Journalists in French Indochina (Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia) have since the beginning of investigative – or even controversial – journalism in their countries been constrained by the limitations imposed upon them by dictatorial governments and the threat of venal public officials. Exponents of free speech and human rights are continually being incarcerated all over Indochina and Mainland South East Asia (also sometimes called Indochina but including Thailand, Burma, Malaysia and Singapore), while censorship, sometimes undertaken by exterior official sources, and/or self-administered, is a regularity that is intractable in most forms of media. Writers and editors risk imprisonment if their criticism falls within the rubric of what their governments hold is a ‘threat to national security’, which at times can be a very lean charge. Even with (or perhaps because of) the vast improvements in technology, and its circulation and consumption, the freedom of press throughout Indochina is still, according to various media NGOs, of the most restrictive in the world.

The Vietnamese media is state owned, and although much more than a political mouthpiece, it is still verily controlled by the government, diligently censored, and in some forms a prime dispenser of The Party’s raison d’ètre. Journalists in Vietnam do push the envelope, though there can be dire consequences – while there are also topics, as there are here in Thailand, that no journalist would dare go near. Calling for democracy, for instance, is absolutely verboten in the mainstream press, as is critical analysis of the education system. Critical theory can, and does, go underground, though dissident bloggers write at their own peril. Cu Huy Ha Vu, a blogger and activist was sentenced to seven years in April for allegedly subverting the government and calling for a multi-party political system.

Many social network sites are blocked (though not acknowledged by the government), including Facebook, but it doesn’t take an IT savant to get around ministerial prophylaxes. The government does occasionally squeeze out its own social networking sites but social ID numbers are required. Vietnam is often said to be a very IT strong country, as well as being a nation where reading is considered a requisite pastime, compared to the other Indochinese countries. Combined, this has developed the country’s media; nonetheless, there have been a spate of arrests and sentencings in Vietnam over the last few years of editors and reporters, as well as gagging orders on stories, and websites that have gone up in puffs of red smoke.

In March this year Bridget O’Flaherty wrote in the The Diplomat (international current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific region) in an article entitled ‘Vietnam’s Murky Media Picture’ that “a new press law came into effect that introduces fines for reporters for vaguely defined infractions, and obliges them to publish their sources.” This kind of governmental stricture will of course inhibit the integrity of any journalist’s work in Vietnam, though O’Flaherty writes that in spite of this the “Thanh Nien News and Tuoi Tre (both owned by youth organisations a couple of steps removed from the Communist Party proper) often contain thoroughly investigated stories about environmental issues – and sometimes even corruption.”

Popular outspoken VietnamNet editor Nguyen Anh Tuan was permitted by the Ministry of Information and Communications to resign in March this year. Afterwards he refused to comment on his resignation. “His dismissal,” writes “O’Flaherty “was allegedly so he could take up a less ‘contentious’ government post, and is said to have been on the cards since late last year, largely over the paper’s reporting on sensitive issues.”

Editors must always be cautious in Vietnam. An example of governmental tough-love handling of the media that made world news was in 2000 when the chief editor of Vietnam’s largest newspaper, Tuoi Tre, was fired. All the copies of the newspaper were also pulled from newsstands and burned. The offending article had concluded after a reader survey that Bill Gates was more popular than Ho Chi Minh with the city’s youths.

Reporters without Borders (RWB) wrote in an article, also in March this year, that Vietnamese underground poet/writer and founder of Giay Vun publishing house, Bui Chat, was arrested by Vietnamese authorities just after he had “returned from Buenos Aires, where he had received the Freedom to Publish Prize from the International Publishers Association (IPA).” RWB writes “The Vietnamese authorities gave no reason for Chat’s arrest but it seems directly linked to the prize he received…Although Vietnam claims to have made significant progress on human rights, journalists, netizens and now publishers continue to be jailed if they dare to defy the government by voicing or relaying dissident views.”

The international press in Vietnam has more freedom than the local press, as is the case in some other South East Asian countries. Prepublication censorship is undertaken by government officials – not always with editorial adroitness, one journalist working in Vietnam told Citylife – in some local newspapers and magazines. Even the censoring process, Citylife was told, is veiled in secrecy. Foreign journalists however, just as Thais have done for decades, use euphemisms to get past the clumsy hands of the text extractor.

The Vietnamese press regularly exposes lower level corruption. Though cynically, a media source in the country told Citylife, that maintaining a regular public name and shame of corrupt rural officials is often just a maneuver that consolidates The Party’s legitimacy. Meanwhile a major story such as the PMU18 scandal where millions of dollars of aid money was allegedly gambled away became taboo in the Vietnamese media, soon replaced by the usual proxy tales constructed of less politically hazardous material. A report by Oxford Analytica on media in Vietnam states that “editors were also sacked and reporters sent to jail” over the PMU18 scandal. The report reminds us that newspaper editors in Vietnam are “servants not just of the state, but of its public security sector.” Do Quy Doan, the government’s deputy minister of information and communication announced that journalists had distorted the truth and exaggerated, and that there was no political motive in the decision to arrest them. Notwithstanding, the reports were cogent enough to force the transport minister and his deputy to resign. Editors, says the Oxford Analytica report, must be constantly aware of the “no-go zones” and never critical of the flaws in the political system.

