It’s a moonless night in Amphawa as we rush toward the Mae Klong through a bustling market, tightly packed carts selling steamed mackerel and skewered razor clams, crowded shops hawking sunglasses and t-shirts. We’re looking for a guy named Yut, otherwise known as Teerayud Atiroj, founder and proprietor of one of Amphawa’s first firefly tours.

It all started 20 years ago, when Amphawa’s municipal mayor hired local boat merchants for 500 baht a day cash to sell various goods, hoping to develop the once small village into a lively market and tourist site for visiting Bangkokians.

Today, Amphawa is the only floating night market left in Thailand, attracting thousands of people every weekend from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Open vessels crowd the klong, barbequing fresh seafood and selling straight from the boat as tourists take photos from the bridge. It’s the pulsing heart of a sleepy town full of criss-crossing waterways, friendly villagers and coconut palms.

Yut established his Mae Klong River Tour in 2004, one of four tour companies that opened that year, spearheading a trend that has now grown to over 20 different businesses. The attraction? A rare species of fireflies (pteroptyx malaccae) that flash in unison, blinking together like a silent orchestra.

How do they flash in sync? The long answer is complicated and not fully understood, delving deep into the intricacies of pheromones and the very nature of synchronicity itself. Mathematician Steven Strogatz has an interesting TED Talk on the subject. Why do they flash in sync? That’s a little easier, though it was only very recently discovered. Male fireflies sync in order to convey one simple message. In Strogatz’s words, that message is: “Come hither. Mate with me.”

These synchronous fireflies are found in only a few places around the world (mostly in Southeast Asia) but are plentiful here in Amphawa. No one – not even leading firefly experts – knows exactly why the fireflies gather here, making their homes in the mangrove trees (known locally as lampu) that line the salty Mae Klong. But that hasn’t stopped business-minded locals like Yut from turning the phenomenon into a profit-maker. Today, Yut himself owns 18 boats, packing up to two dozen people on each one for 60 baht a head. (Other companies, which can be booked on the internet, charge as much as 5,200 baht for private tours that include dinner and transportation from Bangkok.) Each of Yut’s boats makes two to three trips a night, from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. We’re aiming to make it to the 7.10 tour as we amble toward the river, searching blindly for someone who looks like they’re about to show us some fireflies.

Then suddenly there he is: a smiling middle-aged man with ear-length hair parted down the middle and a short-sleeved button-down, poised beside the river with a bullhorn. His best friend and business partner, Noi, sells noodles at the closest shop, where four crazed little dogs (one named Batman, one named Snow) fight for attention and food scraps. The boat, a technicoloured long-tail painted with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs cartoons, is nearly full, its passengers decked out in bright orange life jackets. We clamber on with grumbling stomachs, having meant to eat before the tour began, but unfortunately it’s already 7.08.

“You hungry?” Yut asks. “Order food here. No problem!”

The next boat over is serving hoy tod, freshly fried mussels with egg and bean sprouts and Sriracha sauce. We are handed three steaming plates on a pink plastic tray with ice cold Leos as we settle into our seats. Life is good.

The engine roars in our ears as our driver, who also happens to be named Yut, manoeuvres through the cool night air. We putter past rows of lighted homestays and restaurants lining the klong before reaching a darker area. It’s only then that we notice, slowly at first, that some of the trees are full of tiny points of light, blinking like Christmas in the blackened sky.

The driver cuts the engine, mercifully, and we float, basking in momentary silence. Some of the trees are bursting with light; we wonder if they’re fake (Other Yut says that’s the most common question he gets) until we notice some of them flying around. These are no LEDs.

“They live only 49 days, and fly for 15,” Other Yut tells us.

Bats with one metre wingspans swoop down all around, feeding on fruit and other insects, but not the fireflies; their lights act as a deterrent. Some of our fellow passengers try to take photos but it’s hopeless, like trying to photograph stars with a point-and-shoot. As I gaze at the little lightning bugs, clinging to their leaves and flashing in unison, I feel a shiver down my spine, the sensation of coming into contact something that feels a little like magic. I’m brought back to my childhood, where we used to spend entire summers chasing fireflies in the backyard, catching them in jars with holes in the lids, spending the night with the glow of captured moonlight at our bedsides before setting them free the following evening. I’ve wondered ever since, what happened to those guys? I never see them around much anymore.

And it’s true; the fireflies are dwindling, not just in America but here in Thailand, and everywhere. While there are still fireflies in Amphawa year-round (their numbers highest during the rainy season) residents report a marked decrease over the past generation. The sparse patches of flickering fairy lights are magical to me, but apparently nothing compared to the bright swarms that used to light up the night, so much so that fishermen could navigate the river electricity-free.

No one knows exactly why fireflies are disappearing, but scientists point to land development and light pollution as two of the most likely culprits. Development, obviously, depletes the fireflies’ habitats, while light pollution impedes their ability to communicate. Remember, fireflies speak to one another with light – males blink to attract females so they can mate – meaning the excess of artificial light that now illuminates our world spells disaster for fireflies.

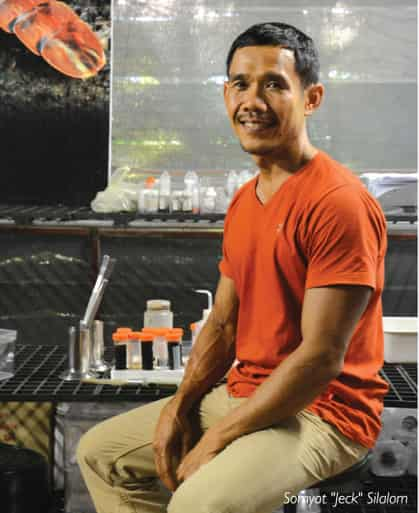

“Imagine if we humans were trying to have a conversation in front of a loud speaker.” I’m back in Chiang Mai now, at the Queen Sirikit Botanical Gardens, speaking with Dr. Somyot “Jeck” Silalom, one of Thailand’s leading firefly researchers. “That’s what artificial light is like for fireflies,” he says.

