The fish comes hissing to my table. Its freshly grilled scales sizzle against the aluminum foil it’s wrapped in. Steam curls from its eyes, its fins. Before piercing its skin with a spoon, the young woman who brought it to my table tells me in Thai that it came from the river behind her home, the same river from which comes all the fish she cooks in her small food stand with the bamboo shoot roof and tin cups on the side of the highway. She smiles and I smile and I say thank you, finding my Thai insufficient to describe how much I am enjoying the smells of the food she has set before me: the large silver fish, a plate of som tam in fermented fish sauce, small baskets of sticky rice, a plate of mixed pak to cut the spiciness. She retreats, breaking into the local dialect to speak with another customer. I take a swig from my large bottle of Chang and eat the first bite of white meat scooped from the belly of the fish. The young woman sees me do so and asks, Saab baw? (Is it tasty?) to which I reply, as I always reply, Saab ih lee! (It’s really tasty!). She smiles, I smile.

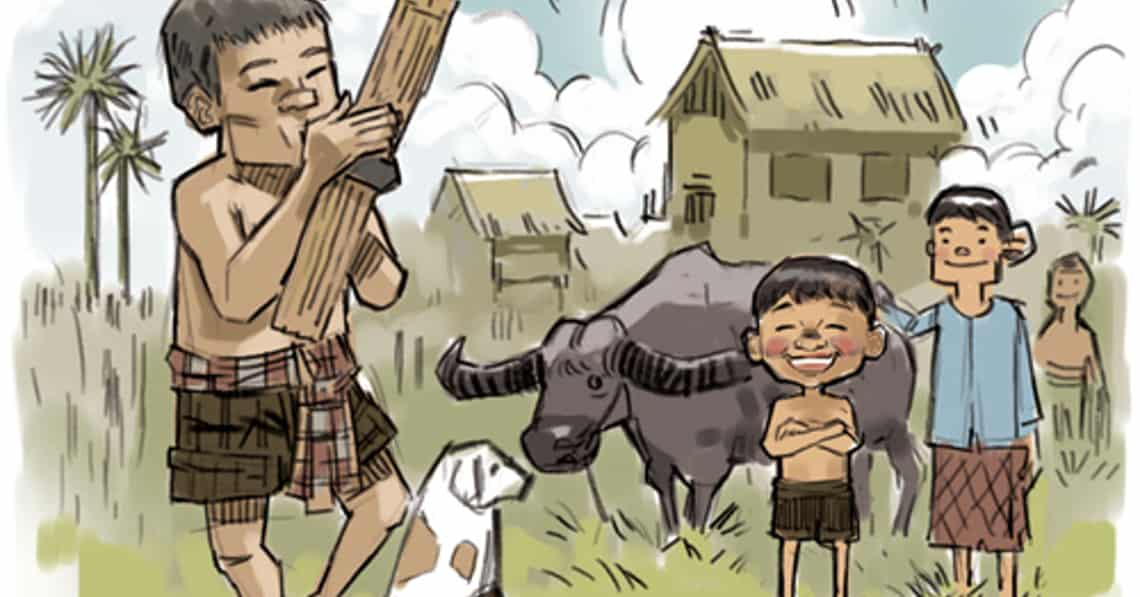

In my mind, this is such an Isaan moment, a term my friends and I came up with to describe the moments in our everyday lives as English teachers in the Isaan region of Thailand that seem to perfectly encapsulate the culture and its people. Because though the people of Isaan share many characteristics with their brothers and sisters to the North and South of Thailand (strong affinity for family, the love of a good selfie, penchant for Hollywood action films), Isaan culture is decidedly independent in many ways from the culture of Thailand or even Laos, a country from which Isaan people derive much of their language (pasa Isaan or simply pasa Laos) and history.

To understand Isaan, we need to start by understanding its geography. Bordered to the North by the Mekong River (Laos) and to the Southeast by Cambodia, Isaan is that chunky, bulbous region that sticks out like a tumour from the narrow strip of Thailand that farang tourists visit, which begins in Chiang Mai to the North and plunges deep to the beaches in the South. Isaan culture, then, is informed as much by Thai culture as it is by Lao culture (in the Isaan villages to the North) and Cambodian culture (in the villages to the East). All of these geographic influences certainly contribute to the sense of identity of Isaan people, but perhaps none of these elements contribute more to what makes Isaan different from the rest of Thailand than the fact that Isaan is a region nearly devoid of tourists. In fact, the few Westerners you find living in the Northeast are either missionaries, young teachers (like myself) or old retired men who moved to Thailand to marry young Thai women, Westerners who contribute virtually nothing to the economy of Isaan simply because they aren’t tourists, but people actually living within these small communities.

