Finishing one’s first meditation retreat at a Buddhist monastery in Thailand is a ritual unto itself. When I wake up that last day at 4 o’clock, I am excited that today will be the first day practicing what had been preached, and my bag is packed with a certain detached deliberateness. Leaving my simple bamboo bungalow one last time, I walk down to the Dharma Hall as I had done every day for the last 10 days while stopping to feed my friends, the koi, one of those big beautiful yellow flowers they love to eat. I sit alone and have my last vegan breakfast and say my silent goodbyes to the monks and nuns. Then I walk out of the beautiful monastery archway flushed with thankfulness and greet my steed, a 155cc Yamaha NMax, and strap on the luggage. Even after lying idle all this time, it starts immediately, and I begin my drive back to Chiang Mai.

About riding motorcycles: I’ve been an avid and dare I say, mindful, driver all my life.

I own two 800cc bikes back home and honest-to-Buddha, every time I get on something with two wheels and a motor, I am conscious of the danger. Chris Hadfield, the Canadian astronaut who played the guitar and sang Bowie’s Space Odyssey while on the International Space Station, once described an essential part of astronaut training where they are taught to think “What is the next thing that could kill me?”. I’ve adopted this as a lesson in motorcycle driving and have practiced it religiously for years, letting the words run through my mind like a mantra every time I start to drive.

So I pull away from the monastery with my skill as a motorcyclist, not to mention 10 days of mantras and pent-up mindfulness just waiting to be exercised. I start off purposefully slow down the approach road, taking a couple of deep conscious breaths with a silent “Bhuuu” on the inhale and “Dhooo” on the exhale. As I turn onto the main road to Chiang Mai, I notice the beautiful morning sun turned hazy orange through the smoke from local crop-burnings. I think to myself how lucky I am to be cruising homeward on this world-famous mountainous route with supposedly over 1000 curves to carve.

After a glorious two hours’ drive over the first mountain and stopping for petrol in Pai, the sun disappears as I begin the final and largest climb. A little further I am surprised to enter thick fog banks, and mist gathers on my visor. I see the asphalt has darkened with moisture. My inner-Hadfield reminds me these roads are notoriously slippery when wet, so I reduce my speed so that a) I am no longer carving turns that exert a strong outward centrifugal force, and b) I have less need for braking – the two main factors that can cause the tires to lose grip and launch you into a slide.

All goes well up the mountain, but coming down the other side I am aware that there’s an added risk: My upward speed was kept slow with less throttle but going downward, pulled by gravity, I now have to apply more brakes. I stay in my mindful flow and I am not worried.

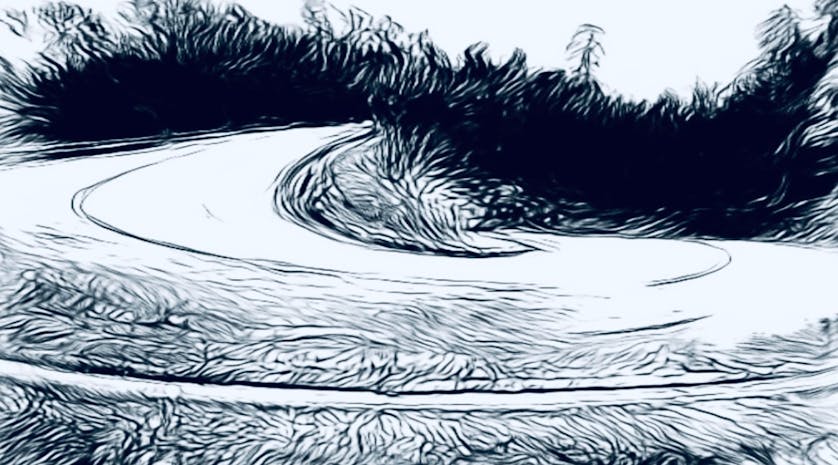

After a few minutes I approach a severe hairpin turn down and to the left. One thing: in Thailand one drives on the left side of the road, and as any bicyclist who’s had to pedal themselves up a mountain can tell you, the angle on the inside of a sharp turn is much steeper than that on the outside. On this particular turn this means the more I stay to the left, the sharper the angle, the more braking is needed, the greater the risk of a slide. Normally, with a good view of an empty road ahead, you can move right – into the oncoming lane – and use the lesser angle to ease the turn.