With a bright smile and an athletic build, Jeck looks quite young for someone in his mid-50s, and has an infectious enthusiasm for all things firefly. He came to Chiang Mai from Ubon Ratchathani nearly three decades ago to study environmental science at Chiang Mai University, and has been here ever since, developing his studies of water quality into the mysterious field of fireflies. His work at the Botanical Gardens is part of a larger ongoing research project partnered with Kasetsart University in Bangkok.

“Twelve years ago, the Queen came here and saw the fireflies,” Jeck recalls. “She asked, ‘What is the relationship between fireflies and trees?’ No one could tell her. That is the origin of this project.”

Jeck is part of the project’s third generation, which he has been involved with for nearly five years now. The first generation was dedicated to studying firefly origins, with the goal of identifying how many species exist here in Thailand. Their final approximation was over 100, which accounts for over five percent of the world’s firefly species (indeed, of all the continents, Asia has more fireflies than anywhere else). The second generation focused on breeding and how to increase fireflies’ dwindling numbers. Now, Jeck’s job is to study the fireflies’ biology and ecology, a subject that remains strangely shrouded in mystery for scientists worldwide.

In fact, scientists still aren’t even sure what fireflies eat.

“There’s a lot we don’t know,” says Jeck. See, here’s the thing: fireflies are only technically fireflies for about a quarter of their short lifespans. Most of the time they spend as wingless larvae, during which they live on or under the ground and typically feed on insects, snails and worms. Adult fireflies may also live on other insects, as well as pollen and plants, but it’s possible that some species don’t eat anything at all, since their lifespan is so short. So why are they attracted to certain trees (like the lampu in Amphawa)? It’s still a mystery.

“We do know that fireflies are predators and carnivores. They get quite aggressive when they’re hungry and may even bite humans,” adds Jeck with a jovial grin. “They’ll also eat their friends!”

The Giant Fireflies (lamprigera tenebrosus) that Jeck studies, which are the largest species in Thailand, can grow up to 10 centimetres long – that is, if they’re female. “The females are 10 times bigger than the males,” notes Jeck. “You know why? Think about it. Big burden!” Female Giant Fireflies are wingless, lay about 60-70 eggs at a time and carry them for two months until they hatch. Then they die. One mom, one batch of eggs; another generation extinguished, another brought forth.

We walk into Jeck’s firefly nursery, a screened-in room with a thatched roof, surrounded by bamboo trees and a green Valley beyond. Jeck opens a clear plastic box to reveal a giant, fat glowing mama, curled around a nest of perfectly round eggs, the size of match heads and green as glowsticks. It reminds me of a slightly creepy toy I adored when I was younger, the snuggly, light-up Glo Worm doll.

There are dozens of other boxes throughout the room, identical yet empty, save for a layer of soil and a piece of wood. Jeck looks down. “I had 2,000 fireflies a few months ago, but they contracted an infection, a communicable disease that spread quite fast, and within a few weeks almost all died,” he says softly. “I panicked. It was so sad.”

The loss is a reminder of the fragility of fireflies. We have grown up with them, sewn them into our cultures, our mythologies and our imaginations, and yet we know so little about them. And like so many other species on our planet, their very existence is threatened by ours, by our insatiable appetite for progress.

Which brings us back to Amphawa, a town that has been profiting off its fireflies for a decade now. “The synchronous flashing of pteroptyx malaccae on trees along the Mae Klong riverbank is spectacular and fascinating,” wrote Anchana Thancharoen, Jeck’s project advisor at Kasetsart University, in a recent paper for The Journal of Bioluminescent Beetle Research. “However, firefly tourism at Amphawa has brought many problems to the local community and also to the firefly population. It provides a case study of how poorly planned tourism can destroy the very thing that attracted tourists.”

Indeed, despite my affinity for the Yuts, and for the entire experience, Amphawa is not a prime example of eco-tourism done right. The lights and the development have disrupted the fireflies’ environment, and the noise of the tour boats late at night has created such a disturbance for local residents that some have actually cut down the precious lampu trees in front of their houses, just to rid the area of the fireflies that bring tourists.

“The problem is that tourists have flooded into the area at a rapid rate and we were not well prepared for it,” Surajit Chirawate, president of Samut Songkhram’s Chamber of Commerce, told The Nation newspaper in 2007. “We encouraged tourists without being prepared for the consequences.”

But that doesn’t mean the magic of the fireflies is something we should avoid. As Anchana notes in her paper, well-managed firefly tourism could actually be the key to conservation, and her team at Kasetsart University strive to bring an element of education to the mix. Their service projects including training locals in firefly biology, which they can then share with tourists, providing handbooks as a community knowledge resource, and putting up educational signboards for tourists at the piers.

“Recently, interest in firefly conservation in Thailand has spread beyond tourism areas,” Anchana wrote. “Fireflies are becoming recognised and appreciated as a national treasure of this country.”

This year, Jeck has a whole new batch of firefly larvae, about 50 in all. So far, no diseases. Meanwhile, his field research around the mountains of Mae Rim has turned up some exciting finds, including a firefly species that is either the first of its kind found in Thailand, or a brand new species altogether.

“Amphawa is one example of a firefly watching spot, but it’s not the only one,” says Jeck. He recalls one of his best memories, camping deep in the woods of Nam Nao National Park in Phetchabun, the only time in his life when he saw thousands of fireflies together in the wild. “When I flashed my flashlight at them, they suddenly synchronised. It was…” his voice cracks a bit. “It was just…WOW!”