This lack of a tourist economy sets Isaan apart from the rest of Thailand because it means that its commerce is almost completely dependent upon agricultural production (namely the production of rice), which means that the region is incredibly poor. So poor, in fact, that thousands of kon Isaan permanently migrate to work in Chiang Mai or Bangkok, sending nearly all of the money they earn (often as construction workers or taxi drivers) back home to the families they’ve had to leave behind. As a teacher working in a large public school outside the city of Kalasin, many of my students live alone with grandparents, having seen their mothers and fathers only a few times in their lives. From my Western perspective, I can’t help but see this as utterly tragic; however, in the small villages of Isaan, this is how life is and how it always has been.

The sense of sabai is strong throughout the Isaan region. In fact, of the many places I have seen and experienced in this country, Isaan is, without a doubt, the most sabai of them all, which might seem odd given its pervasive poverty and oppressive heat. There is no problem that can’t be flicked away with the wave of a thin paper fan and the phrases sabai, sabai and baw pen yang. This pervasive acceptance of “life as it is” seeps into nearly every conversation I have with local villagers, fellow teachers and students alike. They are poor and they know they are poor. Their schools are failing and they know they’re failing. They see the cracks in society, but they rarely talk about change. When I push my coworkers too hard on the subject, many of them offer up the simple statement, What can we do? as a means of letting me know in the nicest, most passive-aggressive Thai way possible that they want the conversation to stop.

And so the conversations do stop, because there is no reason to talk about change that will not come to pass. Nobody’s eye is on Isaan. They receive no attention in news coverage. There is no Citylife equivalent that covers the real, day-to-day issues occurring in Isaan. Over a third of Thailand’s population goes unseen and unheard. In fact, it seems like the only times in which the people of Isaan are talked about at all is when they are collectively referred to as the “rural upcountry” in political debates or speeches, as opposing parties tug at them in contest, trying to convince this large swath of voters that their party and their party alone has their true interests at heart.

As an outsider to this world, it is easy for me to see these things and become frustrated and angry. I am an American and I see massive dropouts in school, poorly controlled water contamination and less than stellar vocational training as things that not only can be fixed, but should be fixed. I come from a country where reform, regardless of whether or not it is implemented successfully, is something that, at the very least, is talked about. When I think about these things and my position as an educator in Isaan, it is easy to feel hopeless. But then I am reminded that my feelings (of anger, frustration, desire for change) showcase my privilege just as readily as does my white skin or my college education. These feelings signify that I have experienced a life different to Isaan and, therefore, can compare and contrast Isaan society with another. But as the old saying goes, trying to stuff Western-perspective-solutions into the belly of Isaan’s problems is like trying to shove a square peg into a round hole – it doesn’t fit, and not because either the hole or the peg are wrong, but because it’s not meant to fit.

Enough with politics. My fellow Isaan teachers would chide me for it, inviting me instead to gin len over plates of som tam laos, kanom jeen, laab, sticky rice and fried bits of pumpkin. Many of our best conversations unfold over the large table in the middle of our school’s administrative office, which teachers pile high with food and kanom. In the small catches of time between classes, we sit, grazing on fried pork and sweet buns filled with black beans. In these moments, as we sit fat with food and gossip, it’s easy to understand why the sabai koolaid tastes so damn sweet and why there is such a desire to overlook the problems that face Isaan society. They are simply too numerous and too heavy, too insurmountable. And even as industry continues to advance and cities like Ubon Ratchathani and Khon Kaen acquire more bus routes and more hotels and restaurants, the economic gap between Isaan and the rest of Thailand continues to be too large to fill with any amount of good progress.

But even in spite of this, life thrives in Isaan. A week before moving from Kalasin to Chiang Mai for the summer, I participated in a graduation ceremony for my M3 and M6 students. Most of the ceremony seemed pretty typical to me: the director read speeches congratulating the students, many of the underclassmen prepared songs and dances. But towards the end, all of the graduating students and many of the teachers kneeled in a circle around this beautifully painted, multi-tiered structure, which almost looked like a miniature wat. A local man from the village began to chant words of unity and good fortune. As he ended, one of the graduating students stood, tying the end of a ball of string to the top of the structure, looping it around his own hands and then passing it along to the student next to him. The string circled around until all of us sat with string in our hands, unified as a community. It was an Isaan tradition that I hesitate to romanticise, but one I feel speaks volumes to the love that Isaan people have for one another and their culture. In spite of what the future might hold for the region, they are a connected people, to one another and to the history and language that they share.