But that’s not possible because two trucks are coming in the upward direction; big all-purpose freight trucks with double rear axles and double wheels. I can even hear through my helmet the first truck labouring uphill as we approach the turn at the same time. My front wheel drops down at the crux of the hairpin as I ever-so-carefully apply the brakes while aware that I’m in a critical zone – if anything happens, I will certainly slide into the truck’s path… And somewhere within that awareness, I surreally feel my rear wheel slip out and forward so that the scooter flops onto its left side with me still on top it as it skids, tires first, down into the oncoming lane and toward the first truck, maybe 15 meters away. My momentum is set and there’s nothing I can do. Rather than a sense of horror or impending tragedy, I feel a certain awe and wonder at both the immediacy and the unlikeliness of the situation.

As I skid, it becomes apparent that I’m not going in front, or under the bed of the truck but rather directly toward the rear wheels. I’m paralyzed and take no action – there’s no time for evasive manoeuvres other than to brace for impact. The scooter’s downward facing tires violently hit the forward rear tires of the truck, and the scooter and I ricochet off, spinning and sliding down the centre of the road until I stop.

There is silence. Both trucks have stopped. The driver of the first truck is running toward me eyes wide and mouth open like he’s seeing a ghost. I stand up dizzy from the spin, and feeling an extreme shot of adrenaline, look intensely at the driver while putting put my hands over my heart and blurting “OK! I’m OK! I’m OK!” He’s yelling something at me in Thai and I turn away and walk back to the scooter. I pick it up as if it had no weight and get back on. I’m surprised when it starts up, and without intending to leave the scene of an accident, I very slowly drive away down the road while fixating on the questions, “Is the scooter ok? The chassis? The wheels? The brakes?” I test the drivability and it seems to be ok. I continue slowly down the mountain, and feel numb.

After 10 minutes I stop at a roadside coffee bar. As I walk up, the proprietor looks at me with concern and points to blood stains on my shirt. I see a small puncture on my left hand. I dress the wound with a paper towel. Besides that, nothing. No torn clothes or road rash, as I had ridden on top of the scooter as it slid down. I know that I’m in a state of shock, and just sit there looking at my hands tremble while I drink coffee and gather myself for half an hour or so. Before leaving, I inspect the scooter and find the damage is minimal. Just a few scrape marks on the side of the centre stand that it had skidded upon. The body, remarkably, is unscratched. Mechanically, it’s perfect.

During the 90-minute ride back, the incident plays on a continuous loop in my mind. I’m hyper-aware and feel little or no emotion. It is surreal to arrive in the familiar surroundings of my guest house in Chiang Mai. As I climb the stairs to my room, I think of the film “The Sixth Sense” and the surprise ending where Bruce Willis realises that he’s dead and his spirit is only imagining being alive. I walk into my room and start to cry for no reason.

I hardly sleep that night, the mental loop rerunning frame by frame. The road seemed too steep for it to be loose gravel. Probably a few drops of oil fallen on the road from a leaky crankcase or something. How exactly did I make contact so that I bounced instead of went under the wheels? I imagine the alternative fatal outcomes in morbid slow motion and keep coming back to the bizarre feeling that both me and the motorbike barely have a scrape.

The next morning after sunrise my internal clock tells me they are meditating back at the monastery. I sit on my yoga mat on the floor of my room and breathe a silent “Bhuuu” on the inhale and “Dhooo” on the exhale, but soon stop because I can’t yet take a mindful distance from my thoughts. So I head out for my ritual morning coffee, get back on my Yamaha, and ask myself, “What is the next thing that could kill me?”