1984, and by 2002, after she had continued her studies in Museology in the Netherlands (at the age of 50), served as curator at Rai Mae Fah Luang, which had been renamed the Mae Fah Luang Art and Cultural Park.

Rebecca shares the visions of HRH the Princess Mother and Nakorn. “I believe that every human being is born with a specific and unique talent and that is what makes us so unique as a species,” she says. “We grow up differently, we think differently, but yet we all have something to offer. It is important to support individual talent in whatever form, and this is how the Mae Fah Luang Foundation started. Visionaries like Thawan, Nakorn, Vithi [Phanichphant, Chiang Mai historian and custodian of Lanna culture] laid the foundations and evaluations for our future. I don’t think of them in terms of people who preserve the past, but as people who give meaning to the present so that we can evaluate where we want to go in the future. For instance, when you think of Nakorn, you associate him with tradition, when in fact he is a very contemporary man who supports contemporary writers and poets. He is not a traditionalist by any means.”

Because these people stepped up at a time when leadership was needed, and their passion and knowledge makes them undisputed experts in their various fields, they are today considered cultural arbiters, looked up to by the generations of students that follow and consulted by all sectors, from academia through government and private sectors, for their knowledge of Lanna culture. While they have significantly helped to regenerate the concept of Lanna culture, they freely admit that their representation of arts, crafts, dance and traditions are modern interpretations, not faithful replicas of the past.

So how did Chiang Rai evolve so successfully?

“I don’t think that Chiang Rai is more artistic than anywhere else in Thailand,” she explains. “What has become iconic about Chiang Rai is that the artists are not lost in the development. In other words, while Chiang Mai has more artists than Chiang Rai, they get lost in the jungle of the city. In Chiang Rai, Thawan moved away from his mother’s house near the Wang Come hotel to open an art park on his land ten minutes out of town; Chalermchai and Somluck also moved out of town. People therefore go to these artists as a destination, making them visible and constantly relevant. These individuals are so respected and admired by the people of Chiang Rai, who are proud of their successes, that they also found themselves influencing change. People identify with the artists and this makes art significant to the people of Chiang Rai. Their leadership also helped Chiang Rai to avoid some of the tourism and development mistakes Chiang Mai made, so the art in Chiang Rai has not become eclipsed by development.”

Another interesting point Rebecca brought up is that many of Chiang Mai’s artists are affiliated with the Faculty of Fine Arts, Chiang Mai University, earning their living as lecturers. In Chiang Rai, artists need to sell their art to survive. This has helped force them to either create sellable art or become theoretically advanced enough to get oversees grants.

“In Chiang Mai”, adds Rebecca, “the artists who make a living solely off their work seem to be those in the Night Bazaar!” she jokes.

Following her husband’s death and the death of one of her two sons (she also has one daughter who is studying in Chiang Mai), Rebecca turned over the museum operations to the local staff in 2008 and returned to serving as a volunteer museologist and docent. She has now moved to Chiang Mai, and is looking forward to getting involved with new projects in this city. In a few short months she has already been appointed convener of the Informal Northern Thai Group, relishing the opportunity to connect with academics and researchers from around the world who pass through Chiang Mai, sharing, debating and learning about a variety of topics. She is also currently helping to set up the Prince Mahidol Museum opposite McCormick Hospital, which will be a historic house project, her specialty being in working with religious and sacred artefacts. Her work with sacred artefacts of all religions has only strengthened her faith in Catholocism.

Settling into her new life in the big city of Chiang Mai (compared to Chiang Rai, that is), Rebecca has found friendship and satisfaction by joining the Writers Without Borders group, about twenty writers of all genres who come together once a week to give critiques to one another. The group has been giving her feedback on the memoirs she is currently writing.

It is a big adjustment, moving to Chiang Mai after so many decades in Chiang Rai. But Rebecca is up to the challenge. She intends to get involved, work on projects to give back to the city, spend time with her daughter, catch up with old friends and hopefully find herself a new place she can call home.