Architecturally, it’s almost as though there are two Chiang Mais: the hideous suburban sprawl, with its ubiquitous cookie clutter moo baans, malls and condos which adorn the various ring-roads circling our city, and the creative and stylish twists to contemporary Lanna aesthetics found in hotels, spas and cafes in the old city and outlying communities.

“In Chiang Mai, the tourism industry is the hero,” agreed Apichart Sri-arun, lecturer at Rajamangala University of Technology Lanna, “this has been a gift in that many business owners want to offer local flavour to their guests, and this has meant that owners support architects who wish to infuse their projects with the Lanna identity. When I first started working as an architect over thirty years ago we either built generic buildings which could have been seen anywhere in the world because we thought that was how hotels, banks and commercial buildings had to be to suit modern lifestyles, or we would build very traditional Lanna architecture for clients who wanted something local. There was nothing in between.”

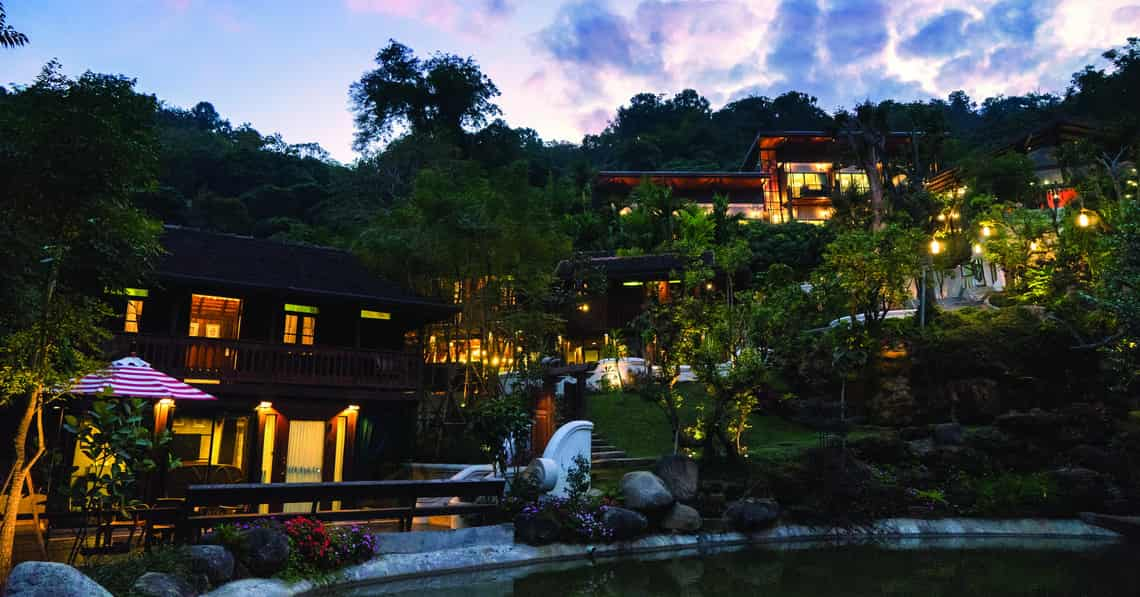

Pawat Tantayanusorn of Niwat Architects, agrees, “When my father first started forty years ago, Lanna architecture was seen as something to faithfully replicate, not to interpret. Anyone attempting to build anything Lanna had to study traditional architecture, looking at old rice barns, houses and temples, and copy the methods, features, materials and functionality to a tee. It is only recently that architects are really experimenting and pushing boundaries, and the results are what you see now, some very impressive buildings. Just drive around the old moat and look at some of the new boutique hotels like Makka or Makka Chiva, both beautifully designed and very Lanna in mood and style, but also modern in function.”

The doyen of Chiang Mai architecture, Ajarn Chulathat Kitibutre, most well-known for his work on the stunning Four Seasons Resort Chiang Mai as well as being the architect and owner of Baan Suan Restaurant and Residence explained, “When modern lifestyles changed, architecture had to change to accommodate it. No one wants to sit on the floor and eat kantoke style or live in an open-aired home with no air-conditioning, so many architects adapted. But whereas in the past we simply lifted ideas from the west and plonked them here, architects today are now doing their research, studying the past, because it’s only when you know where you are coming from can you truly move forward.”

