Ryan Libre is a gentle, calming presence with blue eyes and a soft voice. A bee lands on his lap and stays there for the duration of our interview and he just lets it hang out. That’s how calm and gentle we’re talking here. He’s also the founder and director of the wildly popular Documentary Arts Asia (DAA), and one of the hardest-working expats in Chiang Mai.

Twelve years ago, after dropping out of college in California, Libre, an avid outdoorsman, came to Thailand to do some WWOOFing (Worldwide Opportunities on Organic Farms, a non-profit organisation that allows volunteers to live and work in exchange for room and board on farms across the globe) in Isaan. There, he met the influential Jon Jondai, founder of the Pun Pun Centre for Self Reliance. At the time, Jon was just preparing to move to Chiang Mai where he would establish Pun Pun for the first time. Libre went with him.

“I can’t take credit for Pun Pun’s start but physically, I was there,” says Libre with a smile. Two weeks later he returned to the States to finish classes and officially graduate college, and from there moved to Japan, where he spent four years doing landscape and wildlife photography in the country’s largest national park.

“Japan has this 100-plus year photographic history that’s just completely unknown by the western world,” he says. While living in Japan, Libre returned to Thailand regularly before eventually relocating here for good. But he missed the photography scene of Japan.

“I craved that culture of constant gallery openings and new projects going on,” he recalls. Meanwhile, “there were only two photo galleries in Thailand, and both were in Bangkok, about two blocks away from each other. So, I decided to start something, and that something was DAA.”

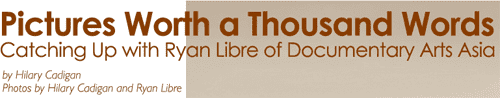

That was six years ago. Libre began by laying groundwork, and four years later opened the physical DAA centre with his Thai wife Non (DAA’s Assistant Director) here in Chiang Mai. Since then, they’ve organised an annual documentary photography and film festival, more than 300 movie screenings, 100 workshops and dozens of exhibitions. Most of their funding comes from Chiang Mai workshop fees, donations, print sales, alcohol sales (people buy more alcohol than art, notes Libre), and volunteer labour (everyone at DAA works for free). They get some grants, but nothing too big or consistent, therefore relying mostly on their reputation for quality workshops and events that people are willing to pay for. All money made goes back into the project, allowing DAA to offer scholarships, gear loans, grants and a residency programme for emerging and under-represented photographers throughout Asia. And last fall, they were able to open a second DAA centre in Laiza, Kachin State, Burma where they train youth from the KIO (Kachin Independence Organisation) area.

“A big part of DAA is the ongoing nature of the project,” says Libre. “For students, a one-time workshop doesn’t do much. Some places give out cameras but then there’s no follow-up. So it’s like, ‘okay, I took a good picture, now what?'”

According to Libre, the key is training students what to do next: how to submit to newspapers, how to exhibit in a gallery, etc. And that’s what DAA does.

“One of our biggest success stories is Hkun Li from Kachin State,” says Libre. “He was a star student in one of our first workshops. He went from never having picked up a camera to doing exhibits in prestigious galleries throughout the region, and now teaches workshops at our centre in Kachin and has a book coming out this year.”

Today, while Hkun Li teaches beginner and advanced workshops to students in Laiza, and two local managers run daily operations, Libre still returns regularly to do teacher trainings and advanced workshops. Simultaneously, for the past six years, he has been filming a documentary about the people of Kachin State.

“I consider myself primarily a still photographer, but when I was setting up lighting and preparing for shoots in Kachin, my camera had a video setting so I thought, I’ll push the record button and see what happens,” says Libre of the project’s beginnings. “Some of the footage ended up being really powerful. The one thing that most impresses me with film is that the subjects are speaking for themselves, so it removes me one more step, which I like.”

In Kachin State, life is not easy. Since the re-emergence of conflict between the Burmese Army and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) broke out in June of 2011 as a result of the central government’s attempts to take over KIA areas, violence has become a near daily occurrence.

“It’s a very serious situation that’s not being looked at closely,” says Libre, noting that for the first four years he was there, there was no fighting, and no foreign presence to speak of. “I first found out about the community from a Kachin student I met here in Chiang Mai,” he adds. “When I looked them up on the BBC website, I got an ‘error, not found’ message. On the New York Times site there were a few obscure references, but that was it. When I first went there, I was one of the first journalists. Then once the fighting and bloodshed started, the others flocked in.”

Libre has been back to Burma over 20 times over the last six years, in the process not only compiling dozens of hours of footage, but also developing indelible ties with the Kachin community.

“My goal is just to create a portrait of the autonomous areas, which definitely includes soldiers and politics, but also just children going to school, learning a language that is illegal in the rest of Burma, and shopkeepers who are rebels just for being there,” says Libre. “Why did they choose to set up here? What is it like? That’s what I want to convey.”

Of course, simply entering Kachin State, one of Burma’s many restricted zones, is a significant challenge.

