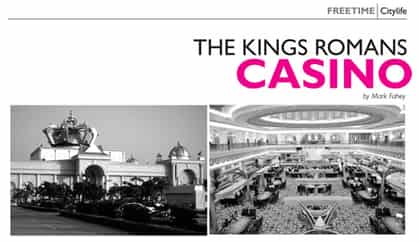

We finally made it across the river about half an hour before the crossing was supposed to close, and only by invoking the name of a contact in far away Bangkok. We were dropped off at the speedboat pier and driven to one of several hotel buildings, which together can accommodate up to five hundred guests. At night, the bars and hotel buildings shine with collections of coloured bulbs, complementing the large multi-coloured crown that tops the dome of the casino building itself. The flashiness of the casino is a big change from the old nighttime scene in the area. As the manager who accompanied us said, “before there was nothing in Laos; there were no lights at night.”

Construction of the pompous sounding Kings Romans started four years ago with a price tag of about 500 million US dollars, including the installation of a 46 km road from the casino to the Laos town of Huay Xai further down the Mekong River (opposite Chiang Khong on the Thai side). According to the manager, there were plenty of challenges, as labourers and materials for the building had to be transported from China into the relatively undeveloped region. The casino is one of several projects located in an area in northern Laos called the Special Economic Zone, to which the government has granted Chinese companies development rights with a 99-year lease. The Kings Romans Group controls 10,000 hectares of that region. At the end of that period, all of the Chinese-owned properties in the area will be turned over to the Laos authorities.

Meanwhile, the casino claims they are seeing about ten thousand guests per month, with many from China, Thailand, Europe, and the United States. However, during our visit we appeared to be the only foreigners in sight, certainly quite daunting at times. It is said to be similar to the casinos found in China’s Macau special administrative region (gambling is illegal in the rest of China). Although the identities of the group’s funders are not public, we were told the group has substantial experience in casino management, including connections in Macau, Burma’s Mongla gambling region, and Boten on the China-Laos border. The manager pointed out that “there are other casinos in Laos, but they are much smaller and not as good.” The company has its own security force to patrol the area. The emphasis on security hopes to prevent the serious problems (including allegations of violence and kidnapping) which plagued the gambling area at Boten.

The complex does seem rather well controlled. There is no drinking or picture-taking allowed inside the casino, and entrances are guarded by security staff and metal detectors. Unlike the bling and glam of Vegas, gambling is serious business here. Inside, huge amounts of money move around under standard casino video surveillance. A live pianist plays a baby grand on a red velvet stage. The interior design is a fusion of grandiose styles: chunky Renaissance murals, sweeping staircases, and huge chandeliers. We watched in unpaid-intern horror as one man blithely bet 625 baht over and over again at a slot machine and another played with a stack of 10,000 yuan card chips. Everywhere there are servers offering water, tea, and coffee, and smoking is allowed indoors.

The massive complex is supported by a staff of 4-5 thousand people, many of whom live in large dorm-like apartments a little outside of the main area. Some of the staff are from the seven villages in the area, and some commute to work by motorbike. Others have come to work in the area from Thailand, Russia, and Nepal. The casino’s management hopes that the project will benefit local people by providing jobs and opportunities for founding small businesses. Already, the manager told us, the area has improved vastly: “before it was an opium and drug businesses, maybe an only ten years before…there were no roads, no electricity, no water…Laos is developing and it is good for them.”

The manager showed us a new village the company built for locals (called Ban Kong), a set of 120 modern buildings, large and identical and yellow, built on stilts. Construction on the complex is slated to continue indefinitely. The group is looking for more partners, and plans on putting in a golf course, a museum, more 4-star hotels, and an airport. They hope to develop a network of branches and agents in nearby cities, including Chiang Rai and Chiang Mai. “In twenty years, we’re planning on building a city here,” said the manager, “This is only a start.”