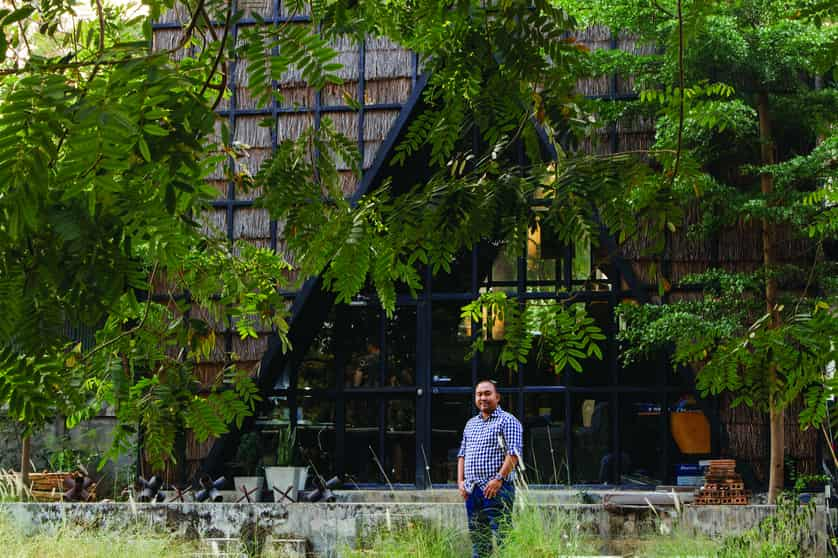

Mae Kaning Creative office designed by architect Ronnachai Khanpanya

“I get asked all the time what Lanna architecture is,” he laughed. “It is simply organic. It’s natural and cultural and is open to so much interpretation. Sure, there are purists out there and there is a place for everything, but you can’t force young architects to simply replicate, they will simply reject. Tastes change and we must allow for flexibility.”

“Much credit has got to be given to the municipality which, since 1979 has set increasingly strict and stringently enforced guidelines for the construction of buildings in the moated city,” explained Apichart. “Whereas Bali restricts buildings to the height of coconut trees, ours was set at 12 metres which was the average height of many pagodas and temples. There are laws governing paint colours for building facades, roof designs which must conform to Lanna style and other details such as materials used. While this has caused many problems for architects, it has resulted in the change you are seeing today. Initially architects simply slapped a traditional kalae atop a gabled roof and called it Lanna, but things have changed and we are rising to the challenge. The government tells you to make something Lanna, and they may have kantoke dinners and kalae rooftops in mind, but a young architect who doesn’t want to be told what to do may instead say that for him, songtaews are Lanna. Is he wrong? No. They are both Lanna and they are both right.

After all, what is Lanna? Is it glittery temples, rustic rural wooden houses, colonial era mansions or hill tribe aesthetics? Today you can see that architects are drawing from all of these traditions and more and doing an excellent job at it. The selling point of Lanna is this collectiveness which has the taste and function to lead to sales and success.”

The Wall on Huay Kaew Road, like Nimman One, drawing inspiration from the bricks of the old city moat

“There are a lot of pearls amongst the bulls*$t here,” agrees Markus Roselieb of Chiang Mai Life Construction, probably most well known locally for designing the award-winning Panyaden International School, built primarily with bamboo and earth. “Chiang Mai is like Ubud with its deep cultural roots which attract people of quality. One of the best architecture firms in Thailand, A49 has a second office here and it is because they see many interesting features here which they can work with and create off. Some places have nothing; they are empty. But Chiang Mai has an identity, a soul which allows for liberal interpretation. Nature, climate and culture come together to offer a clear direction and the vibe of the city pushes you to dig a little deeper, not just filling a space. As an architect, if you have even a little amount of sensitivity, Chiang Mai will tell you what to do. It will knock you on your head.”

