For as long as I remember, Bhutan was on my bucket list. I didn’t know much about Druk Yul, or Land of the Dragon as the Bhutanese call it, but it beckoned. And like every Thai person (read woman), King Jigme’s exotically suave looks (he made Vanity Fair’s International Best Dressed list this year, didn’tjaknow) did nothing to dim the draw I felt towards this reclusive Himalayan kingdom.

A quick read of the Lonely Planet on one of the two airlines which actually fly into the country, Druk Air, told me that Bhutan is a kingdom of 700,000 people and is only double the size of Chiang Mai province at around 40,000 square kilometres. It is among the most reclusive nations on earth, only having slowly opened up to the outside world since the seventies (it joined the United Nations in 1971), and through tight control, attracts a mere 120,000 tourists per year. It is also, amazingly, carbon neutral, its ecosystem being lauded for its biodiversity and its government enforcing strict rules and regulations to protect its environment, a whopping 72% of which is covered by forest.

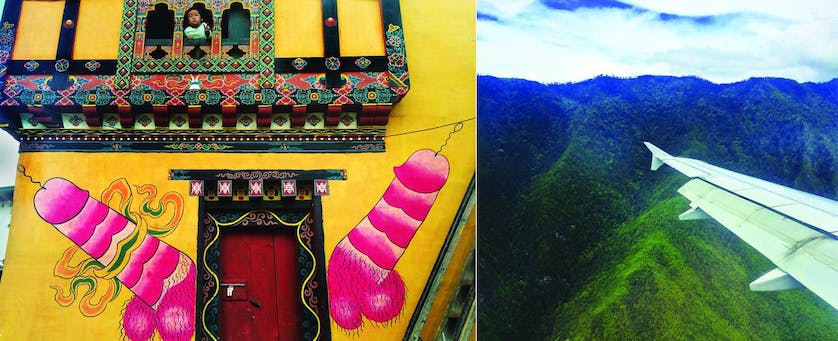

But soon Lonely Planet was turned into a big rosary bead as we descended towards Paro, the country’s only international airport. As the captain performed a giant slalom between mountains, which acted as immovable and deathly poles, I gawped at wandering cows looking right at me from their elevated pastures and flinched as the wing appeared about to clip the shingles of a couple of mountain-side homes. You see, until 2011, only eight commercial pilots were certified to fly into this nutter airport (reassuringly named by Travel+Leisure in 2009 as the world’s most dangerous airport), and even now there are only six flights per day arriving in Paro, with a strict no flying after sunset rule.

It was a joyful moment arriving _ alive _ in Paro with its fresh thin air at 2,250 metres, surrounded by towering mountains, some over 6,000 metres high, and with a giant billboard of the handsome Jigme and his beautiful wife Jetsun to greet us. In fact, like our king, the fine features of this royal couple grace every home, shop and town in the kingdom.

It turns out that in one way _ well, the only way _ visiting Bhutan is like going to Club Med. Once you have paid your travel agency your set fee, your flights, accommodation, guide, private car and chauffer, all meals and entry tickets, are covered. Apart from tips, wine and souvenirs, there is no reason to ever spend another ngultrum during your stay. From the minute our cute guide, Tandin and our dapper chauffeur Kingka, picked us up at the airport, my small group of friends and I were treated to a custom tour of the country. We were looking for beauty, for culture, for cuisine, for adventure and for fun and our new Bhutanese friends delivered with aplomb.

Within half an hour of being in Bhutan, we were grateful for our motion sickness pills after each of us began to turn a different shade of green wending our way towards the capital, Thimpu. Apparently, after China swallowed up Tibet, Bhutan did the sensible thing and got into bed with its other neighbouring superpower, India, who, with its own ulterior motive, offered to build the country’s road system. The cunning Indians, wary of gobbling China, continue today to export labourers from Nepal and India to expand and maintain the country’s roads which now stretch to 8,000 kilometres of terrifying beauty. Not wanting to give China any excuse to wander south, India had deliberately built what must surely be the world’s most winding and least direct roads (averaging a stomach turning 10 bends per kilometre _ take that Pai!), lazily meandering along (and clinging to) steep mountain sides _ any troops heading to India’s borders would be performing a new version of the Long March.

As we drove past vast family homes featuring wooden pine beams and painted in colourfully fancy designs (by law every building must incorporate traditional designs), giant whitewashed mountain top dzongs which act as both monastery and local administrative offices, and quaint villages where the majority of people still wear their traditional costumes (the men’s wear, goh, is impressively dashing when worn with knee-high socks), it was becoming obvious that while time had not stood still in this Shangri-la, it was moving at a different, and much more cautious, pace.