David Brown, a retired US diplomat and long time observer of contemporary Vietnam, writes in an article ‘A Fiery Silence in Vietnam’, of the fate of Le Hoang Hung, who was murdered January 19th this year. “Hung covered family squabbles, neighbourhood disputes, suspicious deaths and disappearances, arrests of gamblers, smugglers and dope dealers, and complaints about police brutality and wayward officials.” Browns goes on to say that, “Hung was hardly a radical; he was a Communist Party member, a former non commissioned officer in the Vietnamese Army, and the son of a Vietcong soldier.” Though many thought the errant journalist must have overstepped the line when he reported about corruption involving senior officials.

“Reporters and editors have learned which subjects or situations they can cover boldly, which conflicts may only be hinted at, and which are forbidden,” writes Brown. Hung, who was doused with gasoline and set on fire in his bed, caused many journalists in Vietnam to panic. Though in the midst of the widespread mediaparanoia Hung’s wife confessed to his murder. The case has since become a matter of controversy. “Whether it’s a chilling tale of press repression or simply a sordid domestic scandal, the circumstances of his death are the sort of story Hung would have likely pursued with vigor,” says Brown.

As a result of Vietnam’s limitations on media the country’s blogging industry has naturally evolved creating an au courant strain of headache for the government. While a fraction of Vietnam’s internet savvy population have been quietly tapping out their thoughts in cyber-space, under the scrutiny of the government’s omnipresent eyes, the country has also adopted a rich blocking industry. Geoffrey Caine, a Fulbright scholar researching mass media in Vietnam explained to Citylife: “In short, bloggers’ freedoms in Vietnam have taken a dive in the past 3-4 years. Unlike in Thailand, where most arrests are on the grounds of lése-majestè against the monarchy, here most bloggers are jailed or harassed for challenging the authority of the Communist Party. The government usually asserts questionably worded charges such as undermining national security and social harmony, and defaming the honour of state leaders.” He adds that the crackdowns were particularly far-reaching leading up to, and during, the 11th Communist Party congress last January, an event every five years when party delegates elect the new cadre of leaders. “This is a particularly sensitive time that they fear dissidents can take advantage. The Arab Spring and North African revolutions have also added to the press and blogging crackdown.”

“There is a dark face to Laos that no one talks about,” a representative for a former media NGO told Citylife. After Burma, Laos has South East Asia’s worst track record of free speech in the press. It’s a country that is enveloped by secrets, hardly visible to the outside world, and where very few people have access to the internet. Only 30% of households have a TV, and newspapers reach less than a quarter of the population, says a 2009 report called Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific. “Laos is one of the most ethnically diverse countries in the region and is ruled by an iron fist by the centrally located Communist Government,” said the NGO source, explaining that print media is so small that it is virtually non-existent outside Vientiane. “In rural areas,” she explains, “the print media consists largely of government broadsheets published by the Ministry of Culture.”

The organisation, that spent almost a decade training journalists in South East Asia in radio, print and television, explained that the problem in training journalists was that upon return to their countries the journalists were often not allowed to implement what they had learned due to government strictures on the freedom of press. “Everyone,” she explained, “of any position of note is in the Communist Party.” This virtually ensures that criticism of the political regime is unheard of. “There is a definite ceiling which you can’t get through, when it comes to news which affects senior officials,” the anonymous source said.

“In Vietnam journalists always had minders taken everywhere they went, and until six or seven years ago among each group of journalists attending our courses, at least one would have been delegated the job of ‘minder’.” she said, and added that even though the NGO was mostly allowed to interview and screen journalists for quality and interest, “in Laos the pool of journalists from which to choose candidates for journalism training was very small, and most, but not all, followed the party line to letter.”

Another problem they faced was that each journalist came “with baggage”, a feeling of superiority due to their nationality and in-built cultural prejudices. “The Thais looked down on everyone, the Cambodians had visceral hatred towards the Vietnamese, the Vietnamese looked down on the Cambodians and were wary of the Laotians and the Thais, and the Laotians had a strong love/hate relationship with the Thais.” Though in spite of this, after time journalists responded well to programmes and were mostly “invigorated by what they learned.” Many of the trainees, she said, are now editors all over South East Asia.

One Laos based travel writer told Citylife that, “The Vientiane Times is more like the social pages showing how the government is progressing on various development projects. You will rarely read or hear anything negative about the government in the Laos media.” He explained that if there’s a social or environmental issue that needs to be addressed, the media will report it, but “in a face-saving way.”

“I’ve recently written on the Mekong dam issue,” he says in support of some freedom of press, “and how neighbouring countries are against it.” On censorship he says, “I’ve been based in Laos for four years and have never submitted anything I’ve written to a government agency until after it has been published.” Although he does add that there are certain matters he just wouldn’t pry too deeply into.