“In the past a designer would have to spend years creating a portfolio in order to achieve recognition,” added Pawat. “Today a young designer with a small budget can focus on one feature — perhaps a wall, a doorway, a staircase — and with one perfect shot on Instagram, can become known globally. This is a huge power and it means that many young designers push themselves further and further to be recognised and this is wonderful for creativity.”

One such young designer catapulted to fame when he co-designed a small prefab thatched A-frame café in Soi Wat Umong which went viral on social media for its low-cost construction, ability to be transported to a new location and use of natural and recyclable local materials.

“While I am from here, I never felt any great loyalty to the past,” explained Ronnachai Khanpanya of Mae Kaning Creative, “though of course I appreciate elements of it. I think that the laws imposed on us is a good thing because no building stands alone, it is always a part of a landscape. I get excited with using local materials in interesting and new ways and thinking outside set limitations. For instance, the only reason the café was able to be dissembled and moved was because our landlord only signed short-term leases, so we had to find a solution. My office which we built a few years ago behind the café uses traditional thatch, not just as a roof, but also as walls, so that generated a lot of buzz and was very well received by the architectural world. I see more creativity in public spaces such as cafes and hotels where people can go in and really breathe in the ambiance and many of my peers are finding opportunities to get very creative. Of course most of the big projects with massive budgets are probably still going to Bangkok architects, like the latest One Nimman building, but in a way big projects limit creativity because function is so very important. With something small, you can really focus on form and that gives you a great opportunity to be discovered when you are just starting out.”

So why is the other Chiang Mai, the ugly one, still metastasising?

“Did you know that Ajarn Chulathat once said that his life’s ambition was to build a condo which was Lanna?” smiled Sant. “He hasn’t quite got round to it yet unfortunately and as far as I know no one has.”

“The real estate gang,” Sant continued, referring to the large property developers who are building the aforementioned moo baans and condos, “are selling a romanticised version of life. You have the grand entrance with a boulevard which harks back to the 1950s America where the dream was to have wealth, private driveways, a husband slowing down his car as he loosens his tie, his wife in an apron and two children greeting him with a martini. They are peddling executive exclusivity and a promise of an elevation of life’s prospects. And as you can see, this dream sells. These projects are easy to build, easy to get a stamp of approval and easy to sell. Everything is pre-selected so that the buyer doesn’t have to think, all they have to do is move in.”

Roselieb says that he wouldn’t consider his designs Lanna in any traditional sense, but because it is now acceptable to interpret Lanna aesthetics, his use of space, air flow and materials would likely put him in that category. “I don’t want to use a fixed phrase to describe what I do because even if I am considered Lanna, I am not at the centre, but on the fringes.”

“That’s perfectly OK,” agreed Ajarn Chulathat, adding that as long as a building inspires and looks right in its setting, using local materials or ideas, then it could very well fall into what is now being called contemporary Lanna design.

There are some aesthetics which are distinctive enough to be globally recognised, the obvious recent and neighbourly success story being Bali designs. Does Chiang Mai have what it takes to put a stamp on Lanna aesthetics, and perhaps one day even export it to the world?

Tasteful modern Lanna design of the new Chiangmai Ram Health Centre

“We are definitely not there yet,” said Sant who echoes Ajarn Chulathat. “Many young architects are still rebelling and looking to the west for ideas, whether they are suitable to this location or not. What they must learn is that you need to know what you are escaping from to know where you are heading. Otherwise you are just the peel, not the substance.”

“We have already begun the journey,” ended Ajarn Chulathat, “but I think it will be at least another decade when we can truly say that Chiang Mai architecture has formed a strong and instantly recognisable identity.”

Tasteful modern Lanna design of the new Chiangmai Ram Health Centre

“We are definitely not there yet,” said Sant who echoes Ajarn Chulathat. “Many young architects are still rebelling and looking to the west for ideas, whether they are suitable to this location or not. What they must learn is that you need to know what you are escaping from to know where you are heading. Otherwise you are just the peel, not the substance.”

“We have already begun the journey,” ended Ajarn Chulathat, “but I think it will be at least another decade when we can truly say that Chiang Mai architecture has formed a strong and instantly recognisable identity.”