“To get into Kachin State you don’t deal with the Burmese,” Libre says, “and you can’t get there through Burma. Kachin State has their own border guys who will stamp you in, but first you have to find ways to get around the Chinese. Every time I have to find different ways to not get caught. About two or three people do each year, but I’ve been lucky.”

His potentially unparalleled access to Kachin has given Libre a unique insider’s perspective on the local situation, one that many foreigners lack (including the aforementioned flocks of short-term journalists, whom he says have caused locals to become quite a bit more distrustful of foreigners than they were when he first arrived six years ago). Libre can see clearly what’s happening in these areas, and what’s at stake.

“These people are not actually fighting anything – they’re just claiming their autonomy,” he adds. “But without soldiers on the frontlines, the Burmese army comes in and the whole infrastructure collapses. The schools, the hospitals, they all shut down.”

Right now, says Libre with obvious admiration, Kachin State has a better functioning government, more development, and better organisation than most areas in the region: “There’s free healthcare and a public golf course – just one dollar per game! Kachin had 24-hour power build by rebels before Rangoon did. Today, the Burmese government buys electrical power from the rebels. People going there for the first time are surprised at how advanced it is.”

However, he notes, the violence is starting to affect the community. “I’ll go back and have a drink or a meal with friends, and I’ll ask, ‘Where’s so-and-so?’ And the reply will be, ‘He’s dead.’ It’s gotten to the point where I’m afraid to ask about anyone who’s not at the table.”

Of course, the violence also has affected Libre’s ability to film what’s going on. One of the more novel methods he used during filming was to attach GoPro cameras to guns of KIA soldiers on the frontlines. The results were mixed, and at times tragic: “Lots of cameras disappeared, and one even went to the grave with a friend who was killed while using it. We never got the footage back.”

Over the six years of filming, many different individuals have emerged, and Libre has let the storyline evolve quite organically. But he has already identified two key narrators. One is a cultural historian in the area who is also a “reverend with a lot to say.” The other is “a sweet old schoolteacher with a very low profile” who, in the late 1950s, taught and became a headmaster at a school in Kachin State. Then, in 1961 when the government centralised everything for the first time, changing everything to Burmese and effectively making it illegal for students to learn in their own languages anymore, “that radicalised him.” The schoolteacher joined the KIO as an administrator and eventually rose up the ranks for his good ideas and leadership skills. Adds Libre: “He’s never picked up a gun, but he’s in many ways the leader of the whole revolution.”

Today, the documentary is in the hands of two talented full-time DAA volunteers, who are in the process of editing down the hours and hours of footage. Libre hopes that the finished product will come out by the end of this year.

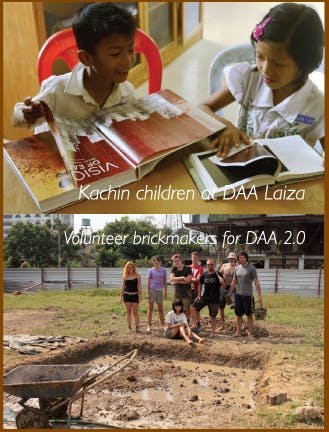

In the meantime, Libre, his wife Non, and a fluctuating team of DAA volunteers have been cooking up a number of other projects. Perhaps the most noteworthy is the new DAA centre in Chiang Mai, which they’re currently constructing – brick by handmade adobe brick – in a privately-owned green space not far from the airport.

The new DAA, which is rather ambitiously slated for completion this year as well, will be bigger, greener, more interactive, more comfortable and more sustainable than the current centre, which is located in a small building off Wulai Road. DAA 2.0’s blueprint includes a large space for public film screenings and workshops, housing for resident artists and volunteers, and possibly even a rock climbing wall. There will also be a brand new Pun Pun centre onsite with a restaurant, farmer’s market and organic garden.

“It’s cool because now it’s kind of coming full circle for me,” says Libre, whose home in Mae Taeng happens to be located just next door to the original Pun Pun. “[Pun Pun founder] Jon was the reason I moved from Isaan to Chiang Mai 11 years ago. Now DAA will have a green space and Pun Pun will move to the city.”

But that’s still not all. Last month, Libre co-produced Chiang Mai’s first ever f28 Month of Photography, a successful assemblage of over 40 photography exhibits all over the city. Simultaneously, he teamed up with Hollywood director Cord Keller and Chiang Mai based producer Chris Lowenstein to start a travelling film school called FilmCoup, providing workshops for students from under-represented communities all over Asia. Oh, and did I mention he also teaches regularly at the photography department of Chiang Mai University?

The bee is still squatting contentedly on Libre’s pant leg as our conversation draws to a close and I ask him, rather disbelieving, where he finds the time to do all of this.

“Well, I have no social life,” he replies.

For more information, film screenings and workshop schedules, visit www.doc-arts.asia

To donate to DAA’s Indiegogo campaign, click here.