While religion and tradition permeate daily life in Bhutan, it is no longer simply an impoverished Himalayan kingdom clinging to its past. Bhutan’s series of progressive kings have led the charge for change. Abolishing slavery as recently as 1958, coining the intriguing term Gross National Happiness as a national policy in the seventies and abandoning absolute monarchy while calling for electoral democracy in 2008. Education, which is free, has been an integral part of Bhutan’s development starting in the seventies when each household had to send one of its members to study English. All hunting, including fishing, is banned, as is encroachment on forest reserves (it is illegal to cut trees without permission, though sadly Han Chinese poachers and loggers have been sneaking in from the north and doing great damage to the environment). Today, signs of change are prevalent with ubiquitous smartphone use, vast wifi coverage and mainly the young, choosing to wearing jeans rather than gohs, or the female national dress kira. But once you leave the few large towns, it is straight back to nature and tradition.

In spite of Bhutan’s developmental prudence, Thimpu is officially the fastest growing capital in the world, having trebled in size in the past decade to its current population of 100,000. Yet it is like no other capital you have ever been to. Nestled in a valley fed by the crystal clear Thimphu Chuu River, and surrounded by the country’s signature Himalayan peaks dotted with gleaming dzongs, it also has the distinction of being the only capital city which doesn’t have traffic lights. In fact, a few years back one was installed, but was protested away by residents who thought it too ‘westernised’. Today, the busiest intersection is manned by a policeman in a box waving his white-gloved hands at oncoming traffic _ which is, of course, one of the city’s top attractions. Considering there are only 63,000 registered cars in the entire country, there is no immediate fear of another set of lights taking hold.

Thimpu is a good start to the Bhutan experience, we first headed to the Tashichho Dzong, seat of Bhutan’s government since 1952 and home of the throne room and offices of the king…and best of all a short waving distance to King Jigme’s palace (mum actually asked me to say hi, a task I admit to have failed in). We then visited the exquisite textile museum which showcased just some of the fine textiles we were to come upon throughout our journey as well as stopping off at the spotlessly clean market where yak cheeses, slabs of cured meats, piles of chillis and forest vegetables offered clues of the cuisine to be sampled. After a short stop at the General Post Office, where we actually had our own photos taken and used as stamps to impress our loved ones at home (two weeks later, I am still waiting for the postcards to arrive), we headed to our hotel. Throughout our visit we stayed at three star hotels, all very clean, comfortable and, of course, part of the package. Feeling perky, a couple of us decided to go out and explore Thimpu’s nightlife and as we made our way down the city’s dark _ and very safe _ streets, I actually came across a rather sweet Bhutanese punk, hair steepled to the heavens, before ending up in a lounge bar where, for a few ngultrum, a girl would come up and dance for us on stage _ not the hottest of world nightspots. It was good to know though, as before we left the capital the next day, we made sure to stop off at a duty free shop and stocked up on a week’s supply of wines.

Driving in Bhutan is petrifying and breathtaking. Roads tend to only be one and a half lanes wide and with constant landslides, and frequent steep drops of up to a thousand metres, it’s not for the fainthearted. But yet, as many signs dotted along the way warned, “Take your Time”, “Better to Arrive Late than Not at All”, the nation’s drivers are on the whole extremely cautious. As we swayed pliantly in the van (ladies, two words, support bra) stopping frequently for road works (Tandin impressively checking a web site on his iPad which gave up to date information on road closures), we were almost hypnotised by the beauty: dizzying views of glistening and frothy rivers meandering along valley floors, white and gold dzongs blinding in the sunlight one moment and shrouded in thick moist mist the next, we were enveloped by the endless risings and tumblings of the Himalayas as we drove past dozens of waterfalls leaking out of the porous and rain-bloated mountains.

