Barricades in the street, hiding in homemade underground shelters, listening to the screams and cries of his terrified neighbours: ‘The military is coming! Go, go, go, go!’. For many, this sounds like something pulled from our worst nightmares. For Tun, this was his childhood. Tun was born and raised in Hlaing Bwe Township in the Kayin State of Myanmar (Burma) during the late 1980s. Tun remembers the harrowing details of his experience growing up in Myanmar, his village living in fear of the Burmese military.

“We were always afraid.” Tun recalled, “‘What’s happening tonight?’ [we would think,] ‘Tonight will the military come in and take the people…?’”

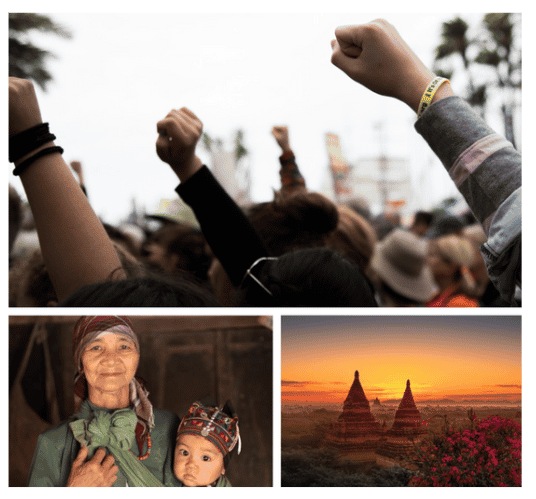

Unrest in Burma has persisted since the nation’s independence from Great Britain in 1948. The conflict began between the country’s multiple ethnic groups, minorities fighting to retain their religious and cultural autonomy from the capital. In the name of unifying Myanmar, the military led their first coup in 1962. The power and brutality of the Burmese military only escalated, leading to growing resistance from citizens, Buddhist monks, and students all across the country. In the late summer of 1988, the military initiated a strict crackdown on peaceful protesting, shooting down thousands of activists in the streets and arresting thousands more.

In 1988, Tun was a child in Hlaing Bwe he witnessed the Burmese military frequently marching on his village. What they required from the Kayin state were male ‘volunteers’ to carry military gear, artillery, and supplies to their base nearby. On multiple occasions the military would roll in on their trucks and take unsuspecting men from their streets and homes, forcing them to participate in their march. Eight-year-old Tun remembers what his parents would tell him while hiding him in their home during these invasions: “‘Stay inside, don’t cry, don’t make a sound…’”.

During one of these invasions, the soldiers found Tun’s father and took him from their village. His father was forced to walk over 20 kilometres with other ‘volunteers’ from a variety of Burmese states to their base, carrying heavy weapons on his back the entire time. Tun’s father was lucky to survive the trek and be released; others weren’t so lucky.

“My mother told me a lot of people died along the way.” Tun said, “They didn’t give them any food or water. That’s why the people were very tired…they would lay down on the ground and some people would die.”

Eventually, the military had to get creative with their ‘recruitment’ methods, as Hlaing Bwe villagers would become more clever in means of hiding from the invading soldiers. One of these methods, Tun remembers, included taking the local cinema hostage. Tun’s sisters told him about the event,

“The military locked down the cinema. The women and children [were let] go… but they wanted the men for volunteering, to carry their things.”

Tun heard stories of other villages in the Kayin state who suffered similar intimidation from the military. Many recounts describe military leaders’ brutal tactics going far beyond forcing manual labour upon villagers, including pillaging, rape, and various forms of torture to obtain information and establish dominance.

After graduating from university in 2010, Tun immediately went looking for work but had no employment prospects in Myanmar. He then made the decision to move to Thailand in hopes of better opportunities. Today, Tun has been a member of the Chiang Mai community for 11 years. He remains in touch with his friends back in Myanmar, where the state of the country has only gotten worse.

The most recent political upheaval in Myanmar came in early 2021 after the general election. The democratic party, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, won the national vote by a landslide. Burmese military leaders supported the political opposition and immediately questioned the legitimacy of the vote and the constitutional legality of Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership. According to the constitution of Myanmar, one cannot hold office if their children are not Burmese citizens; Aung San Suu Kyi son’s had British citizenship. Rumors were quickly spread by military supporters deeming the vote fraudulent, going as far as to claim about 13 million votes were falsified. These allegations of fraud have been denied by the EU, ANFREL (Asian Network for Free Elections), and PACE (People’s Alliance for Credible Elections) who verified the election’s vote collection and deemed it legitimate. Under the rule of General Min Aung Hlaing, the military once again seized control of the country on February 1st of 2021.

Civil unrest has only become more chaotic since the February coup. Protests have erupted all over the nation, initially peaceful but now more citizens are responding to military intervention with reciprocated force since the fatal shooting of a 19-year-old protestor, the first civilian death since the latest coup. Since February of 2021, arrests and fatalities due to the Burmese military’s response have only skyrocketed; according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP) as of July 13th more than 14,000 citizens have been arrested and over 2,000 killed.

David Mathieson is an independent analyst on conflict, human rights, and humanitarianism who researched the political chaos on the ground in Myanmar for seven years. According to Mathieson, the civil war has reached new heights in its severity, the worst it’s been since Myanmar’s independence over 70 years ago.

“People could live in Rangoon and not know there were wars going on. You’d have to go looking for it.” Mathieson said, “Now it’s everywhere… This is planes dropping bombs from the air, this is big guns just flattening villages.”

The nations like the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have implemented sanctions on Myanmar with varying levels of success. Attention from both world leaders and the media for the world’s longest ongoing civil war falls short in comparison to other crises such as Ukraine; Google Search hits on the war in Ukraine outnumber Myanmar over six times.

“Look at all the help that Ukraine is getting: weapons from the Germans, the Swedes, the British. If the Burmese resistance had just a fraction of those weapons…” Mathieson said.

The only chance Myanmar has for peace would require the removal of the military in its current form. Internal resistance groups or People’s Defence Forces (PDFs) have slowly been making progress in their fight against the corrupt military. The Arakan Army, for example, has proven itself to be a strong contender against the Burmese military. Their guerrilla tactics have sowed significant numbers of enemy casualties while exponentially growing in support both locally and internationally.

It remains unclear what the future looks like for Burmese citizens as they continue the decades-long fight or desperately attempt to flee the country. As for Tun, he greatly misses Myanmar and awaits the day peace will finally find his home country.

Disclaimer: The name of the subject “Tun” has been altered to protect the identity of the individual interviewed.