The Press Freedom Index published by Reporters without Borders writes that Cambodia is considered to be the only country that has a ‘partly free’ press in Indochina. Incidentally, Indochina’s close neighbour, Thailand, was just relegated from ‘partly free’ to ‘not free’ this year. In spite of Cambodia’s better standing they have the highest official number (9) of murdered journalists since 1992 according to the New York based Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Jeremy Wagstaff, a journalist, consultant and researcher who has worked for the BBC, Wall Street Journal and Far Eastern Review wrote in a 2010 study on South East Asia press freedom entitled South East Asian: Patterns of Production and Consumption, “Most media in Cambodia are private but affiliated in some way with a political party. Most media outlets are not owned directly by politicians, but by private citizens, albeit with a political agenda. So while there is no government censorship, partisan influence leads to strongly biased news coverage.”

The study shows that two thirds of households have no TV in Cambodia, and states that most channels are “strongly under the influence of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP).” Radio, writes Wagstaff, is by far the most prevalent form of media in Cambodia, but radio too, he adds is “considered to be under CPP influence.” An independent popular channel called Radio Beehive, which is the most popular channel in the country, has twice seen its owner Mam Sonando jailed.

Wagsaff’s report tells us that only 1 per cent of Cambodians use print as their primary source of information. He writes, “In part this is because of high illiteracy rates – only 67.7 per cent of adults are literate, according to UNESCO.” And many newspapers are run by political parties or individual politicians; only the foreign language newspapers are considered to be free of overt political influence, writes Wagstaff.

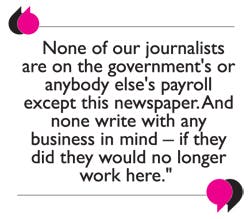

Alan Parkhouse, the present editor of the Phnom Penh Post and formerly an employee of The Nation and Bangkok Post told Citylife that he will tackle any kind of issue and he and his staff face no prepublication censorship by the government. Parkhouse informs us that “None of our journalists are on the government’s or anybody else’s payroll except this newspaper. And none write with any business in mind – if they did they would no longer work here.” He expands by saying that no one as yet who works for him has been imprisoned for their criticisms, which are often of a political nature. “But we make sure of our facts and we get very few complaints from the government. Basically, they leave us alone.”

On Cambodia’s murdered journalists (who’d mostly exposed local and official corruption) Parkhouse explains that his newspaper often writes about corruption but with the utmost care and fastidious fact-checking. “We have had no trouble,” he says.

The world of blogging and social-networking is yet to saturate Cambodia, though the government is already discussing how to censor the ‘net appropriately. South East Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) reports of a plan by the Cambodian government to regulate the internet through various laws. Journalists and NGOs have already voiced concerns about strict government regulations, but it seems when the majority of the nation is ready for the internet the government intends to be equally ready for the inevitable fall-out with its citizens.

May 3rd was World Press Freedom Day. It was the day Freedom House, the US-based think-tank, announced the decline of press freedom in some parts of the world, with Thailand being pointed out as a country the organisation is particularly worried about after reaching its lowest ever rating. During April and May activists and opposition journalists were arrested in Thailand on lése-majestè charges, while radio stations were forced to close. Also in April Thammasart historian Somsak Jeamteerasakul along with other academics, human rights activists, and journalists released statements calling for the protection of freedom of speech after they alleged threats had been made to them. Somsak currently faces charges of lése-majestè filed by the Royal Thai Army in May. Shortly after The Nation wrote an editorial lamenting the decline of free media, and the Bangkok Post ran a story on May 4th about the ‘decline’. Media representatives have since met with Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva about media reform, and contrary to Thailand dropping through the rankings from a ‘partly free’ nation to a ‘not free’ nation since Abhisit’s tenure, Asia News Network (ANN) reported that the PM “deplored that fact that in the past decade press freedom has eroded in Thailand”…

This part of the world, yet to be comprehensively whacked by the heavy arm of the internet, surely will be soon enough. It’s not unforeseeable that more of South East Asia’s future netizens will become more politically active and perhaps more discerning about what they believe due to the breadth and dizzying depths of online information. Against a backdrop of Sisyphean blocking endeavours, cyber-crimes revisions and vague arrests, it seems alternative news still remains indefatigable. Perhaps more Indochinese governments and their policies may be shaped in the future by growing numbers of online underground citizen journalists whose views are hardly congruent with the dictatorships they were born in – kind of a role reversal of the ‘chilling effect’.

Wagstaff writes in his study of an imminent ‘terror alert’ to dictatorial governments: “With the possible exception of Laos, journalists, bloggers and media practitioners have found ways to circumvent restrictions on news reporting, intimidation and censorship in all the countries surveyed here [South East Asia]. From the anonymous stringers feeding stories to Burma’s Mizzima and Irrawaddy to the bloggers of Vietnam, news finds a way out, whether the restrictions are technological, legal or physical. Indeed, in some countries traditional media are in danger of becoming irrelevant as political debate, the exchange of views and dissident voices go online.”

——————————————————————————————————-

Much of the information in this article was supplied by journalists who asked to remain anonymous.