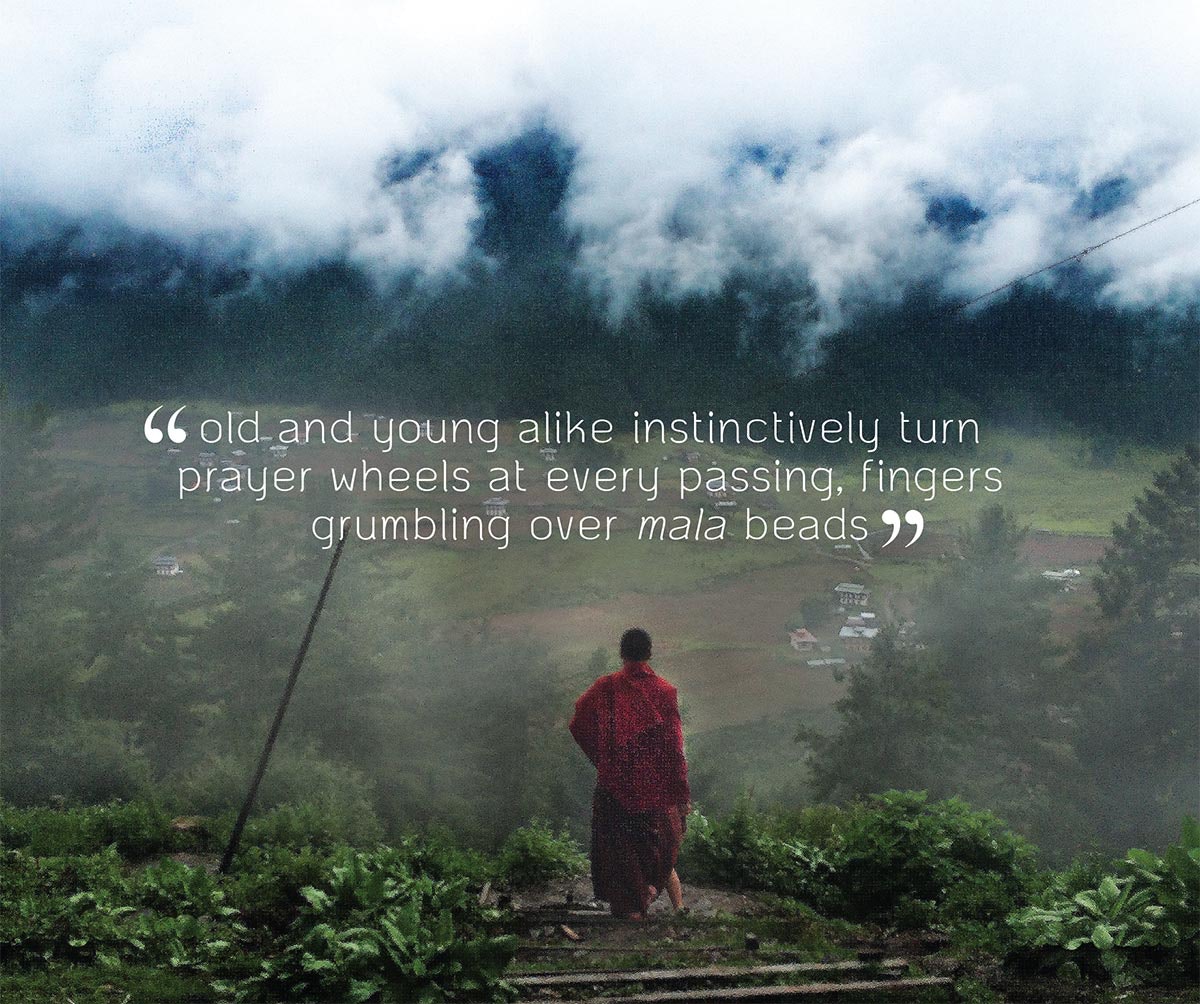

Buddhism is at the heart and soul of Bhutan: colourful prayer flags flutter along mountaintops, occasional giant incense burners waft their saccharine fumes into the wind, water wheels rotate dharma with their constant flow, old and young alike instinctively turn prayer wheels at every passing, fingers grumbling over mala beads: nature and man joining together to whisper prayers across the kingdom. To paraphrase a quote from an old Citylife article on Tibet, like romance in Paris, legend in Egypt and sex in Bangkok, there’s something in Bhutan’s admixture of history, geography and people that can only be characterised as spiritual…it oozes it.

So it came as a shock when, during a gentle hike to Punakha’s Chimi Lhakhang temple, we passed a village where homes were adorned with rather graphic paintings of phalluses. It turns out that a libertine monk in the fifteenth century aptly named the Divine Madman, a practitioner of the Himalayan’s animistic Bon religion, had inspired this symbolism. Different sources tell of different reasons for this nation-wide phallic obsession. Some say it is to ward off gossip and bad luck, others that it is an irreverent take on the worshipping of Buddha images, while Tandin, with tongue in cheek, claimed that it was to promote humility, “should men get too, er, cocky, all they have to do is look at these large penises and become humble.” And that is how I found myself being whacked on the forehead by a golden penis by a monk offering his blessings on a Himalayan hillside.

And it is a quirky country. Driving past mountain roads lined with marijuana plants, I insisted on jumping out of the van to pick some, only to be told that the THC was so negligible that it was only used to feed pigs. According to Tandin, pigs then get the munchies and eat a lot, fattening themselves for slaughter, they are also too stoned to move much, so their meat becomes tender and on top of that, well, what a way to go!

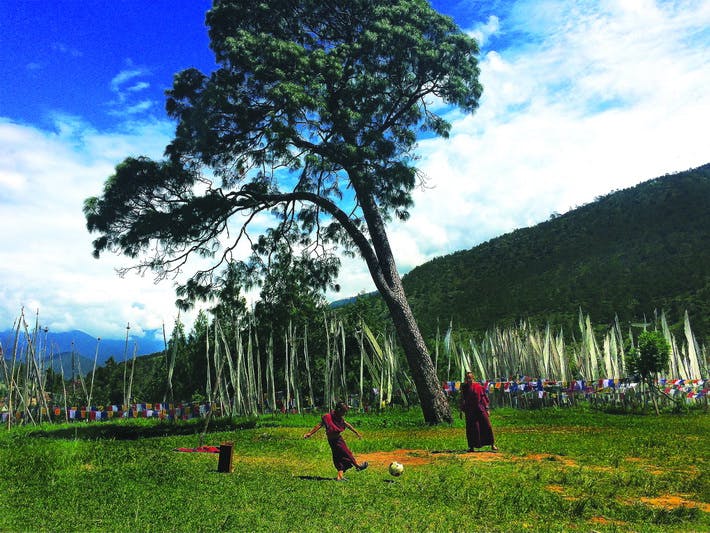

The people are also charmingly eccentric (and really really good looking). Every Sunday on many village greens (typically near a dzong), archers, all of whom must wear their Sunday best gohs (knee-high socks compulsive) come out to enjoy their national sport. Replacing bamboo bows and arrows for US-imported models costing in the thousands of dollars and aiming from distances as far as 140 metres (compared to the, pfft, 50 metres in the Olympics), I could hardly see the archers, let alone the arrows before hearing the thwack of impact. There was good natured smack-talking and even a little victory song and dance every time the target was hit…all fun and games until you find out that archery injuries are among the most common reasons for hospital admissions in Bhutan.

During our week we travelled into the centre of Bhutan as far as Trongsa, a five and a half hours’ drive from Punakha, covering the grand distance of 130 kilometres (or, as we calculated with a collective groan, 60 kms as the crow flew). The morning views from our hotel overlooking the valley towards the mist-shrouded dzong was one of the most breathtaking I have ever experienced. In fact, there were many moments when we simply gazed at each other, faced with yet another heavenly vista, awed by our fortune. Monkeys clinging to tree tops, Spanish moss to pine trees, colourful birds perched on road signs announcing 20 kms an hour speed limits and idyllic looking villages dotted the landscape. We eventually doubled back towards Gangteng Valley where each winter graceful black-necked cranes migrate from Tibet. The cranes are so celebrated and protected that the government has buried all electrical cables in the area in fear of bird mortality. Now that’s conservation.

Though we were happily pleased with our stock of wines, organising picnic lunches by crystal clear rivers and enjoying sunset drinks overlooking the endless vistas, we did struggle a bit with the cuisine which, thankfully for we Thais consisted of a lot of chilli, but also included an excessive amount of cheeses and some rather tough cured meats. Joyfully, we discovered that the Swiss government has been lending a helping hand and there was surprisingly great cheese to be found from time to time. We had ema datsi, the staple dish of chilli and cheese at every meal and even gave the salty yak milk tea a go, but I am afraid to say that food was not gushed over in the postcards home.

Unfortunately, following a frolic in a mountain waterfall, I caught the flu and missed out on the climax of the trip, the three hour trek up to Tiger’s Nest, the spectacular cliff-side dzong which is featured in just about every postcard from Bhutan. My friends all managed the climb and I was forced to jealously hear all about it as I joined them for a traditional hot stone bath afterwards.

As we sat down for dinner with the owner of our tour company (another Tandin) back in Paro, we asked him why he wasn’t on TripAdvisor, as we wanted to give his company a five star rating. His answer was measured, “I do not want to grow without fully thinking of consequences. Like Bhutan, my business is sufficient, but I must think about its impact on my country.”

And there you have it. A country clinging to its identity and ways of life, balancing progress and happiness for its people with the awareness of its position not only between two superpowers, but as a member of the rapidly changing worldscape.

As I looked out of my small aeroplane window, making eye contact at what surely must have been the same cow, it made me sad to think of Thailand and how we have sold ourselves to the highest bidder, carving out slithers of our soul in exchange for hard currency. In comparison to the old madam that is Thailand, Bhutan is like a young girl in full bloom, still treasuring her innocence and taking slow cautious steps into the big bad world.

I will be back.

Highly recommended is Bodhi Dhama Tours, email Tandin at bodhitours@gmail.com or ttshering78@yahoo.com.